Why was Iran’s Islamist ex-deputy defence minister given UK citizenship in the late 2000s?

>

One day in the late 2000s, a 40-something man named Alireza Akbari left his native Iran and travelled to London hoping to start a new life with his wife Maryam and their daughters Atefah and Faezah.

It was the height of the so-called War on Terror. Which was awkward, since Mr Akbari happened to be a former Deputy Minister in the Islamist theocracy’s notoriously corrupt and despotic government.

Yet, somehow, this man’s arrival in the UK was happily sanctioned by the British authorities: they first granted him a so-called ‘investor visa’ and then, a few years later, handed out a UK passport.

The Akbari family could therefore settle in Hammersmith, West London.

One day in the late 2000s, a 40-something man named Alireza Akbari left his native Iran and travelled to London hoping to start a new life

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei pictured on January 12, two days before Mr Akbari was killed

Daughter Atefah, who was already an adult, enrolled at a university in the capital. Faezah went to a local primary school. Mum stayed at home. Dad pursued a career in business.

So began a journey that ended last week in a sudden, violent and utterly tragic fashion.

On Saturday, the Iranian regime announced that it had executed Akbari by hanging. He was 61. It seems that he’d been secretly held in custody there since 2019.

The crime for which he paid with his life? Espionage. According to Iran, Akbari — who helped found its repressive regime — had actually spent recent years working as a ‘spy’ for the UK.

It’s a sensational claim. Which is one reason why the death of Akbari, a dual national who becomes the first person with a British passport to suffer the death penalty since the 1980s, has sparked a major diplomatic incident which remains in serious danger of boiling over.

Rishi Sunak, who immediately withdrew the UK’s ambassador to Tehran, has called the execution ‘ruthless and cowardly’. Foreign Secretary James Cleverly summoned the regime’s Charge d’affaires to express ‘disgust’. Sanctions were this week imposed and condemnatory statements issued by the UK, the U.S., and the EU.

And the UK is also considering declaring Iran’s Revolutionary Guard — the most fearsome branch of the regime’s Armed Forces of which Akbari was himself once a member — a terrorist organisation.

Even Prince Harry has been dragged into the row. On Tuesday, Iran’s foreign ministry issued a statement flagging his autobiography’s disclosure that he’d killed 25 Taliban fighters — or, as Iran sees them, ‘innocent people’ — in Afghanistan.

This, the Iranian statement alleged, leaves the UK ‘in no position to preach [to] others on human rights’.

Akbari’s grieving family have, for their part, vigorously protested his innocence, saying his conviction on a medieval-sounding charge called ‘corruption on earth’ was based on a false confession obtained via torture.

Relatives say that, prior to Akbari’s death, he’d been held in captivity for three years, often in solitary confinement. During this period, they say interrogators consistently subjected him to degrading and inhumane treatment.

Akbari himself offered some insight into his incarceration via a taped statement, smuggled out of prison just before his death.

‘They broke my will, drove me to madness and forced me to do whatever they wanted,’ he said. ‘By the force of gun and death threats they made me confess to false and corrupt claims.’

To understand how this awful tale unfolded, we must first explore the two competing narratives about how he arrived in the UK in the first place.

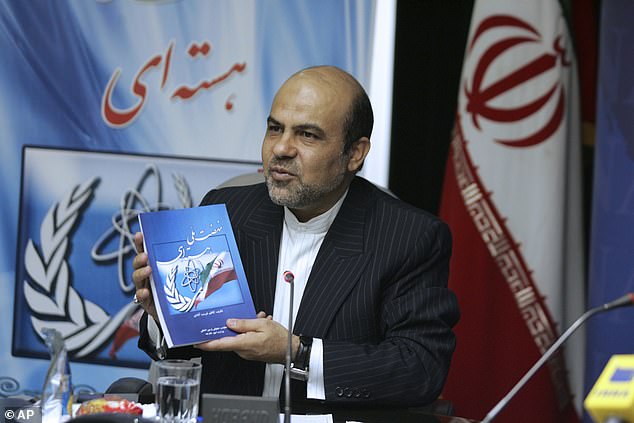

Relatives say that, prior to Akbari’s (pictured in 2008) death, he’d been held in captivity for three years, often in solitary confinement

Akbari was reportedly one of the first-ever members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard (Pictured: Members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) attend an IRGC ground forces military drill in the Aras area, October 2022)

One has been aired in court by the Iranian authorities. They reckon the whole thing was a sort of defection, masterminded by MI6 agents who then paid him millions of pounds in return for providing information about the regime and, in particular, its nuclear ambitions.

They claim that, in a stunt that reads like something out of a James Bond novel, Akbari was instructed to fake a stroke during a 2008 business trip to Vienna. This allegedly gave his wife and daughters a cover story to fly out from Iran to be at his bedside. The whole family could then be spirited away to Britain, by the security services.

The Akbari family, for their part, argue — with some justification — that there are significant flaws in this narrative.

For starters, there is no documented evidence of him being paid cash by British authorities.

What’s more, they insist that he actually chose to remove himself from Iran to escape political persecution of a sort common under the despotic theocracy, where competing factions constantly juggle for supremacy, and those in power habitually jail and persecute opponents.

The family has argued that Akbari was caught up in a power struggle between supporters of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the hard-line anti-Western President of Iran from 2005-2013, and his predecessor Mohammad Khatami, a comparative reformer under whom Akbari had previously served as Deputy Defence Minister.

‘I recall there being a period around 2008 where he ended up in prison,’ Akbari’s nephew Ramin Forghani, who now lives in Luxembourg, told me this week.

