The US state where meth addicts are being PAID to get sober – as part of $60m taxpayer-funded project

Meth addicts are being paid to kick the habit in drug-ravaged California as part of an experimental new program.

Participants must provide a negative urine sample to prove they are not using meth or crack cocaine, and they will receive a maximum refund of $26.50 per test.

But in a potential loophole, the samples may come back positive for other types of drugs, including opioids like fentanyl and heroin.

The taxpayer-funded project is being implemented in 19 California counties and has enrolled approximately 2,700 drug addicts so far.

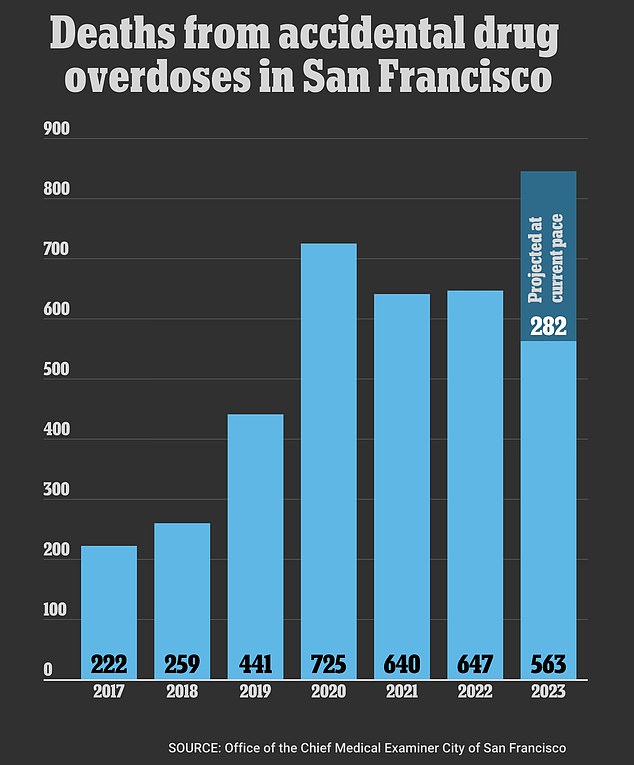

The graph above shows how drug overdose deaths have increased since 2002 and will reach a record high in 2022

A determined deputy collected these shocking before and after mugshots in 2004 to show how meth is plaguing the appearance of addicts in an effort to scare people off the drug

It is funded through Medi-Cal, the taxpayer-funded program for low-income people, and California is expected to allocate $61 million to it.

Program participants admitted that they were initially skeptical of the multimillion-dollar price tag for such an experimental program.

“You’re talking about a lot of money,” John Duff, chief program director at Common Goals, an outpatient drug and alcohol counseling center in Nevada County’s Grass Valley, told the LA times. “It was a hard sell.”

The program is a response to one of America’s worst drug crises. Deaths from cocaine, meth and other stimulants have skyrocketed over the past decade.

In 2021 there were nearly 6,000 opioid-related deaths in California, compared to a total of 80,401 in the US.

In just three years, between 2019 and 2021, opioid-related deaths in California rose 121 percent, according to the state health department. The vast majority of these deaths were linked to fentanyl.

In 2021, 65 percent of drug-related overdose deaths involved stimulants, compared to 22 percent in 2011.

In California’s Sierra Nevada, users say they can get meth almost as easily as beer or weed.

Quinn Coburn is one of the people who enrolled in the new program because he has been using meth for most of his adulthood.

He has been to prison five times for dealing marijuana, methamphetamine and heroin.

Now 56, Mr Coburn wants to quit drugs for good after trying numerous times to kick the habit.

He says the financial experiment is helping. “It’s that little thing that keeps me accountable,” the former construction worker said.

Mr. Coburn wants to stay clean to fight criminal charges for drug and gun possession, which he strongly denies.

He was paid $10 for each clean urine test he returned during his first week in the program.

Above is a man on the streets of San Francisco during America’s drug crisis

Drug addicts and homeless people in the SOMA (South of Market) district, San Francisco

More than 849 people are expected to die from drug overdoses in 2023, which is on pace to exceed the current record of 720 deaths in 2020

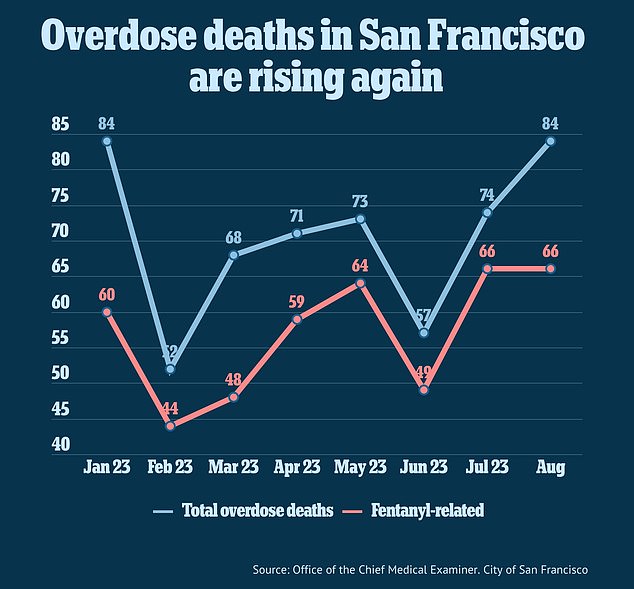

Deaths from fentanyl and other overdoses are again on the rise in San Francisco

The amount per test increases over the week: participants get $11.50 per test in week two, $13 in week three, increasing to $26.50.

Former drug addicts can earn up to $599 per year. Mr. Coburn completed 20 weeks of the program and earned $521.50 by mid-May.

Participants also receive a minimum of six months of additional behavioral treatment after urine testing stops.

California has invested enormous amounts of money and effort into curbing opioid addiction and fentanyl trafficking, but stimulant use is also a major problem.

According to the Department of Healthcare, the number of Californians dying from stimulants doubled between 2019 and 2023.

These photos, taken just three years apart, show how meth use has changed this woman’s appearance in a short time

Pictured three years apart, this woman’s skin is ravaged by her addiction to meth

To qualify for the program, participants must have a moderate to severe stimulant use disorder, with symptoms including strong drug cravings and prioritizing drugs over personal health and well-being.

Experts have said that incentive programs that offer participants a reward, even a modest one, can have a profound effect, especially among meth users.

Previous research has found that such programs can result in long-term abstinence.

Mr Duff, who runs the center where Mr Coburn is being treated, said: ‘The way stimulants work on the brain is different to how opiates or alcohol work on the brain.

“The reward system in the brain is activated more in amphetamine users, so getting $10 or $20 a time is more attractive than being in group therapy.”

He became convinced of the program’s success when users kept coming back with negative urine tests.

“People show up consistently. To get rid of stimulants, it appears to be very effective.’

It is not clear why the urine test should only be free of stimulants so that participants can receive the reward, but it may be that the incentive model is most effective against stimulants, as Mr Duff said.