Why Anthony Albanese’s immigration policies are worsening the housing crisis

Labour’s record high immigration levels are worsening Australia’s housing crisis, with a peak group of homeless people now demanding even more new homes than planned.

In the year to August, 413,530 permanent and long-term migrants arrived in Australia.

If the existing trend continues, the net annual figure could exceed 500,000, which would mark a new record.

This would be much higher than the Treasury’s forecast of 315,000 new arrivals for this budget year, including skilled migrants and international students, made in the May budget.

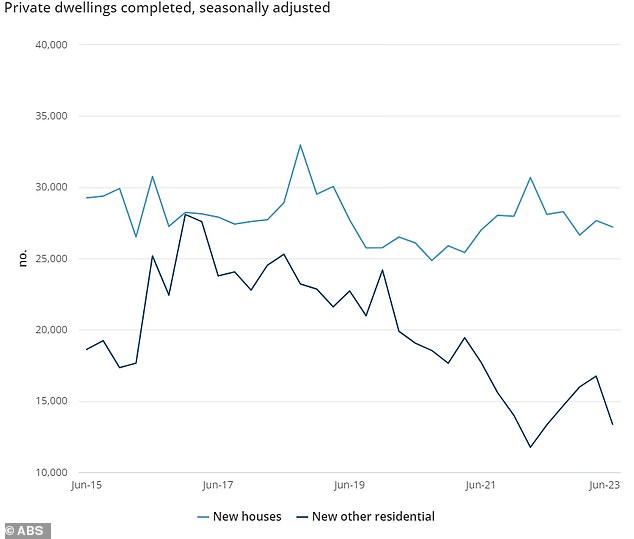

But only 168,231 private residential properties – made up of houses and units – were built during the last financial year, according to Australian Bureau of Statistics figures released this month.

Labour’s record high immigration levels are worsening Australia’s housing crisis – with a peak group of homeless people now demanding even more new homes than planned (pictured is a row of rental properties in Sydney)

Considering Australian homes have an average population of 2.5 according to the 2021 census, that would be enough to house 420,578 people.

That’s far less than Australia’s total population growth of 563,200 for the year to March, including net immigration and births minus deaths.

Homelessness Australia CEO Kate Colvin is calling on the federal and state governments to build 50,000 social and affordable homes a year for ten years, in a contribution to the government’s National Housing and Homelessness Plan.

This far exceeds the Housing Australia Future Fund’s $10 billion promise of 30,000 new social and affordable homes over five years.

“The structural failures and policy gaps, especially in housing affordability and support for vulnerable people, are leaving more people in a strained system,” Ms Colvin said.

Homelessness Australia argued that 500,000 new social and affordable homes could solve homelessness within ten years, along with more generous Commonwealth Rent Assistance.

e61 Institute research manager Nicholas Garvin said strong population growth was driving up house prices, especially when there was a housing shortage.

“Demand for housing in Australia tends to continually grow due to population and income growth, which in itself pushes up prices if housing supply does not keep pace,” he said.

In the year to August, 413,530 permanent and long-term migrants arrived in Australia (pictured are new homes in Oran Park in Sydney’s far south west)

But only 168,231 private homes – both houses and units – were built in the last financial year

“Supply skeptics may observe these rising prices, alongside supply rising but not as fast as demand, and not realize that prices would rise even faster if supply did not grow at all.”

But if population growth were to outpace supply, prices would continue to rise, especially in Sydney.

“All postcodes saw positive price growth during this period, so many people would have observed rising prices as housing supply grew,” Mr Garvin said.

Sydney house prices have risen 8.1 per cent to $1.381 million over the past year, despite 12 rate hikes by the Reserve Bank since May 2022, CoreLogic data shows.

The large influx of international students has also led to an annual increase in rents of 18.2 percent to $672 per week, data from SQM Research shows.

The rental vacancy rate in Sydney was 1.3 percent in September, lower than the 1.5 percent of a year earlier.