Godfather of mRNA vaccines reveals plans to immunize people against CANCER years before tumors strike to ‘prevent the disease from ever appearing’

The pioneer behind mRNA vaccines has unveiled plans for a new vaccine that immunizes against cancer more than a decade before it hits.

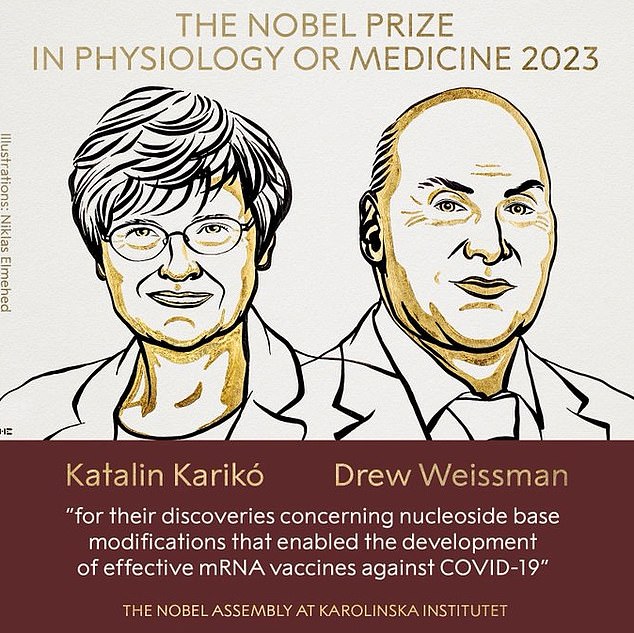

Dr. Drew Weissman won the Nobel Prize this year for their discovery of a way to inject genetic instructions to trigger an immune response against Covid, a discovery that helped save millions of lives and get the world out of the pandemic.

Now he is using this discovery to create an mRNA vaccine against one of the biggest killers in the world: cancer.

The vaccines are being developed at the University of Pennsylvania, where Dr. Weissman's research teaches the body how to recognize and fight tumor cells as they form.

Dr. Drew Weissman, a vaccine researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, has pioneered mRNA vaccine research and won the Nobel Prize for discovering how genetic instructions for mRNA can be delivered into the body to trigger an immune response against Covid to bring.

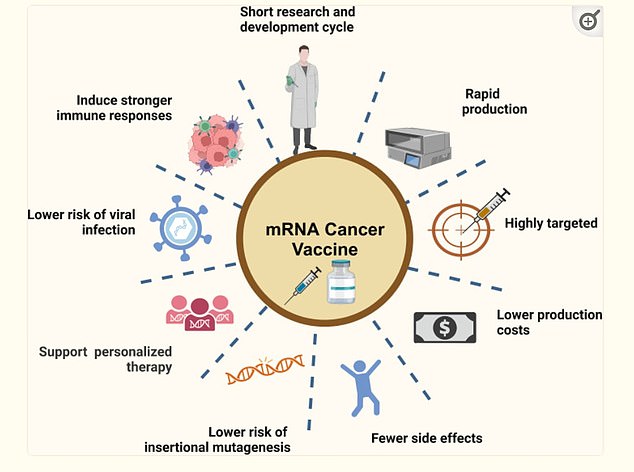

The mRNA platform could easily be coded to target specific cancer types. This is a great advantage because cancers are very specific to each patient and require treatment specifically tailored to him or her

The vaccines are aimed at people with genetic mutations that increase the risk of cancer, such as the BRCA gene that affects breast cancer risk.

Dr. Weissman said during the Nobel Prize lecture on medicine: “The idea here is that you treat people before they get cancer… and maybe completely prevent cancer from ever occurring in these patients.”

Cancers resulting from genetic mutations account for between five and ten percent of the more than 18 million cancer cases in the world each year.

Environmental and lifestyle factors such as smoking, obesity, stress and physical inactivity can also increase the risk of the disease.

Dr. Weissman and fellow UPenn researchers set out to find a way to boost the power of an mRNA vaccine by encoding it with genetic instructions for the body to produce a specific subset of immune cells that kill cancer cells.

Within that set of genetic instructions injected into mice to produce an antibody response, the researchers added mRNA that teaches the body to produce a protein called IL-12, which plays a crucial role as a messenger that facilitates communication between cells.

IL-12 directs the body to generate a specific type of immune cells called effector T cells, which Dr. Weissman said they can effectively remove cancer from the body and even prevent it from occurring in people with the highest genetic risk.

He said: 'We know that it takes five to ten years for cancer cells to first appear before you develop full-blown large tumors that hinder function.

“If we treat these people maybe every five years with a vaccine that makes only effector T cells, we will clean up, clear out and kill all the transformed cells.”

Katalin Karikó (left) and Drew Weissman (right) are credited with helping change the course of the pandemic. Before mRNA jabs were rolled out to millions of people around the world to protect them from Covid, such technology was considered experimental. Researchers are now investigating whether it can help beat cancer and other diseases

The introduction of IL-12 mRNA also increased the activation and range of effector T cells by a factor of 10. They became so widespread that they were found in both the spleen and lymph nodes.

A major advantage of an mRNA platform for Covid vaccines was its versatility, which was a big help when sinister new variants took over.

The platform can be adapted to include genetic information that codes for a variety of different pathogens, especially viruses.

They can also be easily coded to target specific antigens, or proteins that sit on cancer cells and act as signals to the body that something is wrong.

This makes mRNA technology especially attractive for protection against cancers, which are highly specific to each individual patient and require precise treatment tailored specifically to them.

There are currently 35 mRNA cancer vaccine candidates in the pipeline aimed at combating various cancers, including melanoma, bladder, esophageal, kidney, triple negative breast and colorectal cancer.

The umbrella term “cancer” represents hundreds of different diseases, many of which would have been death sentences just a few decades ago.

Thanks to medical milestones in the development of targeted therapies and drugs that prime the immune system to fight cancer cells, some of the most stubborn cancers, such as metastatic melanoma, are highly treatable.

These staggering medical advances mean that cancer patients are a third less likely to die from the disease than they were just thirty years ago. Since 1990, 3.8 million cancer deaths have been averted.