The Crystal Palace mystery is SOLVED: Scientists finally discover how the vast structure – then the largest building in the world – was built by the Victorians in just 190 days

It was one of the largest structures in Britain, built in just 190 days between 1850 and 1851 – just in time for Prince Albert’s Great Exhibition.

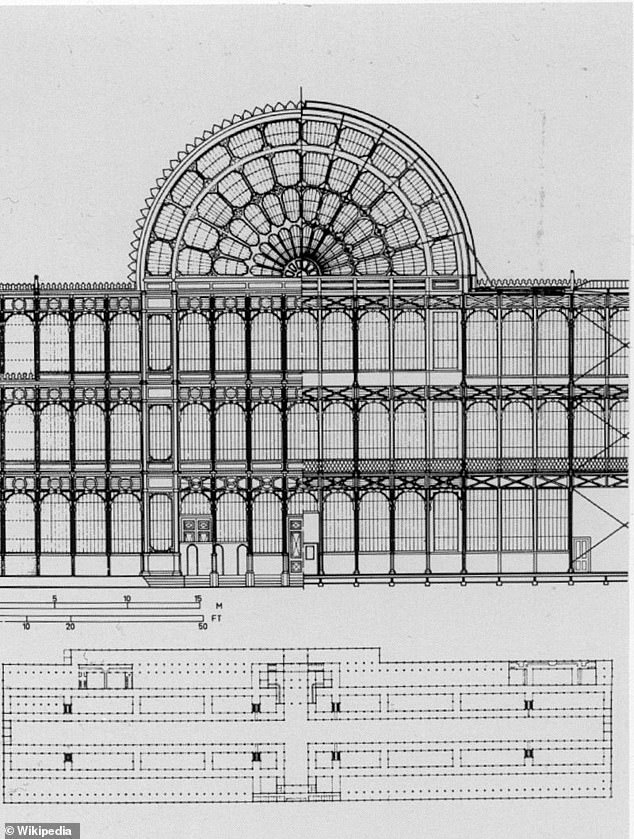

Now an investigation is solving the mystery of how the 560-metre-long Crystal Palace in London, at the time the largest building in the world, was assembled so quickly.

According to researchers, the massive glass building pioneered the use of identical nuts and bolts, mass-produced by machines to achieve one standardized size and shape.

In the past, nuts and bolts were laboriously made by hand – and no two screws and bolts were the same.

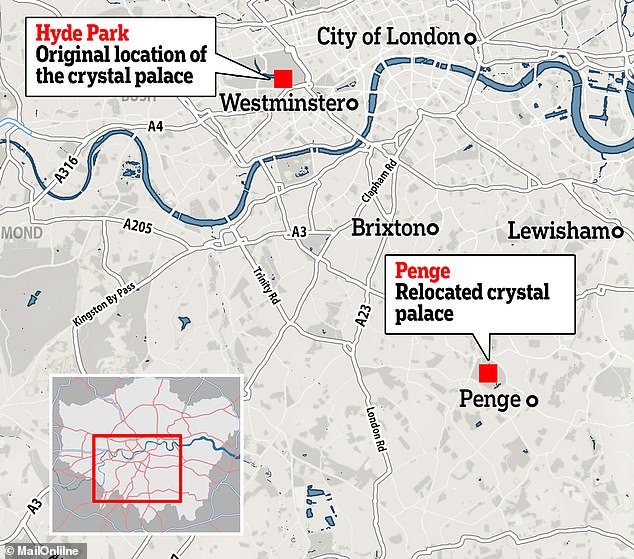

The Crystal Palace was designed by the famous English architect Sir Joseph Paxton and built in Hyde Park. It cost £80,000 to build (almost £10 million today).

