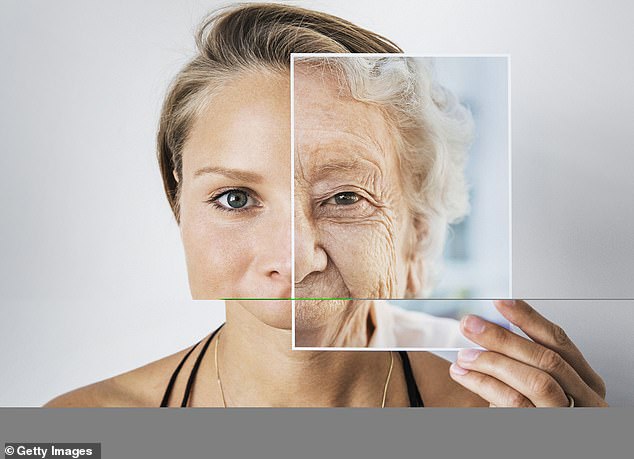

Why you inherited your emotional trauma from your parents, passed on through their genes

Can you inherit the emotional scars caused by trauma and stress experienced by your parents, or even your grandparents?

Not just because of the psychological damage caused to those who suffer from it – but also because of changes in their genes that are then passed on to their children?

A growing body of evidence suggests this may be the case.

‘Intergenerational harm’ is the term often used to describe the harrowing psychological legacies such as those of the Holocaust and apartheid in South Africa.

But now scientists are discovering a new possibility – that we can also physically pass on trauma through our altered genes (where certain genes are turned ‘on’ or ‘off’).

A growing body of evidence suggests that you can inherit the emotional scars caused by the trauma and stress experienced by your parents, or even your grandparents.

One of the last studies to suggest this was based on analysis of the genes of more than 900 British boys and girls whose mothers had been physically abused by their fathers as children.

The study, published in the journal Epigenetics, used data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, an ongoing project that started in the 1990s. The new analysis, conducted by Syracuse University in New York, identified 903 mothers who said they had been physically abused by their fathers.

Previous research had identified genetic changes in women who had been abused. When the scientists examined DNA from the umbilical cord blood of the children in the Avon study, they found similar changes to those in abused women, suggesting that altered genes have been passed on.

These changes in genes are known as epigenetic changes – caused as a result of our environment or lifestyle, such as smoking. Such changes can then alter our physical health or emotional behavior.

When the researchers examined the children’s psychiatric reports at school at age seven, their levels of anxiety, fear and depression correlated closely with their inherited gene changes.

The idea that we could somehow inherit behavior from previous generations was originally proposed more than 200 years ago by the pioneering French biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, but at the time his ideas were ridiculed.

In recent years, however, laboratory experiments have begun to prove the value of this theory, not only in terms of the environment in which children grow up, but also in terms of actual changes in their DNA.

A groundbreaking 2010 study found that when mouse pups were suddenly taken from their mothers, they grew up with depressive behavior and became unusually anxious when introduced to a new environment.

DNA testing showed that the mice showed epigenetic changes in genes linked to trauma and anxiety, lead researcher Isabelle Mansuy, professor of neuroepigenetics at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, wrote in the journal Biological Psychiatry.

What’s more, when the male pups themselves fathered offspring, they showed exaggerated fear and trauma responses and gene changes, despite being raised in a normal environment, Professor Mansuy reported.

More recently, Rachel Yehuda, professor of psychiatry and neuroscience of trauma at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, discovered an epigenetic change in Nazi concentration camp survivors and their descendants.

As her research shows, many Holocaust survivors suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other emotional conditions. But she has now shown that it is not ‘just’ the home environment that causes this, but the hereditary genes.

A 2016 study published in the journal Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy found that one in five children of Holocaust survivors had generalized anxiety, characterized by uncontrollable, irrational worries.

But in a recent study involving 32 survivors and 22 of their adult children, Professor Yehuda discovered epigenetic changes in the same region of the FKBP5 gene (linked to anxiety and other mental health problems) in the survivors and their children. The changes were not found in a comparison group of Jewish parents and their children who had lived outside Nazi-occupied Europe.

