UK mums are OLDER than ever

>

Mothers in England and Wales are older than ever before, official figures revealed today.

With more and more women choosing to put off having children until later in life in pursuit of a career, the age of giving birth hit 30.9 in 2021.

Data from the Office of National Statistics — which goes back until before WWII —shows this is nearly five years older than in the 1970s.

Britain’s birth rate has also fallen even more than previously estimated and now sits at a record low.

The rise of the older mum. Data from the Office of National Statistics (ONS)shows the average age of mothers in England and Wales has increased since the 1970s, now reaching 30.9 years as of the latest figures

The ONS report on births for 2021 shows the average age of mothers in England and Wales is now 30.9 years.

It marks the oldest British mothers have ever been on average and is part of a steady increase in average birth age since 1973.

In that year, the average age of British mothers was just 26.4 years.

Births in women over the age of 40 now double those of teenagers.

Yet just five decades ago, there were nine times as many teenage mothers having babies as those over 40.

The rising average age of mothers has been linked to women choosing to pursue careers over starting a family in their twenties, as well as financial pressures like the cost of childcare.

Medical advances such as IVF have also made becoming a mother later in life more possible, though this is not always a guarantee, and can be expensive.

But doctors tend to warn women not to leave it too late to have children. They stress that with age fertility drops and their risk of complications, including stillbirths, increases.

Experts estimate women in their late forties have as little as a one in 20 chance of becoming pregnant because of their lower supply of eggs, which are less capable of being fertilised.

The British Fertility Society previously warned celebrities who have children in their 40s are giving women false hope about late motherhood.

British fathers have also got progressively older, although the change hasn’t been so dramatic.

Fathers in England and Wales were 33.7 years old on average in 2021, about four years older than 1974, when the average age was just 29.4 years.

The ONS data also shows the overall total fertility rate for England and Wales has also dropped to its lowest ever recorded level of 1.55 children per woman in 2021.

This figure represents the average number of babies each woman is expected to have on average over the course of her life.

A rate of 2.1 is generally considered to be a replacement level, i.e., the number of children needed for the population to maintain its current numbers without additional factors like migration.

Meghan Markle, the Duchess of Sussex, pictured here in 2019 while pregnant with her first child Archie, is classified as an older mother, having given birth to her son when she was 37, and then to her daughter Lilibet when she was 39

The ONS had previously calculated the 2021’s fertility rate to be 1.61 children per woman but revised it down following more accurate data from that year’s Census.

It follows a steady decline in the total fertility rate for England and Wales, with 2020’s figure being 1.58.

The last time the fertility rate was above the replacement of 2.1 was 1972 when it was 2.7 children per woman over the course of her life.

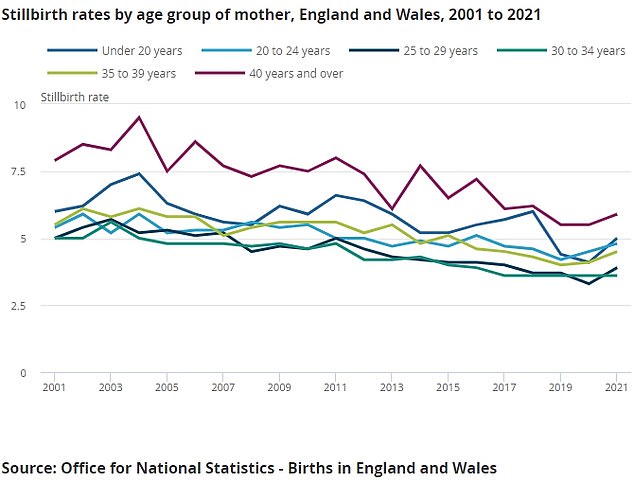

While total birth rates have declined, sadly the rate of babies born dead has gone up.

England and Wales recorded 4.1 stillbirths, when a baby is born dead after 24 completed weeks of pregnancy, per 1,000 births.

The figure reverses two years in the overall decline in the rate of stillbirths.

In 2020 the ONS recorded the lowest ever rate of stillbirths England and Wales, at just 3.8 per 1,000 births.

While almost all age groups saw a rise in stillbirth rates the highest rate was in the very oldest mothers, the 40-years and over group, who experienced 5.9 stillbirths per 1,000 births.

