Footprints left in Africa 1.5 million years ago reveal secrets about human evolution

Two species of ancient humans thought not to know each other roamed the plains of Africa side by side 1.5 million years ago, a study suggests.

Archaeologists have discovered four sets of footprints preserved in the mud of Kenya’s Turkana Basin, a site that has been crucial to understanding human evolution.

The discovery is the first direct evidence that very clearly different types of human relatives lived in the same place at the same time, the researchers said.

And the songs also open up the possibility that the two groups collaborated and influenced each other

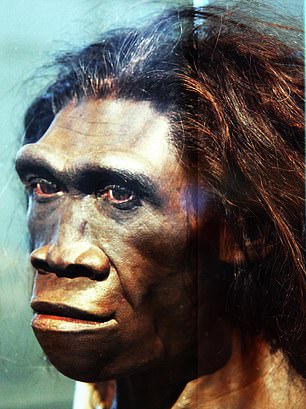

The footprints of Paranthropus boisei, a bipedal primate with smaller brains and broad, flat faces with massive teeth, and Homo erectus, which look more like modern humans and are thought to be our direct ancestors

Researchers noted that the foot structure of P. boisei may not have been ideal for traveling long distances, which could explain why arching in H. erectus survived in later generations.

“One hypothesis states that H. erectus was the first hominin to practice fully modern, human-like bipedal walking and endurance running, and that this adaptation set them on a different evolutionary trajectory,” the team shared in the study.

Whether the two individuals passed the eastern end of Lake Turkana at the same time — or a day or two apart — they likely knew of each other’s existence, said co-author Kevin Hatala, a paleoanthropologist at Chatham University in Pittsburgh.

“They probably saw each other, probably knew each other was there and probably influenced each other in some way,” he said.

Archaeologists have discovered four sets of footprints preserved in the mud of Kenya’s Turkana Basin, a site that has been crucial to understanding human evolution.

One set belonged to a Homo erectus which looks more like modern humans and is believed to be our direct ancestors

The newly discovered footprints provide a snapshot of two human species walking the muddy, submerged edge of a lake millions of years ago.

Researchers were able to distinguish one set of footprints from another using newly developed methods, including 3D analysis techniques that allowed them to capture digital models of the prints for deeper investigation.

“This is the first evidence of two distinct patterns of bipedalism among Pleistocene hominins appearing on the same footprint surface,” the team shared in a statement.

Homo erectus appeared to walk in a manner similar to that of modern humans: it struck the ground with its heel first, rolled its weight over the ball of the foot and toes, and pushed off again.

The other species, P. boisei, also walked upright, but in a “different way than anything we’ve seen before and anywhere else,” says co-author Erin Marie Williams-Hatala, a human evolutionary anatomist at the University of Chatham.

The researchers found that prints made by P. boisei showed similarities to other ancient human tracks, including those found in Laetoli, Tanzania, which are 3.6 million years old.

These tracks belonged to Australopithecus afarensis, a species with pelvic and leg bones nearly identical in function to those of modern humans.

This footprint belonged to Paranthropus boisei, a bipedal primate with smaller brains and broad, flat faces with enormous teeth

Whether the two individuals traveled along the eastern side of Lake Turkana at the same time (or a day or two apart), they likely knew of each other’s existence.

The new discovery suggested that P. boisei had different heel strikes or push-off patterns than those found in Tanzania and modern humans.

P. boisei has been nicknamed ‘Nutcracker Man’ because of its powerful jaws and enormous teeth, which were attached to the large crest on the skull.

The unique walking properties implied that this transformation to bipedalism – walking on two feet – did not occur in a single moment and in one way.

Researchers noted that the foot structure of P. boisei (left) may not have been ideal for traveling long distances, which could explain why arching in H. erectus survived in later generations.

Rather, there may have been several ways that early humans learned to walk, run, stumble, and slide on prehistoric muddy slopes.

The researchers determined that P. boisei would have been size 8.5 in men or size 10 in women. Living Science reported

While H. erectus was approximately a women’s size four to a men’s size six.

Hatala explained that the new data from reveal fascinating details about the evolution of human anatomy and locomotion, and provide further clues about ancient human behavior and environment.

“With this kind of data, we can see how living individuals moved through their environment millions of years ago and possibly interacted with each other, or even with other animals,” he added.

“That’s something we can’t really get from bones or stone tools.”