The gambling industry rakes in £15 billion a year, but regulator Andrew Rhodes says he is relaxed

Gokman: Andrew Rhodes’ interest in gambling has become ‘more professional’ since he became boss of the gambling watchdog

Andrew Rhodes likes to flutter. The boss of the Gambling Commission – which oversees bookies, casinos, arcades and the National Lottery – has just had ‘a bit’ of success at Cheltenham, bagging two winners on the opening day.

He did not attend the popular horse racing festival, even though many of the horse races he arranges were in attendance at the weeklong jamboree. He didn’t watch it on TV from his office in Birmingham either. He’s too busy for that. But Rhodes, 47, makes no secret of his passion for punting.

“I’m not a big gambler, but it’s something I’ve been doing for a long time,” he says in his lilting Welsh accent. “I’ll never be able to make a living from it, but I’m quite successful.”

His interest in gambling has become more ‘professional’ since he became CEO of the gambling watchdog two years ago.

He cannot play the National Lottery due to his role in granting and managing the license that the Czech company Allwyn has just acquired from Camelot. He can’t even gamble in betting shops or play slot machines.

‘There’s often a sad scene on the South Wales coast, where my kids might be sitting on the 2p machines and Dad is sitting outside on a bench like he’s some kind of miscreant.’

His profile with the gambling association also makes him an occasional target. He recalls: ‘I remember going into a William Hill betting shop in Manchester and someone recognized me and attacked me with his opinion. It was unexpected, but we had a nice conversation.’

There would have been a lot to discuss. Bet365 boss Denise Coates has caused a stir after paying herself £271 million – even though the gambling giant made a loss last year. The sector rakes in £15 billion a year, but Rhodes does not see itself as a profits regulator.

‘The industry can make as much as it wants, as long as it is in line with licensing objectives, as long as it does not target vulnerable people, as long as it is not motivated by crime or because the terms are unfair.’

Anti-gambling activists say a lack of regulation has allowed gambling to spread, especially online, leading to rising rates of harm, addiction and even suicide, especially among young people.

MPs recently called for children to be protected from ‘bombardment’ by gambling advertisements on football fields. One study found 7,000 gambling messages on billboards, shirt sponsorships and in TV commercial breaks in six matches during the opening weekend of the season.

The industry disputes any direct link between sports advertising and gambling harm. It is also against affordability checks – the screening of gamblers’ bank accounts for signs of gambling problems. But the government’s gambling strategy outlined last year calls for stricter rules. So where does Rhodes stand?

“Our focus is to ensure that all advertising is ‘responsible’ so that gambling is not presented as ‘a way to solve problems, make money or relieve stress,’ he says. ‘But it is a difficult subject, just like sports sponsorship.’

What about a link between advertising and gambling harm? Once again he hedges his bets: ‘No one has really been able to demonstrate a causal link between advertising and gambling problems. We know that advertising has a greater effect on people who already have a gambling problem.’

Where would he fall on the spectrum between ‘free for all’ on the one hand and a ban on the other?

“My role is to be impartial and not to have strong opinions in any direction,” he insists, adding that his approach is always guided by the evidence. He warms to his theme.

“The UK probably has the most liberalized gambling industry in the world,” he says, emphasizing that banned operators would drift underground with no protection for gamblers and “rampant crime”. He notes that 44 percent of the adult population – 22.5 million people – gamble at least once a month.

Gambling has long been a widespread leisure activity and the vast majority of people have no problem with it, Rhodes says. He accepts that some have ‘terrible problems’ that lead to ‘terrible consequences’ – although one of the biggest problems is predicting who will succumb.

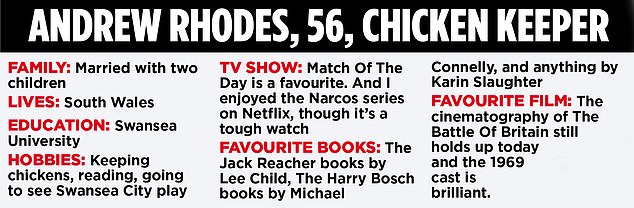

Rhodes was the first in his family to go to university – in Swansea – where he went on to work at the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency.

He subsequently became Chief Operating Officer at the Foods Standards Agency and Operations Director at the Department for Work and Pensions before heading up the Gambling Commission. Its job is to ensure that gambling is fair, open and clean. It will also collect a planned £100m levy on operators – 1 per cent of gross profits – to treat gambling addiction. It resembles the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in acting as judge, jury and executioner, granting licenses, enforcing compliance, imposing unlimited fines and revoking operators’ right to trade.

‘Over the last three years we have taken action against 46 operators amounting to £103 million in fines. We are taking serious action to ensure they follow policies and procedures,” Rhodes said. Some companies appealed, but “none succeeded,” he notes, adding, “We’ve had a lot of success shutting down illegal Facebook lotteries.”

Like the FCA, Rhodes’ remit concerns money laundering. He says: ‘Gambling has always been very sensitive. There is still a lot of money in gambling. That is why the origin of the funds is strictly monitored.’

One of the reasons he wants to see fewer betting ads on football grounds is that he and his teenage son are ‘huge’ Swansea City fans and go to a lot of home games, so ‘it’s quite a tricky issue’.

He is also chairman of the Championship club’s charitable foundation and played a key role when the Swans replaced betting company YoBet with the local university as shirt sponsor in 2020. He says: ‘I was Chief Operating Officer at Swansea University at the time, so I was on the other side of that deal!’

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on it, we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow a commercial relationship to compromise our editorial independence.