Fascinating reason why women are more likely to get addicted to smoking than men, new study reveals

Scientists from the US have made the remarkable discovery that women are more likely to become addicted to cigarette smoking than men.

Intriguingly, researchers at the University of Kentucky found this to be true, despite the fact that there are more male smokers than women in America.

According to the CDC, about 13 in 100 adult men smoke, compared to about 10 in 100 adult women.

The new study has also shed light on why this might be so.

The findings show that estrogen, the female sex hormone, can make a person’s brain more sensitive to the effects of nicotine in cigarettes – and therefore more likely to become addicted.

Supermodel Kate Moss is perhaps one of the world’s most famous female smokers – pictured here modeling for Louis Vuitton during Paris Fashion Week in 2011.

However, research shows that men try to smoke more often, which partly explains why there are more male smokers than women.

“Research shows that women have a greater tendency to develop addiction to nicotine than men and are less successful at quitting,” says Sally Pauss, a doctoral candidate studying molecular biology at the University of Kentucky College of Medicine in Lexington.

Pauss, who led the study, wanted to discover why this gender disparity exists. She presented her research at the annual meeting of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Men have a natural amount estrogen in their bodies. But women produce it at much higher levels, that fluctuate every 28 days during the stages of their menstrual cycle.

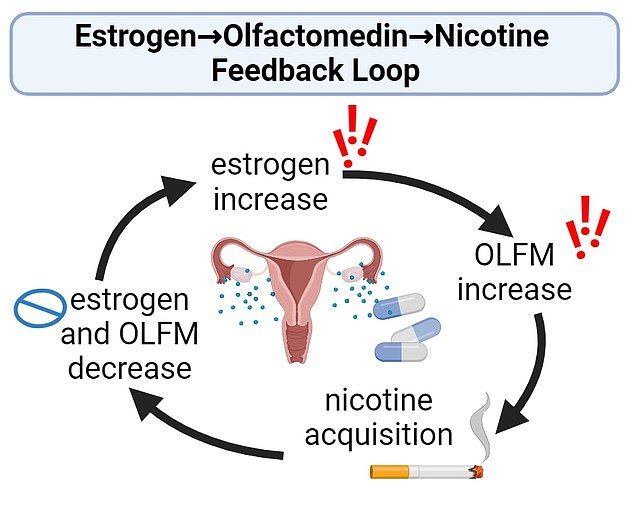

In her new research, Pauss discovered that estrogen increases the effect of proteins important for the brain’s pleasure response to nicotine, called olfactomedins.

Estrogen activates olfactomedins. The proteins then activate the part of the brain associated with addiction and reward, causing a person to crave nicotine.

A diagram from Pauss’ research showing how the course of estrogen and nicotine cravings occurs

Filling the nicotine fix causes a reduction in the amount of olfactomedins – as well as estrogen.

The study found that peaks in estrogen, such as in the run-up to ovulation, lead to an associated increase in olfactomedins.

Pauss and her colleagues identified this protein by scouring vast genetic databases and looking for genes that are both affected by estrogen and control brain chemistry.

They found only one type of gene that met their criteria: the gene that makes olfactomedins.

Once they discovered that gene, they grafted it into lab rats and conducted a series of experiments to find out how estrogen, olfactomedins, and nicotine interacted.

Looking ahead, Pauss said scientists could develop drugs that target these proteins and block their effects, helping people quit.

‘If we can confirm that estrogen stimulates nicotine seeking and consumption through olfactomedins, we can design drugs that can block that effect by targeting the altered pathways.

“These medications would hopefully make it easier for women to quit nicotine,” Pauss said.