Warning that rise in childhood obesity caused by Covid could cost society £8 BILLION – with one in five children now fat by the time they reach secondary school

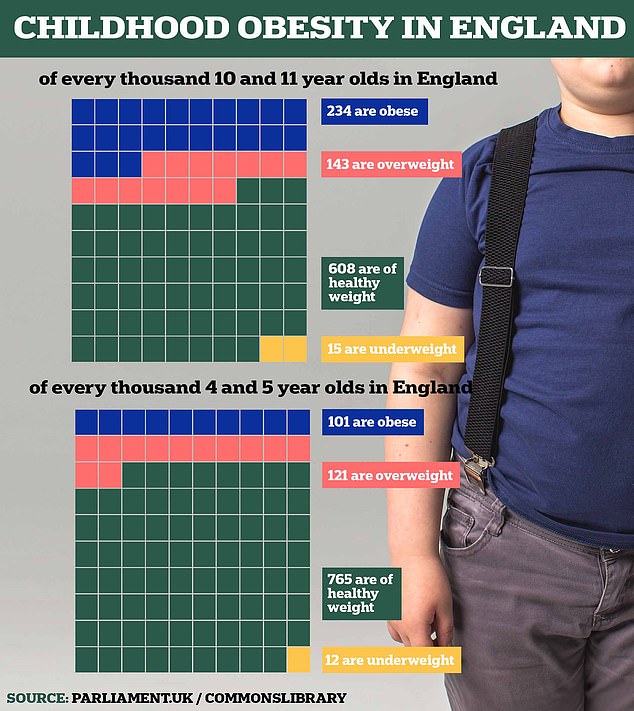

More than one in five 10 and 11-year-olds are now classified as obese, official figures show.

Experts have warned that children in year six are to blame for rising rates of childhood obesity caused by the Covid pandemic.

Analysis shows that there are 56,000 more overweight or obese children in this age category than there should be.

And as well as having a ‘profound’ impact on children’s development, it could cost wider society more than £8 billion, according to predictions.

Researchers from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), Southampton Biomedical Research Center and the University of Southampton analyzed more than one million children in England.

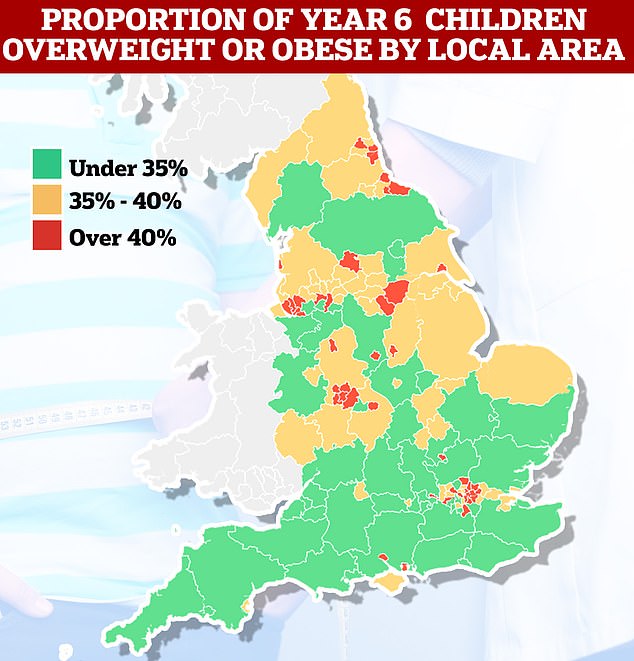

More than a million children had their height and weight measured as part of the National Child Measurement Program (NCMP). Nationally, the rate among children in the sixth form is over a third, despite falling slightly since the start of Covid

Among sixth grade students, national obesity decreased from 23.4 percent in 2021/2022 to 22.7 percent. Meanwhile, the proportion of children considered overweight or obese also fell from 37.8 percent to 36.6 percent. Both measures are above pre-pandemic levels

They used data from the National Childhood Measurement Program (NCMP) to calculate the increase in childhood obesity, focusing specifically on the BMI of children in care – aged four to five – and who in year six were between 10 and 11 years old.

Analyzes showed that childhood obesity rose dramatically between 2020 and 2021.

The biggest jump was recorded among reception-age pupils, where obesity rose by 45 per cent.

The team attributed this to a change in young people’s eating habits and activity levels during lockdown, when most were educated from home.

Organized sports and recreational activities were largely unavailable, and there were knock-on effects on children’s sleep schedules and screen time.

The data showed that by 2022, the number of obese four- and five-year-olds had returned to pre-pandemic levels, suggesting that weight gain at this age may be reversible.

But the number of 10- and 11-year-olds overweight or obese remained higher than expected (23.4 percent), amounting to around 56,000 additional children.

The scientists warned that costs will rise because overweight and obese children and teenagers often become obese adults.

This includes the money the NHS spends on treating the complications of obesity, such as type 2 diabetes, heart disease and some cancers, and the fact that obese people are more likely to die early.

Writing in the journal PLOS One, the team said: ‘During 2020-2021 there were steep increases in the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children.

‘In 2022, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children aged four to five years returned to expected levels based on pre-pandemic trends.

‘However, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children aged 10 to 11 years persisted and was four percentage points higher than expected, representing almost 56,000 additional children.

‘The additional lifetime healthcare costs in this cohort will be £800 million, with a cost to society of £8.7 billion.’

Professor Keith Godfrey, one of the study’s authors, said: ‘The increase in childhood obesity during the pandemic illustrates its profound impact on child development.

‘Our projection that this will result in over £8.7 billion in additional healthcare, economic and wider social costs is hugely worrying.

‘In addition to the even higher costs of the ongoing childhood obesity epidemic, it is clear that we need more radical new policy measures. This will help reduce obesity and secure well-being and prosperity for the country as a whole.”

The researchers also found that children living in the most deprived areas of England are twice as likely to become obese compared to children living in the least deprived areas.

This means they will face higher lifetime economic costs compared to wealthier populations.

Co-author Professor Neena Modi, from Imperial College London, said: ‘Obesity disproportionately affects children living in deprived communities – and the gap between the most and least deprived groups has widened over the past decade.

‘We need targeted interventions to close this alarming gap, especially in children under five, where our research shows overweight and obesity are most easily reversed. This way, every child has an equal chance to grow up healthy.’

The number of obese children is increasing enormously; one in ten children in the Reception year at school are now considered obese. Data for 2021/22

Meanwhile, Professor Simon Kenny, NHS England’s national clinical director for children and young people, said: ‘These figures will be as alarming for parents as they are for the NHS.

‘Obesity affects every human organ system and so can have a major impact on a child’s life at a young age, increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes, cancer, mental health problems and many other diseases, which can lead to shorter and more unhappy lives. .

‘The NHS is committed to helping as many young people and families with weight problems as possible through our new network of 30 specialist clinics, offering tailored packages of physical, psychological and social support.

‘But the NHS cannot solve this problem alone, and continued collective action from industry, local and national government and wider society is needed if we are to avoid a ticking health time bomb for the future.’

Commenting on the research, Councilor David Fothergill, Chair of the Local Government Association’s Community Wellbeing Board, added: ‘Childhood obesity is one of the biggest public health challenges we face.

‘Municipalities across the country are working hard to make a local impact, but the challenge is significant because the causes of unhealthy weight are complex, long-term and interconnected.

‘Councils are spending significant amounts of time, effort and money on a range of measures to combat the problem.

‘Unhealthy weight is not just a public health problem, it is a problem for everyone and extends to all areas of responsibility of the municipality.’