The Greenland Ice Sheet has lost 1,965 square kilometers of ice since 1985 – an area three times the size of London –

A study shows that the Greenland ice sheet has lost 5,091 square kilometers of ice since 1985.

The world’s second largest ice sheet has shrunk more than three times the size of London and has been collapsing at an accelerating pace since the 1990s.

Researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab found that previous research has underestimated the ice’s retreat by as much as 20 percent.

Their new estimate suggests that 1,034 gigatons, or 1,034 trillion kilograms of ice, have been lost over the past forty years.

The scientists warn that this is enough to risk destabilizing ocean currents, weather patterns, ecosystems and even global food security.

Researchers have found that the Greenland ice sheet has been disappearing at an increasing rate since the 1990s, often culminating in huge icebergs like this one, which broke away from the Jakobshavn Glacier.

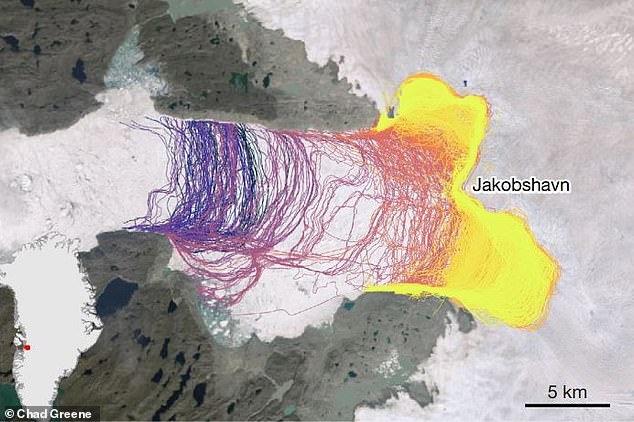

This graph shows how the Jakobshavn Glacier has retreated since 1985. The darker purple colors show the extent of the glacier in the past, while the brighter yellow shows more recent measurements

Researchers analyzed more than 230,000 satellite images of the Greenland ice sheet to measure monthly how the ice sheet has changed.

This new data, published in Naturereveals that every glacier in the ice sheet bar has been losing ice at an increasingly rapid rate since the 1990s.

Despite previously being relatively stable, the ice sheet has shrunk by an average of 218 square kilometers every year since January 2000.

In the most extreme case, the Zachariae Isstrøm Glacier lost 378 square miles (980 square kilometers), or 160 gigatons of ice.

The Jakobshavn Isbræ Glacier, meanwhile, retreated 188 square kilometers, but lost 88 gigatons of ice due to its thickness.

Only Qajuuttap Sermia has grown at all, and this has only gained 1.4 square kilometers of ice.

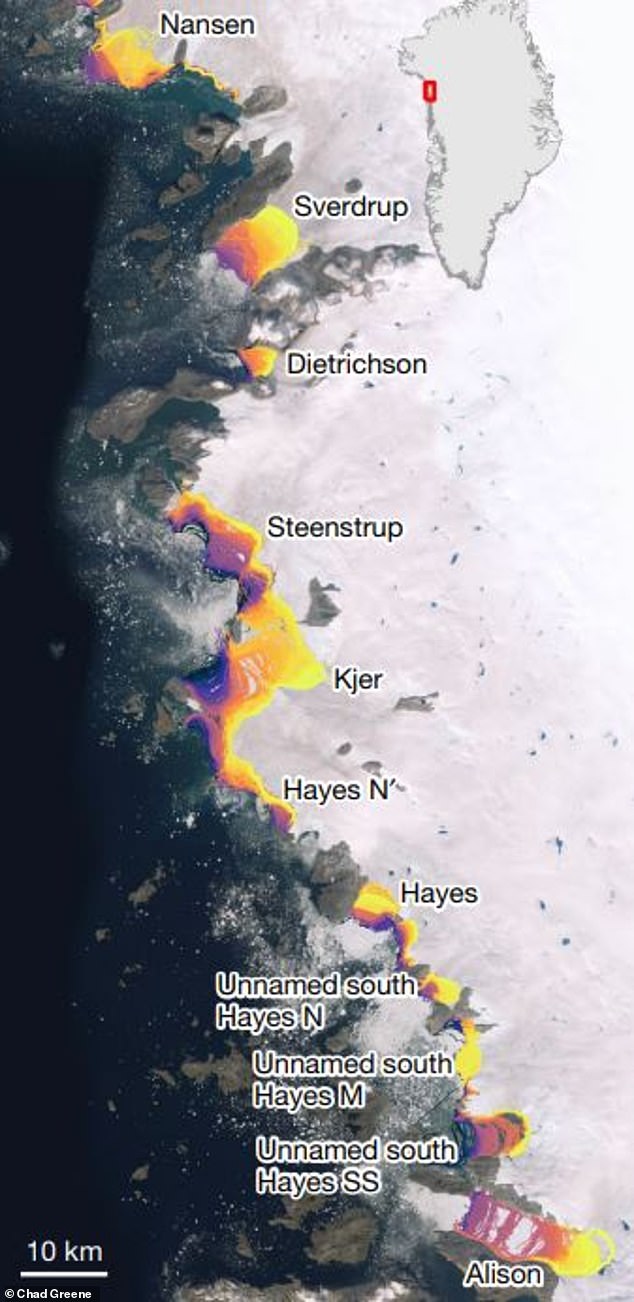

All along the Greenland Ice Sheet, glaciers are moving backward from their older positions (shown in purple) and retreating further inland to their current size (shown in bright yellow)

Chad Greene, a satellite expert at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, found that ice was being lost much faster than previously thought.

