The intriguing way doctors calculate how long patients have left to live – and why they’re often wrong… while MPs vote FOR assisted dying

MPs today took a crucial step towards making assisted dying a reality in England.

The House of Commons has voted in favor of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, which, if passed into law, would give patients with less than six months to live the right to request euthanasia from a medical team.

Although the bill has been passed, it still needs to go through several amendments and more votes in both the House of Commons and the Lords, and even if this goes smoothly, it could still take years before it is actually put into practice.

Debate over the controversial bill continues, including specific concerns about how accurately doctors estimate how long the terminally ill have to live.

Experts have told MailOnline that estimating survival is not an exact science. Some have even compared the reliability of a forecast to that of weather forecasts.

In general, the closer a patient is to death, the more accurate doctors’ predictions become.

This is because certain biological signals, such as a patient’s blood pressure, appetite and clarity, as well as heavy doses of medications such as painkillers, can give doctors a good idea of whether they have days or even just hours left.

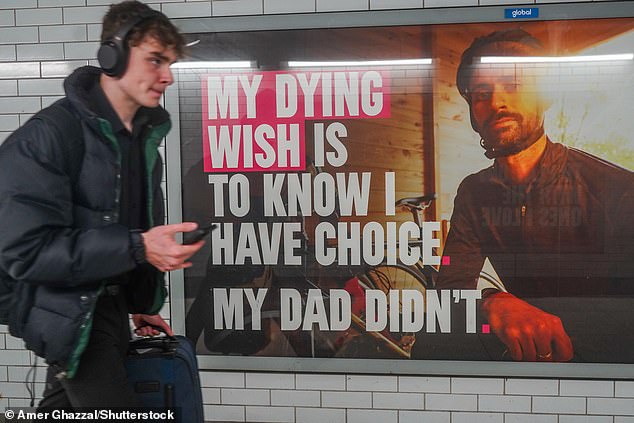

Debate over the controversial bill continues and specific concerns have been raised about how doctors precisely and accurately assess how long the terminally ill should live. Stock image

But when it comes to longer periods, the situation can become more complicated and therefore more uncertain.

Estimates vary by study. Some suggest that clinicians broadly get it right 50 percent of the time, others suggest that this is only a third of the time.

Professor Karol Sikora, a retired oncologist and former director of the World Health Organization’s cancer programme, told this website that the estimates doctors give when patients ask how long they have left are based on population averages of other patients.

These calculations take into account a patient’s specific illness, age, and how serious a condition is.

This means that an older person with multiple tumors will most likely die sooner than a younger person, even at the same stage of cancer.

An important factor to remember is that these estimates are based on averages, meaning there are exceptions at both ends of the scale: some will die sooner than the estimate and others will defy expectations and survive much longer.

Professor Sikora added that the reliability of these estimates can of course vary depending on how common or rare the condition is.

“Of course you could be wrong,” Professor Sikora said.

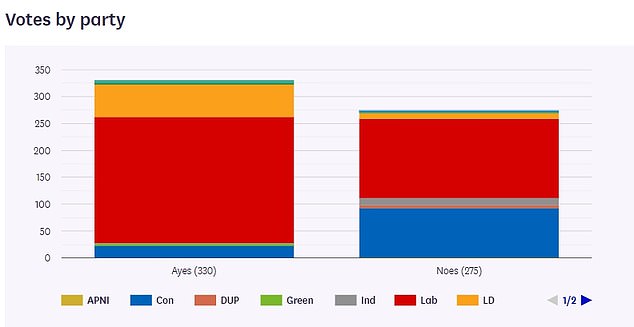

MPs voted in favor of assisted death by 330 to 275, although we won’t know until at least next year whether the bill becomes law.

“It’s a totally inaccurate science.”

Other experts agree. Professor Paddy Stone, former head of Marie Curie’s palliative care research unit at University College London, said there was no estimation method reliable enough to provide a guarantee for assisted mortality.

‘My research shows that there is no reliable way to identify patients who have less than six or twelve months to live…at least, no method that would be reliable enough to act as any form of ‘guarantee’ for the proposed assisted dying legislation. ‘ he said to the Financial times.

Professor Irene Higginson, an expert in palliative care at King’s College London, added: ‘All the research from this country and others shows that estimating the remaining six months is extremely difficult and not very accurate.’

“The science isn’t that well developed yet and I’m not sure it could be because individuals are so different.”

Experts cite studies such as the 2023 one of almost 100,000 patients showing that doctors were right almost three out of four times when estimating whether the patient would die within fourteen days.

They were even more accurate, correct four out of five times, when it came to whether a patient would live longer than a year.

But in the middle period, when a patient still had ‘weeks’ or ‘months’ to go, it was much more difficult; the doctors only succeeded in a third of the cases.

A total of 236 Labor MPs supported the bill, alongside 23 Tories, 61 Liberal Democrats and three Reform MPs from the UK.

Another estimate, calculated by The Telegraphfound that physicians were correct in predicting whether a patient would survive six months in 7,000 cases, but in less than half of the cases.

The uncertainty about the estimates raises concerns that patients who would otherwise live longer could die earlier if they choose assisted death.

Commenting on the data, Professor Katherine Sleeman, a palliative care expert at King’s, said that ‘estimating how long someone has to live is notoriously difficult.’

She added: ‘If a person’s estimated prognosis will be crucial in determining whether he or she is eligible for assisted death, MPs should carefully consider how this estimate will be made, by whom and what is likely to happen. error rate will be.’

Professor Sikora added that another, less scientific factor he had seen during his career was that some patients defy the odds with a specific goal in mind.

“They want to live for a specific reason, for example because their daughter is getting married,” he said.

He recalled a patient in such circumstances who had an expected survival of only a few weeks.

“His daughter was getting married in two months and he just wanted to go to the wedding,” he said.

“He made it to the wedding and died the following Sunday. That was fantastic for him because it was against all odds.”