Trendy quartz countertops are causing an ‘epidemic’ of illness, while dozens of others are reporting deadly black lung

Doctors warn of a ‘new and emerging’ epidemic caused by stylish and durable quartz countertops.

The dust released when the stone is cut and inhaled by workers causes irreversible scarring of the lungs, causing patients to suffer from shortness of breath and a painful cough.

This is known as silicosis or ‘black lung’ and is essentially a death sentence unless the person undergoes a lung transplant, which can only allow them to survive for a handful of years.

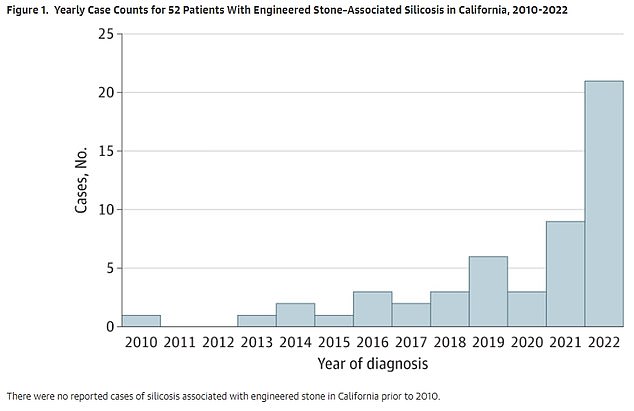

The condition was previously thought to be disappearing, with fewer than five cases per year in California, but since 2019, scientists have recorded at least 70 cases in the state.

Researchers at the University by California, Los Angeleswarn about that A new type of quartz countertop that contains more silica is behind the wave, because it releases more silica dust when it is cut, causing more scarring of the lungs and increasing the risk of disease. They also warn that doctors underdiagnose the condition.

In their study, the scientists found that up to four in five cases of silicosis were missed on the initial examination – with patients more likely to be told they had a lung infection. This delayed critical and potentially life-saving treatment.

They also found that in 48 percent of cases, patients had ‘atypical’ features in their lungs – or shifts that don’t normally show up on scans.

Dr. Sundus Lateef, a radiologist who led the analysis, said: ‘This is a new and emerging epidemic, and we need to raise awareness about this disease process so that we can avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment for our patients.’

Above is Marek Marzec, from Great Britain, who was diagnosed with silicosis at the age of 48. While working as a stonemason, he had worked with quartz countertops for ten years

In the study, presented at the annual conference at the Radiological Society of North America in Chicago, researchers examined the CT scans and pulmonary function tests of 55 workers diagnosed with the disease.

They were all male, Hispanic, approximately 43 years old, and had been exposed to silica dust for an average of 18 years.

All were also symptomatic; most suffered from shortness of breath and/or coughing, and lived in an urban area outside Los Angeles.

In a preliminary analysis of 21 patients, researchers found that only four cases – or 19 percent – were correctly diagnosed on their first visit by primary care physicians.

Among radiologists, they found that only seven patients (33 percent) were correctly diagnosed on their first visit.

In most cases, the researchers found that patients received alternative diagnoses, such as an infection.

The doctors warned that a new type of countertop was responsible for the rise in cases, which is technically called quartz and is made by holding quartz shards together with a resin. It usually contains much more silicon.

Inspections show that more than half of California quartz cutting workplaces exceed the maximum allowable limit for silica dust in the air.

Workers can reduce their exposure by wearing face masks or using a cutting machine that sprays water onto the stone at the same time, preventing silica dust from becoming airborne.

Above you see a quartz worktop in a kitchen. Silicon dust is released during cutting, which can increase the risk of lung disease for workers

The above shows the number of cases per year for patients diagnosed with silicosis. It is based on 52 cases and the graph was published last year

But researchers say many of the workers in these industries are immigrants and Spanish-speaking people, who are vulnerable to exploitation.

Dr. Lateef added: ‘There is a critical lack of exposure and screening for workers in the industrial stone manufacturing industry.

“There needs to be a push for earlier screening and advocacy for this vulnerable population, which in our case were Spanish-speaking immigrant workers.”

It is estimated that more than 2 million U.S. construction workers are exposed to silica dust each year.

Scientists say it poses a risk because of the small particles that become airborne and can be inhaled by workers, causing scarring of the lungs.

The American Lung Association says that after 10 to 30 years of working with the stone, workers may develop nodules in their lungs, which reduce the lungs’ capacity and make it harder for them to breathe.

In severe cases, a condition called Progressive Massic Fibrosis (PMF) can develop, in which extreme scarring stiffens the lungs – which normally move with each breath – making it difficult to breathe.

They also warn that patients may need oxygen and other devices to breathe.

There is no cure for the disease, doctors say, which also increases the risk of other health problems such as tuberculosis, lung cancer and chronic bronchitis.

In a study of 52 cases of silicosis published last year, doctors found that ten patients had died – 20 percent – while 11 were referred for lung transplants, three of whom received them.