The curious case of Jade Jones’ missed drugs test and why the Chinese might be quick to ask questions, writes RIATH AL-SAMARRAI

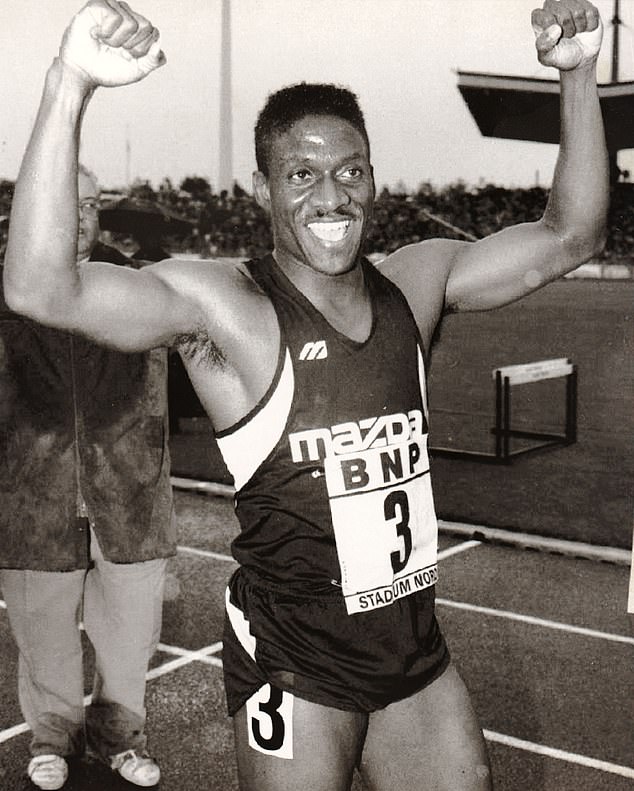

There is a well-established precedent for surprise apologies when a doping violation is laid at an athlete’s doorstep. An oldie but goodie will always be found in the life story of Dennis Mitchell, once an Olympic medal-winning sprinter for the United States who has traveled to Paris for these Games as Sha’Carri Richardson’s coach.

If we go back to 1988, he got into trouble after he was caught with high testosterone levels in his sample. His reasoning became a classic in the genre, as he would attribute it to the fact that he had sex with his wife ‘at least’ four times a night. As he himself put it: ‘It was her birthday, the lady deserved a treat.’

That play was not entirely successful: he was suspended for two years and more than thirty years later it still pops up in jokes and columns.

It’s always easier to chuckle when the shame is outside our own borders. Just as at times like this in a four-year Olympic cycle it’s a reflex to assume the worst of those outside if an excuse sounds a little off. By extension, we always seem to give a little extra room for doubt when Britons are involved in a doping case.

This was one of those months. The Chinese swimmers? You probably know them by now, and more specifically the 11 here in France who were among a group of 23 who failed tests for a banned substance ahead of the 2021 Tokyo Games.

I feel uneasy about the lesser-known case closer to home involving Jade Jones, a two-time Olympic taekwondo champion who is aiming for a hat-trick in Paris, writes Riath Al-Samarrai

If we go back to 1988, Dennis Mitchell got into trouble after he was caught with high testosterone levels in his sample

The Chinese swimmers? You’ve probably heard of them by now, particularly the 11 here in France (including Qin Haiyang, pictured) who were among a group of 23 who failed tests for a banned substance ahead of the 2021 Tokyo Games.

They were acquitted because the authorities accepted that they had been infected in the same hotel kitchen, even though there are now suggestions that they were not all staying there. The nature of that investigation and the associated allegations of an Olympic cover-up have left many of us extremely worried.

But I also feel uneasy about the lesser-known case closer to home, surrounding Jade Jones, a two-time Olympic taekwondo champion who scored a hat trick in Paris.

Her scenario, which only came to light two weeks ago, is unlike anything I have ever seen in the doping world, as she committed an offence by refusing to take a drugs test in December last year and was ultimately spared a four-year sentence because she had a “loss of cognitive capacity”. In fact, she was given no suspension at all for such a serious offence, with UK Anti-Doping ruling that she had “no fault or negligence”.

There is much interesting detail in the eight pages of their report, and it is tempting to consider how it might be perceived abroad. How we might kick it in the other foot.