‘He was released on bail, but there was talk of him having suffered trauma there, and it didn’t feel safe staying behind, so he got permission to go to Europe on a business trip and was then able to apply for a UK visa.’

A so-called ‘investor visa’ does indeed appear to have been granted to Akbari around this time. It was issued under a scheme popularised by the Blair government, through which wealthy foreigners with a spare £2million to park in the UK were allowed to legally move here and, after three years, become a naturalised citizen.

The system was abolished in February last year by the then Home Secretary Priti Patel, amid widespread concern that it had been routinely abused by generations of dubious oligarchs and other immigrants from questionable corners of the globe who had grown rich via the proceeds of corruption.

While we must, of course, assume that the cash Akbari used to acquire this visa was legitimately obtained, it’s unclear how he reconciled his decision to move to the UK — or indeed anywhere in the enlightened West — with his apparent affection for Iran’s repressive theocracy.

Akbari was, after all, one of the original architects of the barbaric regime.

Born in October 1961, in the city of Shiraz in Iran’s Fars Province, he seems to have cut his political teeth as an activist in the local Association of Student Islamic Societies. The group backed the 1979 revolution that saw the last Shah of Iran ousted by religious fundamentalists and that ushered the Ayatollahs into power.

Devoted to the Islamist cause, he spent most of the 1980s as a soldier in the Revolutionary Guard which was by then fighting the Iran-Iraq war.

In 1989, Akbari swore fealty to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei when he became Supreme Leader, and by the 1990s was climbing the greasy pole of government, eventually becoming the deputy defence minister under President Mohammad Khatami responsible for negotiating security agreements with Iran’s strategic allies.

Ironically, given his subsequent path, he appears to have been a staunch opponent of the West and supporter of Iran’s controversial nuclear programme. In 2000, he even travelled to Moscow for a ’round table’ meeting with Russian allies and, in a media interview, spoke out in support of Putin’s war in Chechnya, saying: ‘These actions match the interests of stability in the entire region of the greater Caucasus.’

Having left office in 2005, Akbari remained outwardly loyal to Iran’s ruling theocracy, even after his move to the UK — a fact that caused deep divisions in his own family.

His nephew Ramin Forghani, a human rights campaigner who fled Iran and moved to Scotland in 2013 (before settling in Luxembourg), told me: ‘After I became a political activist in Scotland, and started speaking out against the regime, he cut all contact with me.

‘He seemed to be devoted to the country and the regime, had served it at the highest levels and was one of the first members of the Revolutionary Guard. This is why the spying allegation makes so little sense.’

Quite why the UK agreed to grant citizenship to such an outspoken ally of the Iranian regime is anyone’s guess.

What also makes only limited sense, from such public records as are available, is Akbari’s subsequent business career.

While his wife Maryam and their daughters seem to have mostly remained in London from the late 2000s, he seems to have actually spent large portions of time in Europe.

Profiles on Facebook and Twitter suggest he was based largely in Vienna and Marbella — on the Costa Del Sol in Spain from around 2014 onwards — while a media interview he gave in early 2019 suggested that his principal residence was Gibraltar.

The events that led to Akbari’s arrest and subsequent execution began in 2018, when his former political superior Ali Shamkhani (pictured), who is now secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, invited him to the Iranian city of Karaj

On social media, he claimed to be the founder of a think tank called the Tasmim Strategic Research Institute, and it is possible that he provided strategic advice to companies seeking to do business in Tehran.

He has no listed company directorships in the UK, but may also have dealt in precious stones (his Facebook page contains images of several pieces of valuable-looking jewellery).

On Twitter, he has in recent years adopted a hawkish and largely anti-Western tone in debates about Iran’s nuclear ambitions and has occasionally voiced support for Jeremy Corbyn — who has often been called an apologist for the regime, and appeared multiple times on Press TV, the now-banned propaganda outlet of the ruling theocracy.

The events that led to Akbari’s arrest and subsequent execution began in 2018, when his former political superior Ali Shamkhani, who is now secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, invited him to the Iranian city of Karaj to join a group of experts discussing the regime’s relations with the West.

That visit appears to have been a success, as he agreed to continue helping Iran’s government by returning for similar talks the following year (an unlikely decision, one might argue, if he really was a spy).

Sadly, the second trip saw him get no further than Tehran airport, where he was immediately arrested.

It was this week suggested that Shamkhani — who is embroiled in an ongoing power struggle with hard-line opponents — may have tricked Akbari into returning in order to demonstrate his own loyalty to the regime.

Yet while such things are certainly possible, in the murky and murderous world of Iranian politics, other informed observers believe Akbari was actually arrested as part of a plot to undermine his former political mentor.

‘He was Shamkhani’s man, so it feels like a personal, brutal defenestration of his fiefdom,’ said one insider.

‘Think of it as part of a fight to gain absolute control in which one side has used conspicuous cruelty to humiliate the other. There are mafia factions all trying to teach each other a lesson. The spy stuff is just a smokescreen.’

For three years, Akbari was locked up largely at Tehran’s notorious Evin Prison — where previous inmates include Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, the Iranian-British dual national who was detained on alleged spying charges from 2016 to 2022.

His fate was kept secret after his immediate family chose, on the advice of the UK Foreign Office, not to seek publicity.

That policy only changed last week when it became apparent that his execution was imminent after his daughter Atefah was called to his cell for a final meeting (it is not clear if she was in Iran already or if she had travelled back specifically). By then, of course, it was too late to save him.

Amid the diplomatic fallout, a host of questions surrounds the highly unusual life of Alireza Akbari. But many of the answers have now been taken to his grave.