Wyoming ranchers fear wolves released into wild by Colorado government to boost endangered species are on verge of crossing state line – with law letting them SHOOT the predators on sight

Ranchers in Wyoming are sounding the alarm after wolves reintroduced to Colorado were spotted near the… state border.

“Wolves can travel 50 miles in a day, so that doesn’t surprise me at all,” Howard Cooper told Cowboy State Daily. Wolves have been spotted in Walden – just 20 miles from Wyoming – meaning the predators could theoretically enter the Cowboy State today.

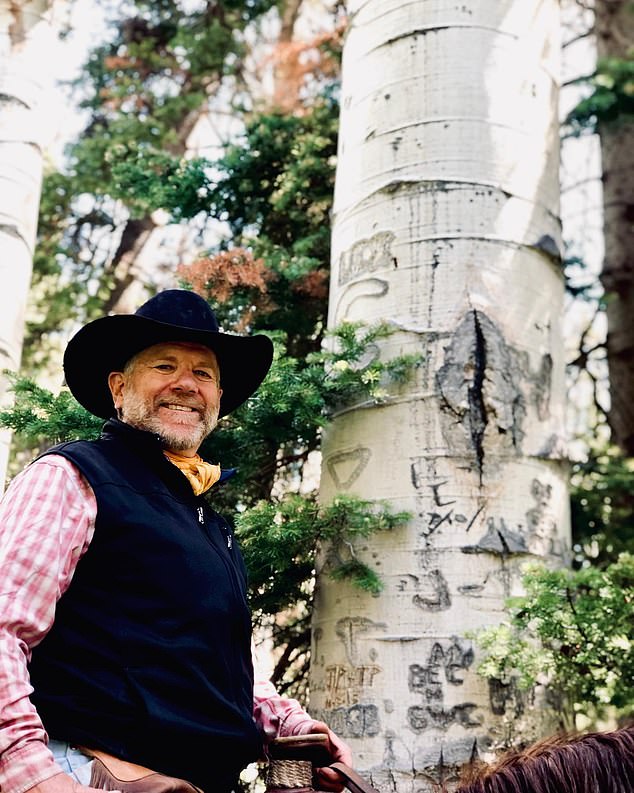

The farmer from Meeker, Colorado, opposes the reintroduction of gray wolves in the neighboring state and supports a lobby group that aims to prevent further wolf releases.

Wolves in Colorado are federally protected and are not allowed to be hunted or killed by the general public.

But by crossing the border, a wolf enters Wyoming’s 53 million-acre “predator zone” — which covers roughly 85 percent of the state — and goes from a state-endangered animal to one that can be shot on the spot.

A gray wolf sighting occurred in Walden, Colorado, about 20 miles (32 kilometers) from the state line, raising concerns among ranchers

Howard Cooper, a rancher in Meeker, Colorado, supports a group that plans to stop the future release of gray wolves in the state

Ten gray wolves have been released so far, and fifteen more will be released between December 2024 and March 2025.

Some Wyoming ranchers have said they are willing to use whatever means necessary to defend their livestock.

“The positive thing is that if any of those wolves cross the border into Wyoming, they are no longer protected. They are classified as predators and can be removed,” said sheep farmer Jim Magagna.

There have already been problems. In September, the Colorado Sun reported that at least one wolf was killed after crossing into Wyoming.

The publication cited reports from ranchers and other stakeholders, but Wyoming officials declined to confirm the death.

Instead, they claimed the information was confidential under an 11-year-old state policy intended to mask the identities of people who legally kill wolves in the state.

Reintroduction has proven to be a controversial issue. Gray wolves were nearly exterminated in the 20th century.

In 1905, the federal government infected the animals with mange. Ten years later, Congress passed a law requiring their removal from federal territory.

By 1960, the animals were all but wiped out from their former range – on the same pretext that they posed a threat to livestock and big game.

Despite ranchers’ concerns, Colorado Parks and Wildlife spokesman Joey Livingston said he had full confidence in the agency’s “buffer zone” policy.

Jim Magagna, a Wyoming sheep farmer, called it a “positive thing” that wolves “can be removed” if they cross state lines

The species was nearly driven to extinction in the 20th century as there were concerns that it posed a threat to big game and livestock

“Scientists found that wolves released in Yellowstone and central Idaho in the mid-1990s traveled significant distances in the months immediately following their release,” he explained.

“The average distance was about 50 miles, ranging from about 14 to 85 miles from the discharge locations.

“As a result, the releases in Colorado occurred a minimum of 60 miles from the northern border with Wyoming, the western border with Utah, the southern border of New Mexico, as well as a similar buffer, as requested by the tribes, from sovereign tribes. lands in southwestern Colorado.”

The state’s reintroduction program was mandated by a voter-backed initiative called Proposition 114. The bill passed in November 2020 by a margin of 50.91 percent to 49.09 percent.

Proposition 114 required the Parks and Wildlife Commission to “develop a plan to recover and manage gray wolves in Colorado using the best scientific data available” and “conduct statewide hearings to gather information that will can be taken into account in developing such a plan,” CPW said.

Oregon agreed to provide the first 10 wolves, which were released onto public lands in Grand and Summit counties.

CPW praised it as “a historic effort to create a permanent, self-sustaining wolf population and fulfill a voter-approved initiative to restore gray wolves in Colorado.”

Colorado Parks and Wildlife aims to ‘restore and manage’ a population in the state ‘using the best scientific data available’

Magagna and other ranchers — including those in Colorado, where the wolves were released — are concerned about the potential threat to farm animals

Opponents of the reintroduction plan have argued that some wolves came from Oregon packs with a history of livestock depredation.

But opponents argued that some wolves came from Oregon packs with a history of attacking livestock.

Fifteen more wolves will be released between December 2024 and March 2025 through an agreement with the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation.

However, the Colorado Conservation Alliance — a coalition of ranchers, hunters and entrepreneurs — is pushing to halt further releases.

Cooper is one of the financiers of the CCA. He is the owner of Three Crowns Ranch, billed as a “hunting destination” with opportunities to shoot private country elk, mule deer, elk, black bears and mountain lions.

The group filed a lawsuit in December, focusing on concerns about how the gray wolves might interact with Mexican wolves in Arizona and New Mexico. The lawsuit touches on several other hypotheses, including the possible spread of disease.

“There are important environmental concerns that have not been addressed by Defendants regarding the introduction of wolves into Colorado,” the complaint reads in part.

Earlier that week, another lawsuit was filed by the Gunnison County Stockgrowers and Colorado Cattlemen associations, demanding an immediate halt to the reintroduction.

Cooper, the owner of Three Crowns Ranch (pictured) is a funder of the Colorado Conservation Alliance, a coalition of hunters, ranchers and entrepreneurs

He and members of the group allege that Colorado officials have not adequately addressed “significant environmental concerns.”

According to CPW, it is not a matter of whether or not you want wolves.

“We have long anticipated that gray wolves would eventually enter the state, as some have already done, and we are prepared for their arrival,” the agency wrote on its website.

And some experts argue that wolves are needed to balance the ecosystem.

Speaking to Rocky Mountain PBS after the release of the first five wolves, Joanna Lambert, professor of wildlife ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado, sounded triumphant.

“This is a moment of going wild again,” she said. ‘From doing something to prevent the biodiversity extinction crisis we live in… to making a difference in this age of extinction.

“And what’s more, this is a source of hope not only for all of us standing here, but also for our younger generations.”