The story goes back to 6:50 a.m. on December 1 at the Leonardo Hotel in Manchester, where Jones was staying. As any top athlete in this country, especially a 31-year-old woman who won her first gold at 19 at London 2012, is known to do, a tester showed up. Having spent her entire adult life on the Olympic program, she knows how to do it—it’s drilled into her through repetition. Classroom lessons, literature, prompts about how one mistake can bring down the walls. Jones refused to take the test.

She explained her reasons, which might be interesting in another discussion about athlete welfare: she told the female collections officer that she was scraping weight for a 10 a.m. weigh-in that morning and that she had not eaten or drunk anything since November 29. She would therefore not be able to provide a urine sample and was also about to go home to take a dehydration bath.

Things get murky when she refuses to allow the officer to accompany her, despite the latter’s willingness to travel and keep her under surveillance until she was ready to do what was necessary. By the time Jones left the hotel, at 7.43am, she had been reminded ‘about five times’ of the consequences of refusing to take the test and had been further advised to comply in a telephone conversation with GB Taekwondo’s performance director Gary Hall.

The legal issues spread over the next few months. There was a meeting in February with UKAD, Jones and her lawyer in which the report says she explained that she was “stressed and panicked” that December morning about her weight situation. She also confused the serious consequences of a refusal for those bound by the three-strikes rule for missed tests. Again, this was a seasoned Olympic athlete.

We should state here that there is no suggestion that Jones committed any wrongdoing, other than the offence of refusing a test. But it is a remarkable situation for such an experienced athlete

The Chinese swimmers (including Zhang Yufei, left, and Wang Shun, right, who claimed gold in Tokyo) were cleared after authorities acknowledged they had been infected by the same hotel kitchen

Seven weeks after that meeting, Jones had a new legal representation and a new thread to her legal argument. They presented a medical condition, the nature of which was omitted from the UKAD report, and it was one that, according to a consultant psychiatrist she had instructed, was ‘quite capable of causing a complete loss of cognitive capacity’ and ‘fully explains the situation in question’. A psychiatrist brought in by UKAD agreed and the evidence was ‘compelling’ in Jones’ favour.

Looking ahead to the present, Team GB are perfectly happy with Jones’ place in the delegation. As noted by their highly respected chef de mission, Mark England, Jones later that same day on December 1st failed a drugs test and was subsequently cleared.

What he got wrong was the time frame. He said, perhaps in a colloquial way, that it was ‘a couple of hours later’. It was actually 7.20pm, according to the UKAD report, so closer to 12 hours, and in theoretical discussions about doping and the passage of substances through a system, we know that numbers can matter.

It should be noted here that there is no suggestion that Jones committed any wrongdoing, other than the offence of refusing a test. But it is a remarkable situation for such an experienced athlete.

It’s the kind of fight that seems to have a compelling medical explanation. But it’s also one that we might view a little differently at home if it were one of Jones’ rivals. It’s one that those same rivals might view a little differently themselves – if the opportunity arises, it would be particularly interesting to hear the thoughts of the Chinese delegation, including their fighter, Luo Zongshi, the 2022 world champion who is in the same weight class as Jones.

They saw no problem. Or perhaps they shared the view of Renee-Anne Shirley, a former director of Jamaica’s anti-doping agency and a known whistleblower, who said two weeks ago that it “smacks of preferential treatment.”

She continued: ‘From the outside, it looks like this is your gold medalist who refused to take a test and escaped any sanction. After this, anyone can say, “I have a problem with mental illness” and not take a test.’

Whether rightly or wrongly, it is a point worth considering as we throw stones into our glass house every four years.

Friday night’s four-hour parade of interpretive dance, inspirational messages and floating staircases only reinforced the instinct that there had to be a better way

Starting with the steer to the bottom of the Seine and continuing with the hop, skip and jump

Personally, I hope most of all that Katarina Johnson-Thompson finally gets her medal

Must be a better way than Friday’s four hour parade

A thought on the Olympic Opening Ceremony. It’s only right that there should be some kind of price to pay for access to what I consider the greatest sporting spectacle on earth, but Friday night’s four-hour parade of interpretive dance, ambitious messages and floating staircases only reinforced the instinct that there had to be a better way. Starting with sending the cat to the bottom of the Seine and continuing with the triple jump.

My biggest hope for these Olympic Games

It is rumoured that most of the British medals will come from cycling and rowing, with a pleasant surprise from athletics. The boxing programme, it is feared, will not be at its usual weight. Personally, I am most hoping that Katarina Johnson-Thompson finally gets her medal. No one embodies the Olympic spirit of perseverance better.