US becomes first country in the world to approve gamechanger Alzheimer’s drug lecanemab

>

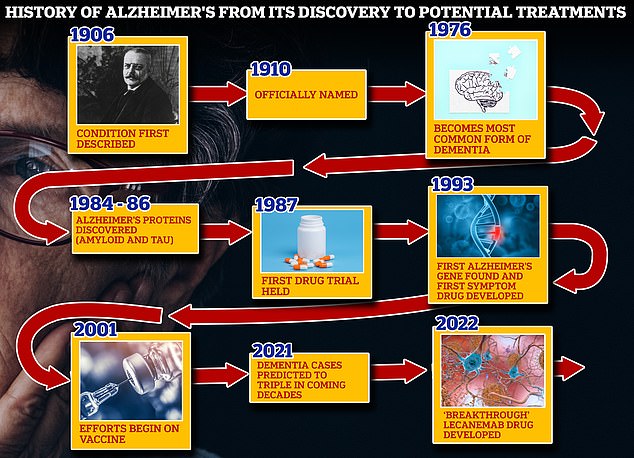

US health officials today approved the first Alzheimer’s drug shown to slow the condition, in what could be a breakthrough for millions of patients.

Lecanemab, to be sold under the brand name Leqembi, instantly becomes the most effective treatment on the market after receiving accelerated approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on Friday.

The drug, given every two weeks as an intravenous infusion, was shown to slow the progression of cognitive decline by 27 percent in early-stage Alzheimer’s patients compared to a control group.

Experts told DailyMail.com the approval was a ‘historic’ moment, but raised concerns about how many people will access the drug, which will cost around $26,500 a year.

The FDA has approved the new Alzheimer’s drug, lecanemab, from Eisai and Biogen, for use in early- and mid-stage patients. Slowed disease progression by 27 percent over 18 months in clinical trials (file photo)

“Alzheimer’s disease greatly disables the lives of those who suffer from it and has devastating effects on their loved ones,” said Dr. Billy Dunn, who works in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in a statement.

“This treatment option is the latest therapy to target and affect the underlying disease process of Alzheimer’s disease, rather than just treating the symptoms of the disease.”

The development and research of the drug was carried out by the company Eisai, based in Tokyo, Japan. It partnered with Biogen, of Cambridge, Massachusetts, for its commercialization.

Once approved, the FDA recommended that the drug be used in patients who are in the early and middle stages of Alzheimer’s disease. This includes at least 1.5 million of the 6.5 million Americans diagnosed with the condition.

Phase III clinical trials included 1,795 patients with early Alzheimer’s. Half of the participants received 10 mg/kg of the drug every two weeks. Instead, the other group was given a placebo.

The researchers measured the participants’ memory, judgment and problem-solving abilities before the trial began and again at 18 months.

They found that those taking the drug saw their cognitive state deteriorate at a rate 27 percent slower than the placebo.

“Trial data have shown that lecanemab has a small but measurable impact on slowing the progression of Alzheimer’s disease,” Hillary Evans, executive chef at Alzheimer’s Research UK, said in a statement.

“In practice, the benefits of lecanemab are likely to be measured in additional months rather than years. However, as anyone affected by Alzheimer’s disease knows, this time can be precious.

UK regulators are expected to authorize the drug for use this year.

However, it came with some dangers. One in eight participants using lecanemab experienced brain swelling, compared with one in fifty members of the control group.

However, these cases were not symptomatic, according to the pair of firms behind the drug.

Microbleeds, or small spurts of bleeding in the brain, were twice as common in the lecanemab group as in the placebo group, with 17 percent suffering from the problem.

The drug’s label will also include warnings against using blood thinners while using lecanemab, a known risk of drugs that fight amyloid-beta plaques in the brain.

Two of the three patients who died in the clinical trials after experiencing brain hemorrhage and inflammation were also being treated with blood thinners.

The deaths occurred at the end of the trial, at a point when they knew they were being treated with the drug and not a placebo.

However, the promising trials have many experts excited. There are currently no effective treatments for Alzheimer’s itself, and doctors generally only help patients manage symptoms as they continue to decline.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, which assesses the value of drugs, said the value of the drug ranges from $8,500 to $20,600 a year. This makes the price of $26,500 set by Eisai an oversold.

Last year, the FDA approved Aduhelm for the treatment of Alzheimer’s. The controversial approval was widely criticized by experts after the dubious results in the trials.

That drug targeted amyloid plaques in the brain that had already formed. It is believed that the formation of these deposits in the brain are responsible for cognitive decline.

Instead, Lecanemab targets the proteins that make up these plaque deposits before they clump together, making experts hopeful that it will be more effective than its predecessor.

Still, the Aduhelm debacle has left a sour taste in the mouths of some Americans.

A congressional investigation revealed last week that the drug’s approval process was “rife with irregularities.”

“The findings of this report raise serious concerns about the FDA’s protocol flaws and Biogen’s disregard for efficacy and access in the Aduhelm approval process,” the report, prepared by the staff of the Committee on House Oversight and Reform and the House Power and Energy Committee. Trade, concluded.