You should NEVER skip breakfast if you are trying to lose weight. Scientists reveal what it can do to the body

Those looking to shed the extra pounds packed in over the festive period should not skip breakfast, Spanish scientists have suggested.

Instead, dieters should aim to eat between 20 and 30 percent of their daily energy intake before the most important meal of the day.

That’s between 500-750 calories for men and 400-600 for women.

In a study that tracked the diet and health of nearly 400 adults for three years, scientists found that those who consumed this sweet spot amount of energy for breakfast had a lower body mass index (BMI) than those who consumed too much energy. ate little. or too much for breakfast.

While a full English breakfast provides too many calories at almost 900 calories, a healthy bowl of porridge may provide too few at just 200 calories.

But a McDonald’s sausage and egg McMuffin would be just right for women at 423 calories.

In the study, published in The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Agingscientists compared the nutritional and health data of 383 adults aged 55 to 75 in a hospital in Barcelona.

People who want to lose weight should not skip breakfast, according to a new Spanish study

All participants were obese and diagnosed with metabolic syndrome – a cluster of conditions such as high blood pressure and high cholesterol that increase the risk of heart problems and diabetes.

They also took part in a clinical trial where experts put them on a Mediterranean diet, rich in vegetables and whole grains, in an effort to help them lose weight.

Scientists monitored participants’ calorie intake at breakfast at the start of the study, two years later, and then one final time at the end of the three-year study.

Participants’ health data was collected at several points during the study.

The scientists found that those who ate too much or too little for breakfast had a 2 to 3.5 percent higher BMI than those who ate the perfect amount.

The same applied to waist circumference, a measure of how much fat collects around vital organs in the abdomen.

Those who ate too little or too much for breakfast had a waist size that was 2 to 4 percent larger than those in the sweet spot zone.

Analysis of blood tests also showed that people who ate too little for breakfast had higher levels of fat in their blood – which is considered a risk factor for heart disease.

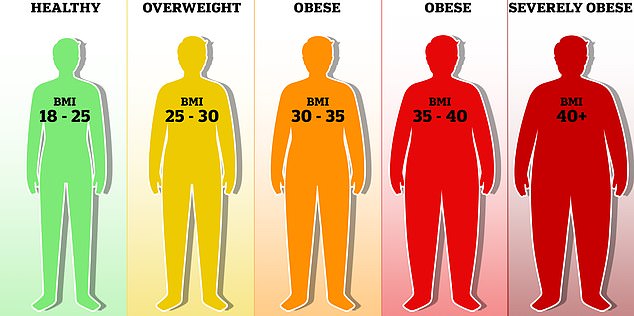

According to the BMI system, a score of 18.5 to 25 is healthy. A score of 25 to 29 counts as overweight, and 30-plus means someone is obese, the stage at which the risk of disease increases dramatically

But it wasn’t just about calories, scientists also analyzed the nutritional quality of the breakfast the participants ate.

They found that those who ate an unhealthier breakfast – such as foods high in fat, salt and sugar, such as fried meat – also had a greater risk of poor health outcomes, regardless of calorie content.

While higher BMI and waist circumference make sense for those who eat too much breakfast, the reason why those who ate less also had similar results seems contradictory at first glance.

The scientists suggested this had something to do with the fact that those who eat breakfast feel fuller during the day and eat fewer calories overall due to fewer snacks.

Professor Álvaro Hernáez, author of the study and an expert in health sciences at Ramon Llull University, said: ‘Breakfast is the most important meal of the day, but what and how you eat it matters.’

‘Eating controlled amounts – not too much or too little – and ensuring good nutritional composition is crucial.

‘Our data show that quality is associated with better cardiovascular risk factor outcomes. It’s just as important to eat breakfast as it is to have a good breakfast.’

The study has some limitations that the authors acknowledge.

First, it is observational, meaning that although data suggested a link between calorie intake at breakfast and health outcomes, researchers could not prove this was the case.

While the scientists tried to compensate for other factors, such as the level of exercise the participants reported, there could be another factor they didn’t take into account that affected the results.

Furthermore, breakfast data was collected through surveying participants, meaning the information was dependent on participants’ memory and honesty.