Mr Greene and his co-authors write: ‘We report widespread retreat of glacial terminals in Greenland that has resulted in more than 1,000 Gt of ice loss not accounted for in current observation-based estimates.’

They suggest that 43 trillion kilograms of ice are lost every year, which previous measurements have failed to detect.

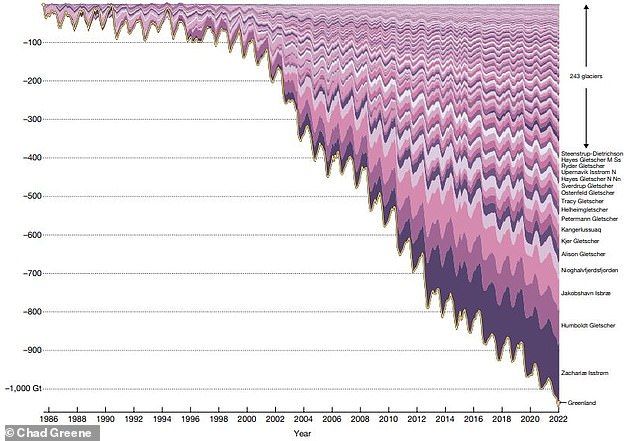

Although glaciers grow in winter and shrink in summer, summer losses have continued to exceed what is regained during the colder months since the 1990s.

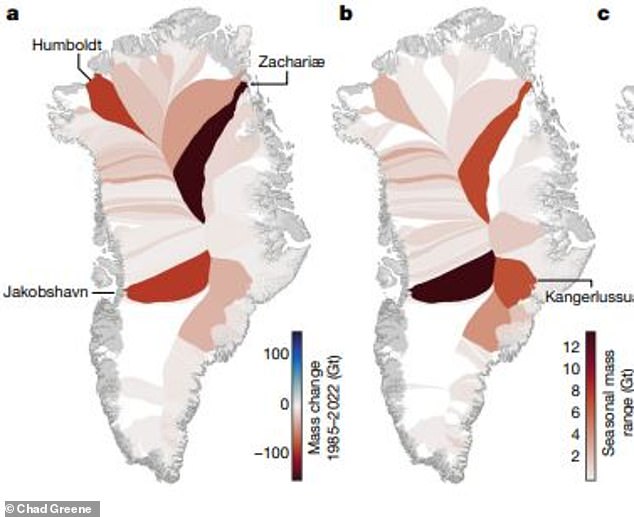

Interestingly, the researchers found that the glaciers that showed the greatest seasonal fluctuations also retreated the most over the past four decades.

They suggest that seasonal variation could be a good predictor of longer-term withdrawal.

For example, Jakobshavn Isbræ gains almost 14 gigatons of ice each winter, but has the second largest total mass loss.

Rising global temperatures due to climate change are the main reason the Greenland ice sheet is shrinking faster every year.

This graph shows the cumulative mass change caused by glacier retreat since 1985. The glaciers have grown and shrunk with the seasons, but overall have been losing mass at an increasingly rapid rate.

Between 2001 and 2011, the Greenland ice sheet experienced its warmest decade in a thousand years.

At high altitudes, temperatures were 1.5°C warmer than in the 20th century.

Last year, scientists from the British Antarctic Survey warned that humans “may have lost control of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet due to climate change.”

Dr. Greene says his research is a measure of how sensitive the Greenland ice sheet may be to future climate change.

These graphs show how much ice has been lost since 1985 (left) and how much seasonal variation is (right) on each glacier. The glaciers with the greatest seasonal changes (represented by darker colors) have also lost the most mass overall

While the collapse of the Greenland ice sheet is unlikely to contribute much to sea level rise, the bigger concern is that it could affect ocean currents.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is a major system of ocean currents that circulates water from north to south.

As warm water flows north, it cools and becomes saltier, becoming compact enough to sink deep into the ocean.

As it falls, the cold water pulls more water behind it before heating up and rising back to the surface, creating a current that moves like a conveyor belt.

But when fresh water from land melts into the sea, it becomes less salty and thus not dense enough to sink.

The concern is that if too much of the Greenland ice sheet melts, the seas will no longer be salty enough to power the currents.

The researchers concluded: ‘There is some concern that any small source of freshwater could serve as a ‘tipping point’ that could trigger a complete collapse of the AMOC, disrupting global weather patterns, ecosystems and global food security.’