Yellowstone crater’s movement sparks fears of supervolcano explosion as scientists assess risk

Scientists investigating the Yellowstone supervolcano have discovered movement deep within the crater, sparking fears the sleeping giant could erupt.

The volcano, located beneath Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, can produce a devastating eruption of magnitude 8.

And because the volcano hasn’t exploded in about 640,000 years, some experts and locals believe the volcano is long overdue.

Researchers analyzing the supervolcano’s crater, or caldera, found that magma inside is moving northeastward, shifting the concentration of volcanic activity.

That means that if the volcano were to erupt, it would happen in this area, compared to previous warnings in the western region.

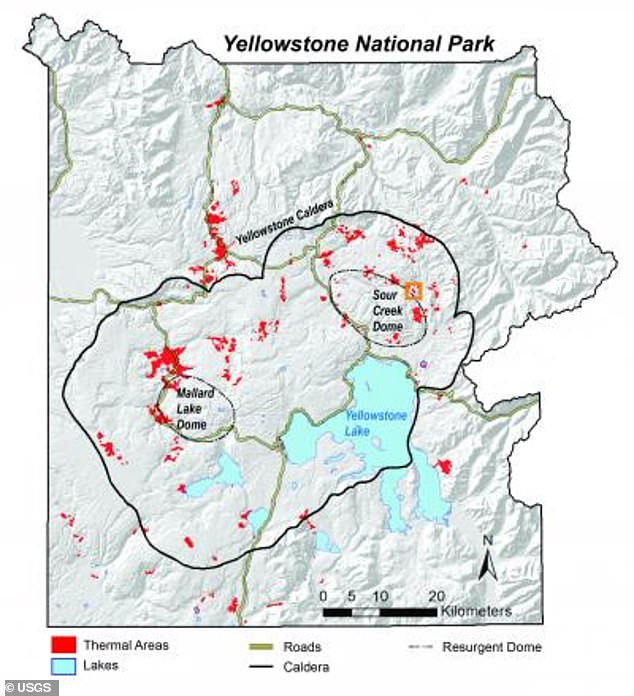

The Yellowstone Caldera is the 1,350 square kilometer crater in the west-central part of the park that was formed when this volcano catastrophically erupted hundreds of thousands of years ago.

The team found that most of this magma is stored in separate underground reservoirs, preventing it from becoming concentrated enough to cause an eruption.

While an eruption could occur in the northeastern region as a result of the shift, researchers said their findings suggest the supervolcano will not erupt within our lifetime.

A new study has found that the movement of magma beneath the Yellowstone supervolcano is shifting in a new direction. Pictured is the Grand Prismatic Spring which sits atop the underground supervolcano

The Old Faithful Geyser erupts in Yellowstone National Park. This natural wonder is powered by the volcanism of the Yellowstone Caldera

“Nowhere in Yellowstone do we have regions that could erupt,” lead author Ninfa Bennington, a research geophysicist at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, told the WashingtonPost.

‘There is a lot of magma in it, but the magma is not connected enough.’

Bennington and her colleagues conducted a large-scale magnetotelluric survey in the Yellowstone Caldera.

The technique works by listening to the Earth’s natural ‘signals’, such as radio waves and magnetic vibrations that come from space or deep within our planet.

These signals change depending on what kinds of things – such as rocks, water or metals – are underground.

This allowed the researchers to look inside the crater and investigate what was really happening beneath the surface.

They used the resulting data to map the magma formations beneath the Caldera.

The results indicated that there are at least seven main areas of high magma content at depths between 4.5 and 50 kilometers below the surface, showing that these reservoirs are ‘not erupting’.

The researchers published their findings in the journal Nature on Wednesday.

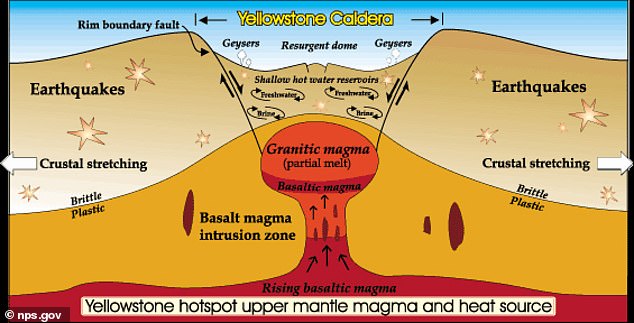

Previous research has shown that there are two types of magma beneath the Yellowstone Caldera.

One of these is basaltic magma, which is usually produced by direct melting of the Earth’s mantle, according to the US Geological Survey (USGS).

The Yellowstone Caldera is the 1,350 square kilometer crater in the west-central part of the park that formed when this volcano erupted cataclysmically about 640,000 years ago.

Deep beneath the Caldera, the magma fueling the supervolcano’s activity now appears to be moving northeast of this massive crater, shifting the concentration of volcanic activity

Basaltic magma erupts more easily due to lower flow resistance. But this magma is compact and deeply buried beneath the Yellowstone Caldera, meaning it is unlikely to cause an eruption there.

The other type is rhyolitic magma, which is thicker and more resistant to flow due to its high silica content.

Below Yellowstone, deep-seated basaltic magma heats the surrounding rock, creating rhyolitic magma closer to the surface.

But it would take a major build-up of pressure for rhyolitic magma to erupt from Yellowstone.

However, it has happened before. Over the past two million years, Yellowstone has produced three major, caldera-forming eruptions, all powered by reservoirs of rhyolitic magma.

But this is unlikely to happen again, at least within our lifetimes, the researchers said.

Based on the volume of rhyolitic magma storage beneath the northeastern Yellowstone Caldera, and the region’s direct connection to a heat source in the lower crust, the researchers concluded that the concentration of future rhyolitic volcanic activity has shifted northeastward.

This is an important change. Rhyolitic volcanic activity has occurred over the past 160,000 years across most of the Yellowstone Caldera, excluding this northeastern region, the researchers wrote in their report.

Due to the large amount of magma beneath the National Park, this region will remain volcanically active, according to Bennington.

But her research suggests tourists won’t have to worry about the threat of a major eruption anytime soon.