This was up from 5.5 stillbirths per 1,000 births in 2020.

The second highest rate was among teenage mothers, at five stillbirths per 1,000 births, up from 4.1 in 2020.

Mothers aged 30-to-34-years-old were the only group to not see a rise in stillbirth rate, maintaining a value of 3.6 per 1,000 births, the same figure as the year prior.

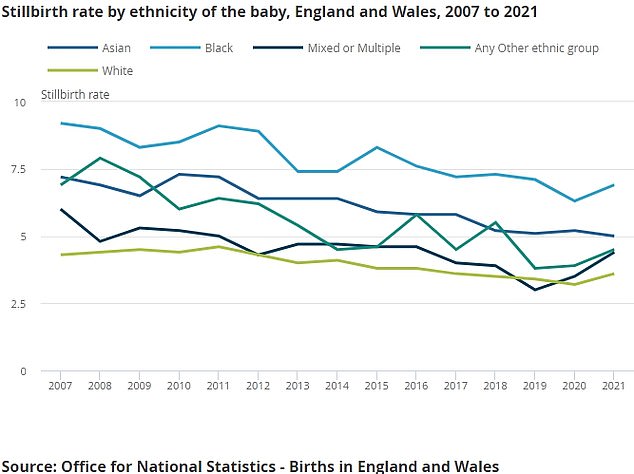

Black mothers were the most likely ethnicity to suffer a stillbirth in England and Wales, with a stillbirth rate of 6.9 per 1,000 births, essentially double that of White mothers who had a stillbirth rate of 3.5 per 1,000 births.

The ONS data also shows that stillbirth rates have gone up in the latest round of data, a reversal of a previous decline

The risk of stillbirth was highest among Black mothers, with a rate of 6.9 per 1,000 births, essentially double that of White mothers who had a stillbirth rate of 3.5 per 1,000 births

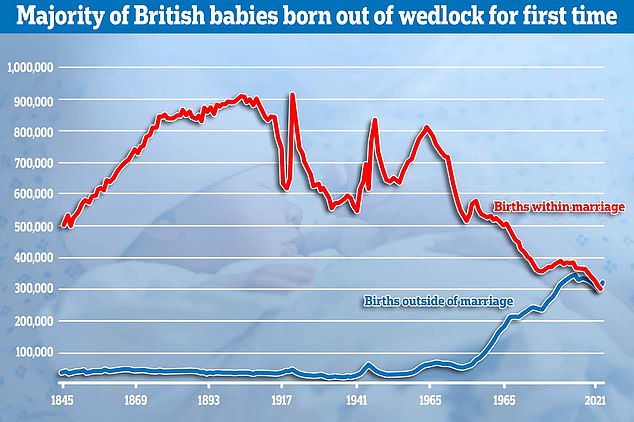

More babies were born outside of marriage in England and Wales in 2021 than to wedded couples for the first time on record, official figures show. The latest Office for National Statistics data shows around 625,000 live births were logged in the two nations in 2021. But 321,000 of these were outside of marriage or a civil partnership, while 304,000 were within one

A similar gap was seen in terms of wealth.

The stillbirth rate in the 10 per cent most deprived areas of England was 5.6 per 1,000 births, more than double the rate in the 10 per cent wealthiest areas of the country which only recorded 2.7 stillbirths per 1,000 births.

Stillbirth support charities Sand’s and Tommy’s said the figures required swift and strong action to support pregnant women in the UK from all backgrounds.

Rob Wilson, head of the Sands & Tommy’s joint policy unit said: ‘Stronger action is required from government both within and outside of the health service to improve outcomes and address persistent inequalities by ethnicity and deprivation.’

‘We know from our own work at Tommy’s and Sands that people can face a range of barriers to accessing maternity services, and that there is variation in people’s experience of care.’

With a nod to the current pressures the NHS is under, Mr Wilson added that the Government needed to do more ensure maternity services were safe.

‘Maternity services are currently under substantial pressure,’ he said.

‘It is important that government provides the workforce and funding needed to deliver safe and equitable care, to ensure the best possible outcomes for all.’

Today’s ONS data also confirmed previous analysis that 2021 saw more babies born outside of marriage in England and Wales than to wedded couples for the first time on record.