Scientists discover a new possibility: that we can also physically pass on trauma through our altered genes

As an evolutionary adaptation, increased vigilance and fear can help offspring survive threatening environments, says Professor Yehuda: ‘If you live in adversity, you may have the skills to survive it, honed from past life lessons. But if you don’t have adversity, you can become emotionally hyper-vigilant.’

Fathers can pass on stress-induced genetic changes to their sperm, according to a 2019 study from Queensland University of Technology in Australia.

When the researchers compared genes in the sperm of veterans with and without PTSD, they found epigenetic changes linked to stress and anxiety in the veterans’ now-adult children if their fathers had PTSD — but not in the others.

Professor Yehuda says this means a life-changing experience, “that doesn’t just die with you. It then takes on a life of its own in one form or another. The implications are that what happens to our parents, or perhaps even our grandparents, can help shape who we are at a fundamental, molecular level that contributes to our behavior, our beliefs, our strengths and our vulnerabilities.’

Measurable physical effects can even occur in the brains of traumatized children, according to research from Sakarya University in Turkey in 2022.

They scanned the brains of forty children whose mothers were exposed as teenagers to an earthquake that struck Turkey in 1999.

Compared to scans of 27 children born to mothers who had not experienced the earthquakes, the trauma group had significantly smaller amygdala and hippocampus in their brains.

These areas “play an important role in relation to post-traumatic physiological responses,” the journal Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging reported. ‘Our research shows that there may be a relationship between intergenerational trauma and different brain structures.’

Dr. Chloe Wong, senior lecturer in epigenetics at King’s College London, believes that hereditary stress can have a major impact on our lives.

“Children of traumatized mothers inherit that stress in the womb,” she says. ‘Studies have even shown that their DNA changes are different depending on their age in the womb when the stress occurred.’ She adds that research has also shown that “hereditary stress” can even accelerate the rate at which your body and brain age.

However, not everyone is convinced of the power of this relationship. Dr. Heather Sequeira, a consultant psychologist with a special interest in trauma based in London, told Good Health that the behavior of traumatized parents can have a much more powerful impact on their children’s mental health than any genetic inheritance.

“It is impossible to separate the emotional influence of parents from epigenetic transmission,” she says. ‘They are entangled. It is multi-faceted and intertwined.”

Traumatized mothers’ inability to bond with their babies early on could have a particularly strong influence.

Dr. Heather Sequeira says: ‘Being raised by someone who does not feel safe and relaxed can have serious consequences for communicating traumatic feelings. In the first three to five weeks of life, the baby’s nervous system is in a crucial phase. Failure to form strong parental bonds can impact subsequent psychological development.”

But whether these stresses can be passed on to grandchildren has not yet been fully confirmed, says Dr Chloe Wong. ‘Research suggests that most of our epigenetic inheritance appears to have been wiped out before the grandchildren’s generation.’

The good news, she says, is that studies show that “harmful epigenetic changes are reversible.”

Professor Mansuy’s research has shown that when mouse pups who had been traumatized early in life were placed in cages that had a very rich supportive environment – with running wheels, toys, a maze and plenty of other mice to socialize with – their gene changes decreased and they showed no trauma symptoms. Neither do their descendants.

Dr. Chloe Wong explains: ‘We know that people who exercise, eat healthy and get enough sleep have a younger epigenetic age. Everything you do can change your epigen for the better or worse.”

Dr. Heather Sequeira says the biggest threat is that epigenetic changes can lead to chronic inflammation, “one of the biggest dangers to the brain and body.”

‘Numerous studies show that such chronic inflammation can be suppressed by healthy eating such as a Mediterranean diet, regular exercise, meditation, mindfulness – and not eating ultra-processed foods (because they are anti-inflammatory). All the more reason to take care of ourselves.’

And who knows, your grandchildren (and even their children) may end up thanking you for it.