Were there only SIX Wonders of the World? Historian Bettany Hughes explores the continued fascination the ancient mysteries hold for us

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

by Bettany Hughes (W&N £25, 416pp)

An aproto-science fiction story by the 2nd century AD Greek writer Lucian of Samosata has its hero traveling to the moon. Looking down, he can only recognize Earth when he sees two of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World: the Colossus of Rhodes and the Pharos Lighthouse.

Despite the fact that only one Wonder – the Great Pyramid of Giza – remains more or less intact, they still mean something today. In this deeply researched book, historian and TV documentary maker Bettany Hughes explores the fascination that these ‘brilliant adventures of the mind’ continue to hold for us.

There have been several slightly different lists over the centuries, but Hughes’s book focuses on what might be called the canonical seven, the lists most often cited. The first and oldest is the Great Pyramid, built as a tomb for the Egyptian pharaoh Khufu in the 26th century BC. Those who worked on it had to lift a block of limestone every two to three minutes, ten hours a day for at least 24 years.

The legendary Colossus of Rhodes, one of the Seven Wonders, was a lighthouse in the shape of a statue of the god Helios

And how wonderful, she speculates, would have been the treasures buried with Khufu. They are all long gone, looted by grave robbers, but they must have been much better than what was found in the burial chamber of Tutankhamun, a relatively unimportant pharaoh.

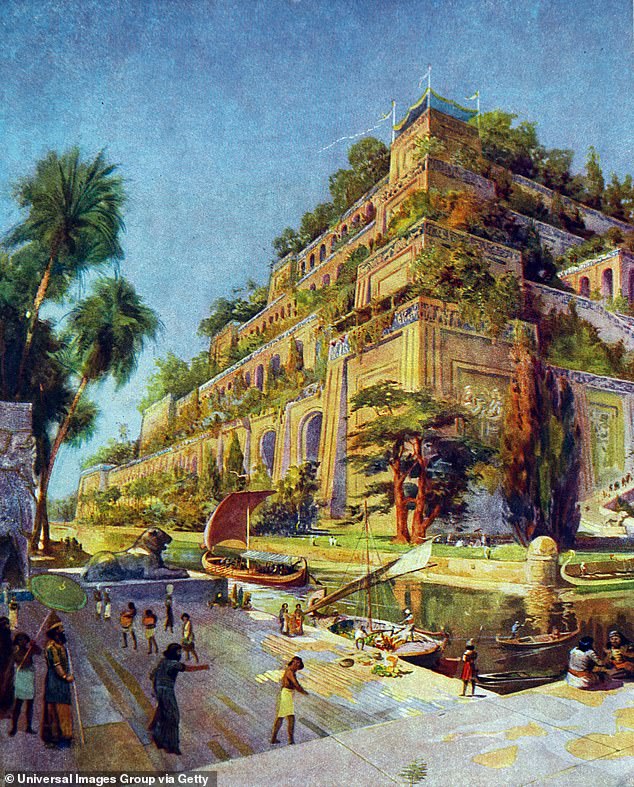

The second miracle may not have even existed. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon are still famous, but there is very little evidence that they were real. Neither Xenophon nor Herodotus, two ancient Greek historians who almost certainly visited Babylon, mention them. Some scholars now argue that, if they existed, they were not in Babylon, but in Nineveh, the capital of the Assyrian Empire.

There is no doubt about the reality of the other miracles. “The sun has never shone on anything like it,” wrote a visitor to the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus. Said to be the largest building in the ancient world, twice the size of the Parthenon, it was destroyed and rebuilt several times.

One of its patrons was Croesus, a man so wealthy that his name is still synonymous with fantastic wealth.

It remained a tourist attraction for almost a millennium. Visitors could buy mini temples of Artemis, just as you can get mini Big Bens in London today.

Size was important to the ancients. The statue of Zeus at Olympia, the only wonder in mainland Greece, was as tall as a three-story house.

Its creator, Pheidias, is said to have asked the king of the gods for his approval when it was finished. Zeus sent down a bolt of lightning. (How he would have reacted differently if he had disapproved is not clear.)

Pheidias may also have used the image to confess his crush on a famous athlete. It was said that ‘Pantarkes is beautiful’ was engraved on the finger of Zeus.

Only one wonder – the Great Pyramid of Giza – remains more or less intact

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon are still famous, but there is very little evidence that they were real

The tomb of Mausolus, ruler of Karia in what is now southwestern Turkey, was so impressive that it merited mention as a miracle. Within a few years of the man’s death in 353 BC it was reopened and plundered, but his name lives on. We still call a grand example of funerary architecture a ‘mausoleum’.

Another wonder, the Colossus of Rhodes, was, in Hughes’ words, “legendary within weeks of its completion.”

Standing over 100 feet tall, with an iron skeleton and bronze skin, it stood guard over the island for only 60 years before it was toppled by an earthquake. An earthquake also created the last Wonder, the Pharos Lighthouse in Alexandria, long the second tallest structure in the world. It finally fell in 1303 AD, almost 1,500 years after it was built.

Hughes has written a richly detailed guide that offers many insights into what the Miracles meant to people in the ancient world, and what they can and do for us today.