Unraveling the mystery of the world’s oldest tattoos: Ötzi the iceman applied his own ink 5,300 years ago using a puncture technique, research shows

He died more than 5,000 years ago, shot in the back with an arrow by a mysterious assailant in the icy Alps.

But Ötzi the Iceman, Europe’s oldest mummy, continues to reveal secrets today, thanks to the numerous tattoos on his withered body.

Despite the fact that he lived between 3350 and 3105 BC, scientists in Tennessee claim to have solved the mystery of how these tattoos were made.

They say the tattoos were likely made by Ötzi himself using a technique known as “hand poking,” in which a sharp hand tool repeatedly punctures the skin.

One of the experts tattooed himself using several ancient techniques to figure out which one produced the markings that most resembled the iceman’s.

Ötzi the Iceman is the natural mummy of a man who lived between 3350 and 3105 BC. Ötzi’s remains were discovered in the Ötztal Alps on September 19, 1991

Ötzi presents some of the earliest direct evidence of tattooing in the human past, they say in their new study, published in the European Journal of Archaeology.

The old male had a total of 61 tattoos, consisting of 19 groups of black lines, most of which were less than an inch long.

Despite decades of research, it was until now unclear how the iceman tattoos were made and what tools and methods were used.

Popular discussions describe his tattoos as being made using an ‘incision technique’, which involves first cutting the skin and then rubbing in vegetable pigment.

But researchers from the Tennessee Division of Archeology (TDOA) are now questioning this, claiming instead that a “hand-poking” technique was used.

Here the sharp object is dipped into the tattoo ink and then inserted point by point into the skin.

“Early discussion of the iceman’s marks suggested that they were not traditional tattoos, but sites where plant material had been packed into incised wounds and then set on fire,” TDOA archaeologist Aaron Deter-Wolf said. ScienceAlert.

“There’s absolutely no evidence of that, and over time the bit about fire was left behind, but the idea that they were cut up persisted.

Reproduction of Oetzi the Similaun man in the South Tyrolean Archeology Museum in Bolzano, South Tyrol, Italy

The mummified, 5,300-year-old corpse was found by hikers in 1991, melting from the ice in the Alps, some 3,210 meters above sea level

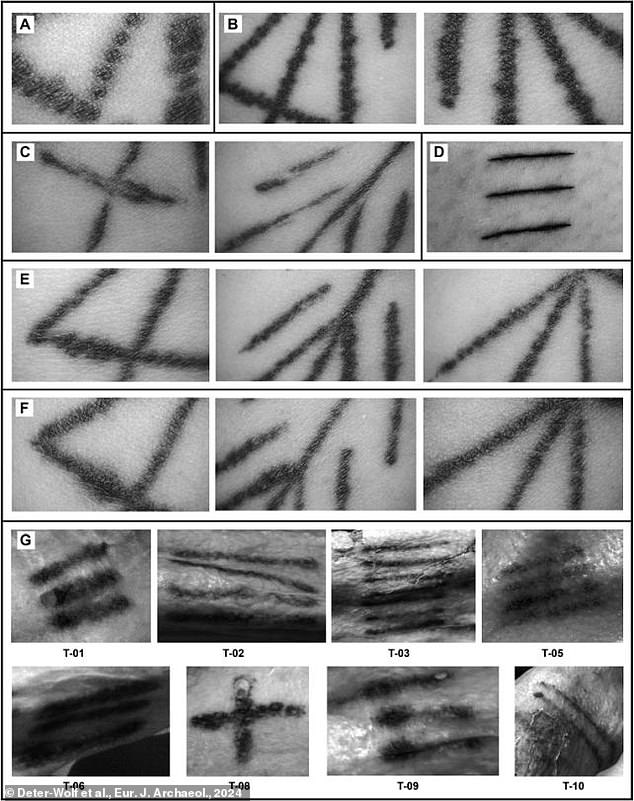

The experts tattooed themselves using multiple age-old techniques to find out which one yielded the markings most similar to the Iceman’s

“Most archaeologists who have discussed Ötzi’s tattoos in recent years honestly say that we don’t know how they were made, but the idea still pops up in virtually every popular media discussion.”

