The director of Robot Dreams founded an entire animation studio just to adapt a graphic novel he loved

In 2018, while thinking about his next film, director Pablo Berger happened to crack open one of his favorite graphic novels, a short, wordless story about a dog and a robot, best friends separated and drifting apart. Berger had read Sara Varon’s Robot dreams before, but rereading it surprised him.

“This time, when I got to the end of the book, that last act, I was so moved by the story that it actually brought me to tears,” Berger told Polygon in an interview ahead of the film’s limited theatrical release. “I was so shocked by the story. Right at that moment I thought there was something very special about the book. Then I decided to edit it and make it an animated film, even though it was something new for me.”

Varon’s book is a surprisingly poignant look at the ephemeral nature of friendships, and Berger was determined to capture that in his film. He had written and directed three celebrated, successful live-action feature films: Torremolinos 73, Abracadabraand the Spanish entry for the 2012 Academy Award, Blancanieves. But making an animated film would be different. Completely different.

“I was really scared to start production,” he says. “But I like challenges. It didn’t block me. It really got me excited, the fact that it was something new.”

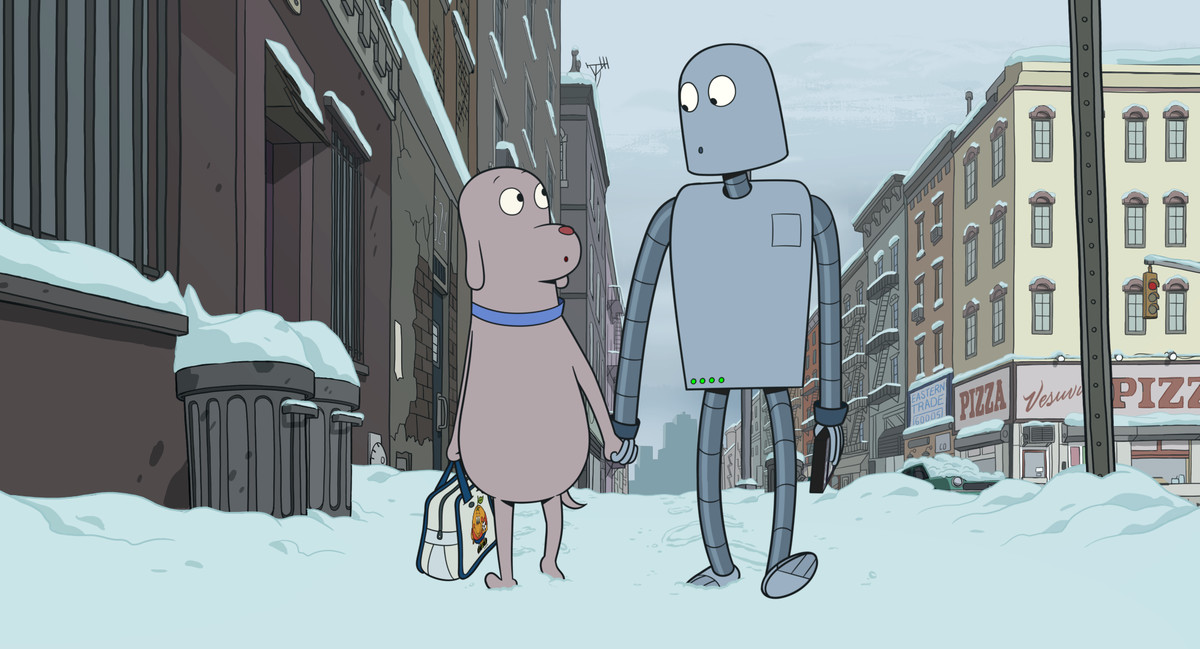

Image: Neon

But despite his lack of experience, Berger’s Robot dreams captures the surprising poignancy of the book, while using the extra space of a feature film to expand its central relationships. It is set in 1980s New York City, in a world populated by anthropomorphic animals. When one of them, Dog, feels lonely and isolated, he orders a robot companion. And after a whirlwind summer together, the band comes to an end Earth, Wind & Fire’s ‘September’ they become best friends.

But during a trip to Coney Island, Robot is knocked out and stranded on the beach, and when Dog returns to save him, he finds that the beach is closed for the rest of the year. The rest of the film follows what happens to the two during their time apart, and how they forge new connections while never forgetting each other. It’s a beautiful musing on friendship and the space we keep in our hearts for those we’ve left behind (in this case, quite physically and literally).

After a limited release, Robot dreams was also nominated for the Oscar for best animated film Spider-Man: About the Spider-Verse, NimonaAnd The boy and the heron. The film will finally debut in U.S. theaters this summer, starting with a small release in New York City on May 31. Berger is excited to see his film gain traction after its surprise Oscar appearance, especially since it’s a story he’s so passionate about. That passion drove the production, despite the challenges for a novice animation director. And there were some big challenges. Berger was originally going to collaborate with Irish animation studio Cartoon Saloon (Wolfrunners, Kells’ secret) for Robot dreams. But during the COVID-19 pandemic, production hit a snag, and Berger had to pivot.

“Suddenly we had to create our own studios in Spain,” he says. “So we called them pop-up studios, because we had to create them from scratch. We had to find the offices, buy the computers, hire animators and artists from all over Europe and create a pipeline. So that was very difficult.”

Image: Neon

Berger quickly learned some key differences between the production of a live-action film and an animated film. First, there are no individual hair and makeup department heads or cameras in an animated film; it all falls under the art department. And there are no actors in a film without dialogue; the animators do all the ‘acting’.

“At the same time, I had to achieve the same goal,” says Berger. “Three-dimensional, emotional, believable performances.”

Berger tells us that in his live-action work he talks to actors and looks deep into their eyes to bring out the most emotionally truthful performance he can. And with Robot dreamshe wanted to follow the same approach – just slightly modified, of course, since there were no actors with whom he could make that connection.

“When I looked at the animation of the drawings, I looked at the pupils of the characters,” he explains. “So basically, to bring a truthful, believable performance that can move the audience, so that the audience can have empathy for Dog and Robot.”

Image: Neon

Berger says he enjoyed every minute of working on it Robot dreams, and he would like to make another animated film in the future. There is a persistent prejudice against animation, especially in the United States, which is mainly seen as a medium for children’s films. But Berger, like Guillermo del Toro and Phil Lord and Christopher Miller before him, is adamant that animation is not a genre.

“Animation is just a way to tell the story. And animation is not just for children. There are so many great animated films that could be for kids, but also for adults,” he says, citing Persepolis, The Belleville Triplets, and the filmography of Studio Ghibli. While Robot dreams is family-friendly, Berger says his studio never compromised to appeal to children during the filmmaking process. Targeting a specific audience was actually the last thing on his mind.

“I like to make an analogy with film. Movies are like lasagna to me. And there are different layers. Every audience gets a different layer,” he says. “In a way, it looks back to when I was a kid and saw the same movie as my parents. Some of the films released in recent decades seem to be aimed at (only) cinephiles, or for commercial audiences, or for children. I think (Robot dreams) is really for a very broad audience.”

Robot dreams opens May 31 in New York City and will eventually roll out in theaters nationwide.