The dark history of America’s newest national park revealed

Set in a barren landscape miles outside of Denver, the Granada War Relocation Center is an unlikely tourist destination.

With its barbed-wire fence and dilapidated army barracks, it’s even harder to imagine it as a home.

But for 7,500 Japanese Americans, this is exactly what the concentration camp became when they were forcibly buried there during World War II.

The site was one of ten relocation centers established during a wave of anti-Japanese sentiment in the aftermath of the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor.

The attack prompted President Roosevelt to authorize the military to remove any individuals deemed a “threat” to national security – resulting in the mass expulsion of 120,000 Japanese Americans.

The Granada Relocation Center, a Japanese relocation center in Colorado, has become the US’s newest and most unlikely national park

Today, the abandoned camp has been turned into the Amache National Historic Site, the US’s newest national park, designed to preserve a particularly dark chapter in the country’s history.

At its peak, Amache was 50 percent busier than New York City.

Among those packed into the one-square-kilometer compound were the family of Dr. Kirsten Leong, whose maternal grandmother was being held in Amache.

She explained to the BBC that the trauma of the experience prevented it from being openly discussed within the family circle.

“The fact that I didn’t know much about the experience is quite common for my generation,” she explained.

Leong’s grandmother, like many Japanese Americans, was given just two weeks’ notice to pack up and leave her LA home.

Initially, they were housed 13 miles away at the Santa Anita Race Track, home of the famous thoroughbred Seabiscuit.

“My grandmother always turned up her nose and made a face,” Leong said. “I never understood that until I heard that the horses were in the stables three days earlier.”

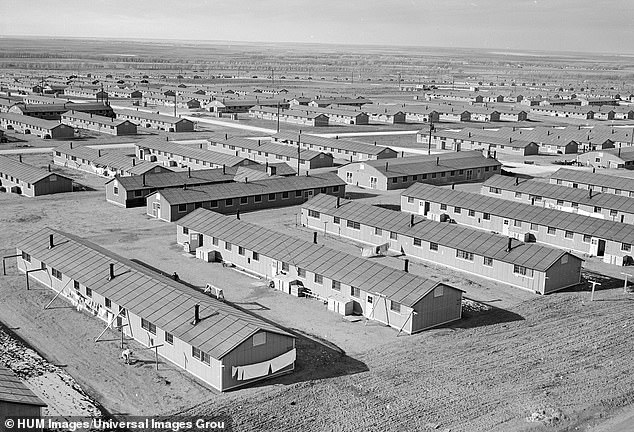

The concentration camp was once home to 7,500 Japanese Americans who were expelled from their homes under the guise of national security after the attack on Pearl Harbor

The camp was divided into 29 blocks, each with twelve barracks, which were constantly patrolled

These temporary processing centers were hastily put together, often using the labor of those imprisoned there.

After a few months, Leong’s family was moved to Amache, miles away from the community they knew.

Upon arrival they would have found the camp arranged divided over 29 blocks, each with 12 barracks.

A typical family lived in a barracks with five others, with only one bathroom to share.

The first winter at the center was particularly challenging because most of the internees were from California and did not wear heavy clothing.

A family consisting of seven or fewer members was assigned to a cramped room measuring 6 by 7 meters.

They tried that decorate the rooms in a more homely way, with shelves, partitions and rough furniture made from scrap wood.

Today, a few ghostly ruins are all that remain of the once vibrant community.

While the internment policy was intended to destroy the Japanese American community, the prisoners worked hard to build a life for themselves within the confines of the camps.

While the internment policy was intended to destroy the Japanese American community, the prisoners worked hard to build a life for themselves within the confines of the camps.

Families grew crops, schools and hospitals were built, along with a large number of shops, barbershops and sports clubs.

But behind the barbed wire fence, armed guards patrolled the area day and night.

What remains has been preserved largely thanks to the work of former Granada High School teacher and current principal John Hopper.

Hopper began documenting Amache’s history in 1993 as part of a class project before recruiting volunteers and organizations to help reconstruct some of the buildings.

Since then, a decades-long restoration project has been taking place at the location, including the renovation of the recreation hall and the cemetery.

Dr. Bonnie J Clark, professor and curator of archeology at the University of Denver, co-leads the Amache Project and conducts archaeological fieldwork at the site every two years.

The Amache Project hopes to preserve and renovate the historic site to honor the painful chapter of American history

So far she has managed to uncover sumo pits, Japanese baths, sports fields and remains of gardens.

‘That investment in a place [where] people didn’t choose to live, I think, it really speaks to an emphasis on your own humanity and also on taking care of each other,” Clark said.

Plans are now in the works for a dedicated visitors center and more educational programs.

“It’s a story that needs to be told so it doesn’t happen again,” said Christopher Mather, Amache’s site manager.

Similar horrors to those that unfolded in Amache occurred throughout the country.

Other concentration camps in the US included Tule Lake in California, Heart Mountain in Wyoming and Minidoka in Idaho.

They varied in size, but all were built on remote public land, far from civilization, in an effort to make life as challenging as possible.

Amache was the only camp built on private land that was seized by the federal government.

About 106 people died at the Granada Relocation Center, although their remains were removed when the camp closed

It was finally closed in 1945 and most of the buildings were sold and demolished.

“They were allowed to go back ‘home’, but there was no home to go back to,” Leong said. ‘My generation [is] I now discover, ‘Oh, so why don’t I know any other Japanese people. That’s why we don’t talk about our heritage.’

But for the 106 people who died in the camp, there was no return to a home.

Today, the columbarium where the ashes of the deceased were once kept has been transformed into a monument to those who died in the camp.

The Amache Project hopes this will ensure their stories continue to be told.