The Loch Ness monster mystery may finally be solved – scientist claims he has a simple explanation for the mythical beast’s sightings

An expert who has spent fifty years investigating the Nessie phenomenon has delivered his devastating verdict on the monster: that people actually see swans.

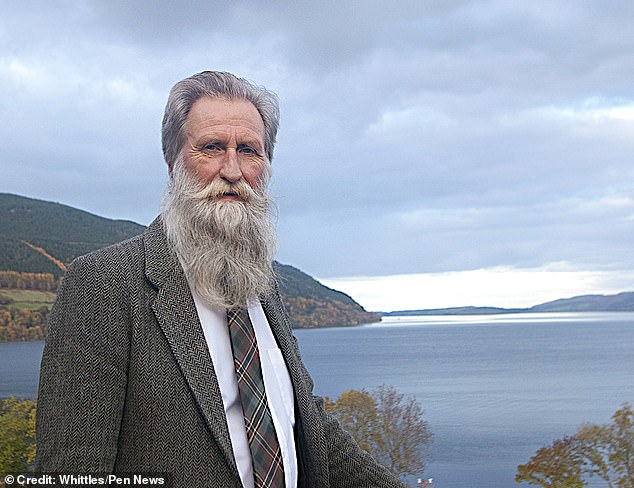

Naturalist Adrian Shine said people who spotted long-necked creatures on Loch Ness were actually misidentifying waterfowl in calm conditions.

While mysterious bumps or loops in the water were actually nothing more than boats waking up, he said, and that’s the “biggest cause of monster sightings.”

He added that the Nessie of the popular imagination was simply the classic sea serpent depicted on old maps in a new inland setting.

Mr Shine, a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and founder of the Loch Ness Project, says he is a “sympathetic skeptic” when it comes to the monster.

But he offered little comfort to those who believe Nessie is real.

He said: ‘Boat wakes are probably the main cause of monster sightings, and waterfowl are the longnecks.’

He continued: ‘Of course there are long-necked creatures on Loch Ness – we call them swans.

An expert who has spent fifty years investigating the Nessie phenomenon has delivered his devastating verdict on the monster: that people actually see swans. Pictured: A composite image of different parts of a swan

Naturalist Adrian Shine said people who spotted long-necked creatures on Loch Ness were misidentifying waterfowl in calm conditions

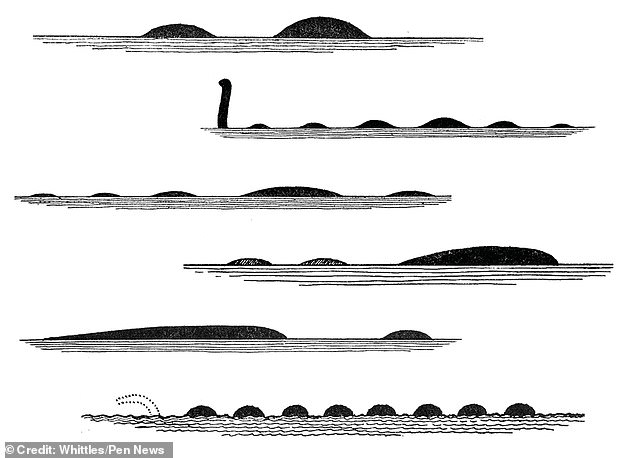

Sketches by various witnesses of their respective sightings of the Loch Ness Monster, published by Nessie researcher Rupert Gould in 1934

“And in calm conditions you can lose your ability to judge distance, and if you can’t judge distance, you can’t judge size.”

He’s not the only one to notice the similarity, either.

Finnish photographer Tommi Vainionpää edited a convincing likeness of Nessie with images of different parts of a swan captured in silhouette.

Other waterfowl mistaken for the monster included cormorants and mergansers, Shine said.

The naturalist, who still lives on the lake at Drumnadrochit, also described how boat wakes could form the classic Nessie humps.

He said: ‘When a ship is coming towards you, it is clear what the wake is – you can see it spreading from the sides of the ship approaching you, or even moving away from you.

‘But when it goes across your front, it’s very different: you see the individual wave train, the individual wavelengths, as solid black bumps.

‘They will be short and many for a slow-moving ship, and they will become longer and fewer as the ship goes faster.

“Of course there are long-necked creatures on Loch Ness – we call them swans,” Mr Shine said.

In his new book, A Natural History of Sea Serpents, Mr Shine explores how the sea serpent of nautical lore was reborn in Loch Ness.

‘The wave lines can be almost continuous, and it is a fascinating illusion. It’s very convincing.’

In his new book, A Natural History of Sea Serpents, Mr Shine explores how the sea serpent of nautical lore was reborn in Loch Ness.

He said: ‘You can’t look at Nessies as a single phenomenon; it is directly derived from the sea serpent controversy.

‘The way it’s perceived… the two forms – the multi-humper and the longnecker – are exactly where the 19th century debate about sea snakes ended up.

‘We know what sea snakes look like, you know it, I know it, everyone else knows it – and the things people are seeing in Loch Ness now will confirm that.

“People will continue to come forward after seeing things they don’t recognize, which will inevitably confirm the stereotypes that society has – this is called confirmation bias.”

As for whether other species could be responsible for the Nessie sightings, Mr Shine characterized the other candidates as a “basket of fish”: sturgeon, catfish and giant eel.

But a 2018 study of the DNA in Loch Ness failed to find any trace of the first two, while the eel DNA discovered could have come from eels of any size.

He said: ‘You can’t talk about Nessies as a single phenomenon – it’s directly derived from the sea snake controversy’

The naturalist added that there simply wasn’t enough food in the lake for a hypothetical monster to survive.

As evidence, he cited the 10% rule, which states that only one-tenth of the energy at any level of the food chain is passed on to the next.

He said: ‘We have measured the open water fish population acoustically and we estimate it to be around 20 tonnes.

“And so if you have twenty tons of fish, you can only have two tons of monster. That would be about half the weight of a basking shark.

“You see the orders of magnitude that we need to achieve, and they are very low.”

In any case, Mr. Shine believes that the Nessie debate will prove more enduring than the issue of sea monsters in the world’s oceans.

He said: ‘The sea is too big for people to really discuss, while the lake represents a finite environment, more amenable to solution.’

He continued: ‘Yes, the lake is quite deep, it’s quite big – it has more water in it than the whole of England and Wales, but it’s still a relatively small place.

‘It is finite and that is why the answer does not seem far away. That’s why it lends itself to the people’s curiosity.’

A Natural History of Sea Serpents is available directly from Amazon or Whittles Publishing for £18.99.