The explosive secret of the squirting cucumber: Incredible footage shows how the species can blow out slime at speeds of 70 km/h

‘Squirting cucumber’ may sound like a vulgar euphemism, but it is truly one of the most remarkable species in the natural world.

The quirky plant, a relative of the edible cucumber, ejects its seeds at a speed of up to 45 miles per hour – even faster than human ejaculate (about 45 miles per hour).

Now a new study reveals exactly how the squirting cucumber – native to southern Europe and northern Africa – accomplishes this awe-inspiring feat.

Scientists from the universities of Oxford and Manchester say the plant builds up pressure and stiffens to get the perfect angle for seed dispersal.

This increases the chances of survival because the seeds are more likely to be transported to more favorable environments for growth.

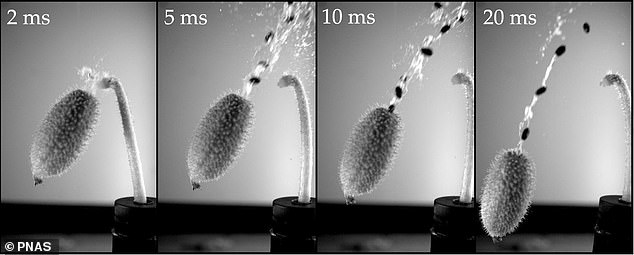

Amazing footage shows the 30-millisecond action – described as ‘one of the fastest movements in the plant kingdom’ – was slowed down 400 times.

“For centuries, people have wondered how and why this extraordinary plant sends its seeds into the world in such a violent way,” said study author Dr Chris Thorogood, head of science at the Oxford Botanic Garden.

‘Now, as a team of biologists and mathematicians, we have finally begun to unravel this great botanical enigma.’

The spray cucumber is officially called Ecballium elaterium and is named after the ‘violent’ ballistic method the species uses to disperse its seeds

A photo still showing the jet ejected by a spurting cucumber, which propels its seeds to distances of up to 10 meters away

The spray cucumber, officially called Ecballium elaterium, consists of an egg-shaped fruit attached to a long, thin stem.

When the fruit is ripe, it detaches from the stem and ejects seeds in a high-pressure jet of ‘mucilage’ – the thick, glue-like substance produced by almost all plants.

Despite intriguing scientists for centuries, the exact mechanism of seed dispersal and its effect on subsequent generations remain poorly understood,” the team said in their paper, published in PNAS.

To find out more, researchers at the Oxford Botanic Garden filmed the plant’s climactic moment (the seed dispersal) with a high-speed camera, capturing up to 8,600 frames per second.

They also measured fruit and stem volume before and after dispersal, calculated its hardness, performed CT scans and tracked the fruit with time-lapse photography in the days leading up to the big moment.

They then developed computer models to unravel the mechanics of the pressurized fruit, stem and seed trajectories.

It showed that the launch of the projectile – which lasted just 30 milliseconds – caused the seeds to reach speeds of about 44 miles per hour (20 meters per second).

This is even faster than human ejaculate: about 45 kilometers per hour!

The spray cucumber consists of an egg-shaped fruit attached to a long, thin stem (photo)

The spray cucumber is native to parts of Southern Europe and North Africa. Pictured on the left is the plant in the Oxford Botanic Garden. Shown at right is a CT scan of the cucumber, showing the seeds arranged in pairs, attached to four pillars located at 90-degree intervals around the long axis of the fruit

The seeds of the squirting cucumber then land at a distance of up to 10 meters (about 250 times the length of the egg-shaped fruit).

The researchers found that the squirting cucumber goes through several phases as part of its dramatic expansion, many of which pass faster than the blink of an eye.

In the weeks leading up to the ‘ballistic ejection’, the egg-shaped fruit comes under increasing pressure due to a build-up of mucous fluid.

In the days before dispersal, some of this fluid is redistributed from the fruit to the stem, causing the stem to grow longer, thicker and stiffer (ooh matron!)

This causes the fruit to rotate from nearly vertical to an angle of nearly 45 degrees, a key element necessary for successful seed launch.

But as the images show, it’s the separation between the fruit and the stem that can be especially eye-catching for male viewers.

In the first few hundred microseconds of ejection, the tip of the stem recoils from the fruit, causing the fruit to rotate in the opposite direction.

The seeds ejected first are the fastest and thus travel further, while the next seeds come closer – simply because the pressure of the fruit capsule decreases as it empties its load.

In the days before dispersal, moisture is redistributed from the egg-shaped fruit to the stem, causing the stem to grow longer, thicker and stiffer. This causes the fruit to rotate from nearly vertical to an angle of nearly 45°, a key element necessary for successful seed launch

In the first hundreds of microseconds of ejection, the tip of the stem withdraws from the fruit, causing the fruit to rotate in the opposite direction

Because there are multiple fruits around the center of the plant, the result is a wide distribution of seeds covering a ring-shaped area up to 10 meters away from the mother plant.

The team’s computer model also showed that if the stem was thicker and stiffer before climax, the seeds would be launched almost horizontally, because the fruit would rotate less during discharge.

Meanwhile, reducing the amount of fluid redistributed from the fruit to the stem resulted in a fruit that was overpressured, ejecting the seed at higher velocities but with a near-vertical launch angle.

In either case, the seeds would not be emitted as far and fewer seeds would likely survive, which would ultimately mean less reproductive success.

The team says the seed projection method of the syringe cucumber has evolved over generations to become as effective as possible.

“The redistribution of moisture from the fruit back to the stem and the corresponding stiffening of the stem prior to seed ejection appears to be a mechanism unique to this species,” they conclude.

‘Our comparative analysis has shown that these mechanical details are crucial for the successful dispersal of seeds and propagation of the plant to subsequent generations.’

According to Dr. Thorogood, the ancient Greeks were aware of the squirting cucumber, which is inedible due to the toxic chemicals contained in it.

The first observations are those of Theophrastus, a philosopher who, according to the academic, lived from 371 to about 287 BC.