These First Nations Aussies say they don’t understand what The Voice is about and have some tough words for Anthony Albanese as they reveal why they will be voting NO

Indigenous Australians have expressed doubts about the Voice to Parliament, saying they distrust the government because of its historical treatment of First Nations people.

The group spoke to NITV’s current affairs program The Point this week from Cummeragunja, in the Yorta Yorta country on the NSW-Victoria border, as part of the programme’s “road trip”.

Australians will be asked on October 14 to vote yes or no on whether to include an Indigenous advisory body in parliament.

“I disagree with the Voice; I think there is a hidden agenda because of so many things that have happened to our people.” an elder narrated the program.

“I’m part of the stolen generation and I just don’t trust the government anymore,” she added.

According to some reports, as many as 100,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were removed from their families between 1905 and 1967 to be reinstated into white society, under government-approved policies.

A First Nations elder from Cummeragunja said she was part of the stolen generation and does not trust the government’s proposal for the Voice

Australians will be asked to vote yes or no on October 14 on enshrining the vote to parliament in the constitution

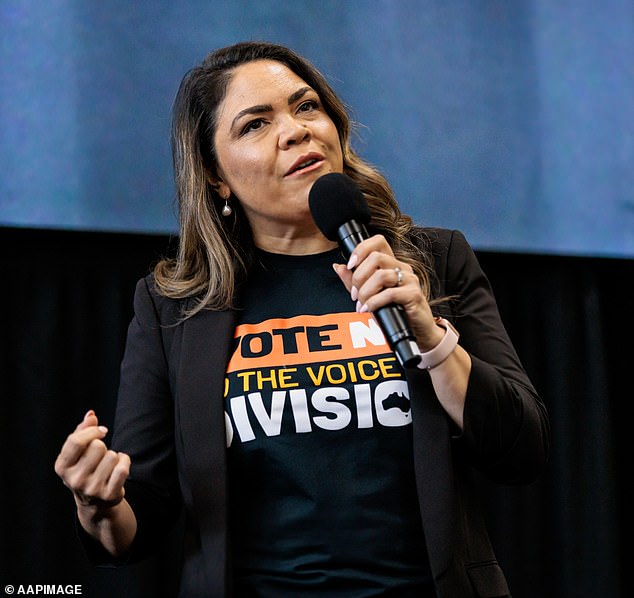

A spokesman for the No campaign, former deputy mayor of Alice Springs and federal senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, has criticized the Voice for being divisive over its intention to create a race-based advisory body in the constitution.

She also claimed that the process from which the proposal emerged, the First Nations Constitutional Convention, was undemocratic and elitist.

“The Uluru Declaration from the Heart was not the result of a constitutional convention open to all Indigenous Australians. The Uluru Dialogues divided the indigenous people for an exclusive talking party for the few, where the few were invited by invitation,” she said.

Her views seemed to be shared by those interviewed in Cummeragunja, a remote community with a history of grassroots activism.

‘I do not understand; I don’t know what it’s going to do for us,” said one woman.

“I just think it should have been explained in more detail. What we get out of it and what that Voice will mean to us.’

A male elder said he was concerned that the Vote would be an ongoing subject for divisive debates, both in Indigenous communities and wider Australia, that could not be removed from the constitution.

“It only makes things worse,” I say. That’s my opinion, everyone has their own opinion.’

While a fourth younger woman interviewed said it’s just not on the radar of people she knows.

‘I don’t really know much about the referendum. No one here really talks about it,” she said.

A First Nations woman from Cummeragunja said she doesn’t understand how the Voice will work or how it will bring about positive change for remote communities, while another says people she knows just don’t even talk about it.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has defended the Voice as coming from Indigenous Australians, not politicians, and as something the vast majority support.

‘The overwhelming majority of the indigenous people want this. All the surveys show somewhere between 80 and 90 per cent of Indigenous Australians support this,” Albanese told Sydney radio station WSFM in June.

He has repeated this claim several times.

The information he refers to comes from two polls conducted earlier this year.

An Ipsos poll in January and a YouGov poll in March showed support for the Voice among First Nations Australians at 80 percent and 83 percent respectively.

Both polls were commissioned by the Uluru Dialogue Group, which supports the Voice proposal.

The Ipsos poll polled 300 First Nations people, with 80 percent saying they would vote yes, 10 percent no, and 10 percent undecided.

The YouGov survey surveyed 738 Indigenous Australians, with 83 per cent saying they would vote yes, 14 per cent saying no and 4 per cent undecided.

Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price has claimed that the Voice proposal grew out of the Uluru Statement of the Heart, which is elitist and not an indigenous indigenous movement.

Mr Albanese said in a speech earlier this year that the Voice would be an opportunity to address the historical treatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

“(It will) be an extraordinary opportunity for every Australian to be counted and heard,” he said.

“After the tumult of colonization, we experienced a lull, a long wave of denial.”

Success requires a majority of Australian voters and a majority of states voting in favour.

If the referendum succeeds, the federal parliament will legislate the details of the vote’s composition, functions, powers and procedures.

Opposition leader Peter Dutton said the government deliberately kept details of the vote secret until after the referendum.

“It’s unknown, divisive and permanent, and I’m convinced that if you don’t understand the details because the Prime Minister is deliberately withholding it from you, you should vote ‘no’,” Dutton said.

It is widely expected that the Liberal leader’s home state of Queensland will vote the majority ‘no’, while ‘yes’ supporters have a strong presence in Albanian’s NSW state.

With Western Australia also tipped to reject the vote, South Australia and Tasmania will become key battlefields for the campaigns.

Volunteers for the Yes and No campaigns mobilize ahead of the referendum (pictured)

Prominent Indigenous advocate and Yes campaigner Noel Pearson was optimistic despite the situation in Queensland and Western Australia.

“We’ve got everything ahead of us, we’ve got a world to win,” Pearson told ABC radio on Thursday.

He said the growing volunteer base would play an important role in the ‘yes’ campaign.

“We’re not going to win this on social media, we’re going to win it at the train stations, in the malls, at the homes of people we knock on,” he said.

Professor Megan Davis, architect of the Uluru Statement from the Heart that led to the referendum, also said that “face-to-face conversations” in communities will be the only path to success.

“What we’ve found in our work is that in areas where indecisive people come in, they’re more likely to leave with a ‘yes’ because they get to know the facts without being constrained by an ideological agenda,” she said.

Early voting for the referendum will begin on Oct. 2, but due to a holiday in the ACT, SA, NSW and Qld, those jurisdictions will open primary elections on Oct. 3.