New venomous species with eight legs and ‘scalloped pincers’ is discovered in California

Scientists have discovered a new poisonous species of scorpion in the California desert.

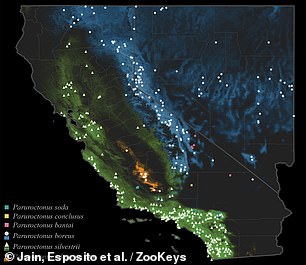

This new species, now called the “Tulare Basin scorpion,” has been found across hundreds of miles of massive desert northwest of Los Angeles.

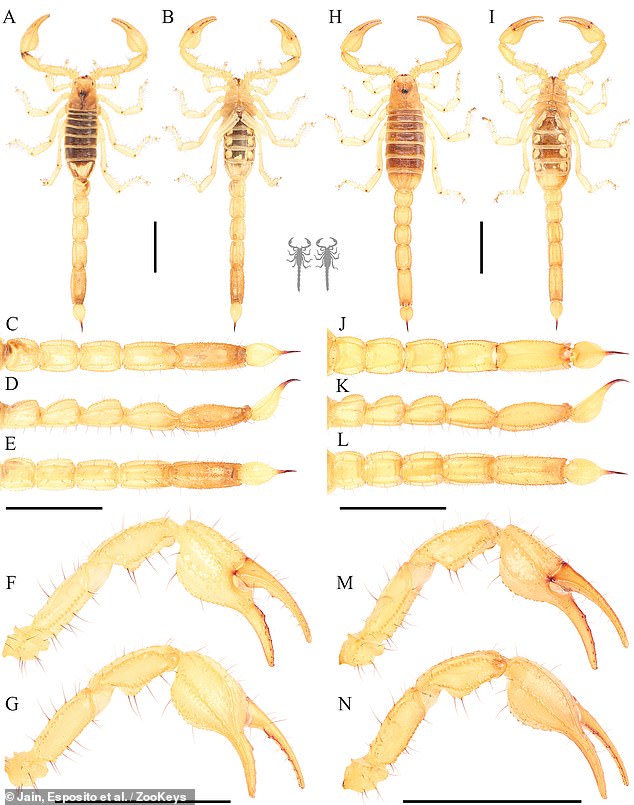

Photographed for the first time amid industrial roadside trash, the 2.1-inch scorpion has survived harsh and toxic conditions amid oil extraction and chemically intensive agriculture throughout central California's San Joaquin Desert.

However, the creature's passion for these barren desert lands is no indication of its lethality: one arachnologist who studied the new scorpion told DailyMail.com that its sting was like a “cactus prick.”

But “they were in a very unusual location,” according to the California Academy of Sciences-trained researcher, who made first contact with the citizen scientist who discovered this unusual scorpion.

Scientists have obtained 29 specimens of an entirely new species of venomous scorpion, one with unique thick claws, after a dedicated civilian researcher discovered one for the first time in California's San Joaquin Desert. “They were in a very unusual place,” one researcher said.

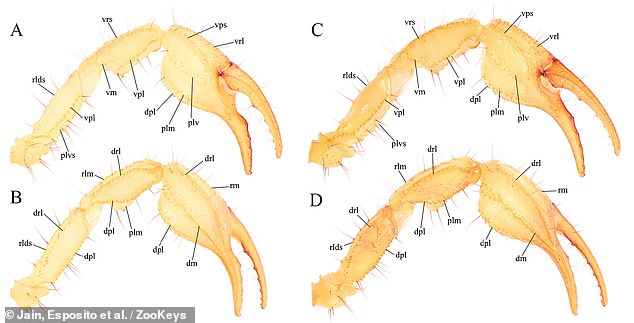

Their unique “scorpion pincers” shape varies between males and females of this species, and their orange-yellow bodies appear to tan in the desert sun.

“I was very excited to collect it because it was one of the first new species I found,” Prakrit Jain, an evolutionary biology student trained at UC Berkeley, told a local news site. sfget.

Jain got the advice from a fellow user of the social media app iNaturalist, an amateur reptile hunter named Brian Hind, who was puzzled by the creatures' unusual claws.

Jane, along with another young citizen scientist, Harper Forbes, and assistant curator of the California Academy of Sciences, Arachnologist Lauren Espositowork has begun to track down more examples of the Tulare Basin scorpion.

Armed with black lights, the team searched the rugged desert terrain from Kern County to Fresno for specimens of the new species.

Armed with black lights, the team searched the rugged desert terrain from Kern County to Fresno in search of more specimens of the new species.

Scorpio, its official name now Paroroctonus tularihas been shown to be one of many related scorpions that have adapted to very specific, sub-humid or mesic areas of the California desert.

The scorpion's unique “scalloped pincer” shape varies between males and females of the species, and their orange-yellow bodies appear to tan in the desert sun.

“Individuals from the southeastern and southwestern regions are generally darker and more orange,” Jain, Esposito and co-authors wrote in their new journal article on the creature, published in late November. ZooKeys.

The color was “somewhat variable, ranging from bright yellow to orange and dark brown,” they wrote.

Despite these obvious differences, the eight-legged, striped, and smooth-bodied scorpions only differ in “fewer than four single nucleotide polymorphisms.”

Although venomous, the Tulare Basin scorpion is not dangerous enough to pose a threat to humans, Esposito told DailyMail.com.

“The poison has very little effect on humans,” Esposito wrote via email.

“At worst, it would be similar to a mild bee sting, but unlikely to be much different from a cactus sting.”

The scorpion, which was photographed for the first time amidst industrial garbage, has survived harsh conditions amid oil extraction and chemically intensive agriculture in central California.

The team argues that these species should “receive endangered or critically endangered species status, at least at the state level,” a process that involves helping native plants as well.

The scorpion's color was “somewhat variable, ranging from bright yellow to orange and dark brown,” the researchers wrote. Despite these obvious differences, striped scorpions only differ in fewer than four single nucleotide polymorphisms, genetically.

The scorpion actually faces “a number of imminent threats to its survival,” most of which are man-made or man-made, the researchers said.

Livestock grazing appears to be one of the human activities currently threatening the scorpion, researchers suspect, because it has spread non-native plants that are choking out the native grass species that the younger Tulare Basin scorpions depend on.

“Juveniles appear to depend on it, and there is the potential for soil compaction that could affect the construction or maintenance of burrows in soft clay soil,” the researchers wrote.

The team argues that these species should “receive endangered or critically endangered species status, at least at the state level,” a process that would include helping native plants as well.

“The most important step toward Tulare Basin scorpion conservation is to maintain alkaline pond plant communities by protecting remaining high-quality habitat, controlling invasive species, reducing livestock grazing, restoring abandoned lands, and combating causes and causes.” Impacts of climate change, the researchers wrote.

Esposito said she was “optimistic” and that the discovery of the new scorpion was “a great example of collecting enough data on one thing that can preserve habitat for many, many other things.”

(Tags for translation)dailymail