Deter-Wolf teamed up with tattoo artist Danny Riday of New Zealand’s Temple Tattoo to reveal more about how Ötzi got his tattoos.

Using four different tattoo techniques, they replicated Ötzi’s tattoos on Riday’s leg, allowed them to heal and then compared them to the old originals.

“Every time a tattoo instrument breaks the skin, a small wound is created, and all wounds have distinctive properties that depend on how they were created,” Deter-Wolf said.

While the incision technique produces straight, clean edges of the blade, the manual puncture technique results in small overlapping circles or irregular shapes.

The team found that the iceman’s incisions were most similar to the latter and were likely made with a shaped bone or a copper awl, a small pointed tool.

Using four different tattoo techniques, they replicated Ötzi’s tattoos on Danny Riday’s leg. allowed them to cure and then compared them to the old originals. Pictured: Tattoos on Riday’s leg on the day they were made (left) and six months later (right)

Comparison of tattoos on Riday (AF) with tattoos on Ötzi (G) suggested that the iceman used the ‘hand poking’ technique

Deter-Wolf told ScienceAlert that these types of artifacts appear in the archaeological archive of the Ötzi Alps, where his mummified body was found.

None have ever been identified as a tattooing tool, but the team’s new study may prompt archaeologists to reassess what they were used for.

Ötzi’s frozen body was found, accompanied by his clothing, equipment and an abundance of plant and fungal spores preserved on his clothing and in his intestines.

High in the Italian Alps 5,300 years ago, Ötzi, the iceman, was shot in the back with an arrow and probably bled to death within minutes.

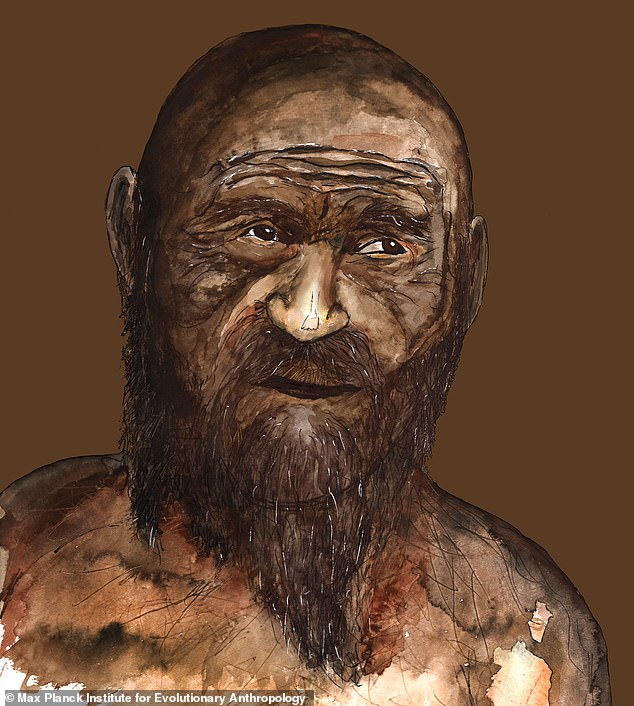

On top of this discovery, the researchers discovered that Ötzi was descended from early farmers who migrated from Anatolia. Pictured is an artist’s impression of what experts think he looked like

After collapsing into the ice, his body was preserved until it was discovered in 1991, making him the oldest mummy in Europe.

Since then, mystery and intrigue have ensued, including investigation into who might have killed him, and new secrets continue to be unlocked.

Last year, another team of scientists announced that Ötzi had dark skin, dark eyes and a bald head, and not blond and hairy as previously thought.

On top of this discovery, the researchers discovered that Ötzi was descended from early farmers who migrated from Anatolia.

A 2018 investigation into his remains concluded that an arrow dealt Ötzi a fatal blow by severing the nerve of his shoulder and hitting his major blood vessels.