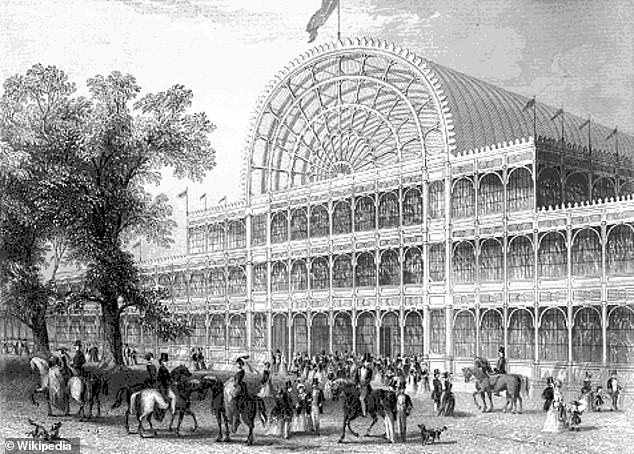

The original Crystal Palace was a huge exhibition building built in London’s Hyde Park between 1850 and 1851 (shown in this drawing)

After the Exhibition, the palace was moved to Penge Common, near Sydenham Hill in south London, where it remained until it was destroyed by fire in November 1936.

The 1851 World’s Fair was held here, a major event featuring sculptures, machines, diamonds, telescopes and much more from around the world.

After the Exhibition, the palace was moved to Penge Common, near Sydenham Hill in south London, where it remained until it was destroyed by fire in November 1936.

The new research, led by Professor John Gardner at Anglia Ruskin University (ARU) in Cambridge, shows that these standardised nuts and bolts were first used in the palace. They were devised by Victorian inventor Joseph Whitworth.

“During the Victorian era, incredible innovations took place across Britain that helped change the world,” said Professor Gardner, who published his study in 2006. The international journal for the history of technology and engineering.

‘In fact, progress was so rapid that some breakthroughs may never have actually occurred, as in this case at the Crystal Palace.’

Completed just in time for the opening of the 1851 Great Exhibition, the Crystal Palace was a powerful symbol of Britain’s industrial might in the Victorian era.

At 564 metres long and with a gigantic glass roof supported by 3,300 cast iron columns connected by 30,000 nuts and bolts, it was the largest building in the world at the time.

Because the successful design for the Crystal Palace was not approved until July 1850, historians have long puzzled over the speed at which construction proceeded.

Professor Gardner worked with Ken Kiss, curator at the Crystal Palace Museum, who had excavated the original columns from the Crystal Palace site at Sydenham.

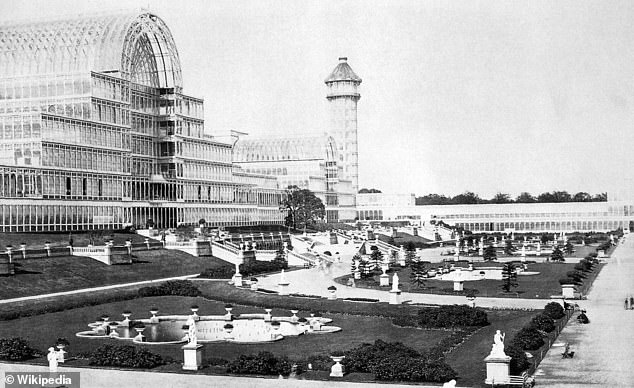

The building was demolished and rebuilt (1852–54) on Sydenham Hill (now in the Borough of Bromley), where it remained until 1936.

It was one of the largest buildings ever built in Britain, constructed in just 190 days between 1850 and 1851 – just in time for Prince Albert’s Great Exhibition

A stunning sight: The Crystal Palace hosted the Great Exhibition of 1851 – an event featuring sculptures, machines, diamonds, telescopes and much more from around the world. Pictured is the interior of the Crystal Palace during the event

The standardized nuts and bolts, which were invented by Victorian inventor Joseph Whitworth (shown here in a painting by an unknown artist)

When the academic analysed the original nuts and bolts, he found that they had all been built to a standard devised by Whitworth in 1841.

Before Whitworth’s invention, no two screws or bolts were the same. This meant that a nut made in one shop would not fit together with a bolt made in another.

And because they were not made to a standard size, lost or broken screws and bolts were difficult to replace, making construction time-consuming.

In a bolt, the thread is the long notch that loops down and around. It is precisely matched to the corresponding nut, just like a key and a lock.

It was only when Whitworth’s threads – now taken for granted in modern construction and engineering – were mass-produced that the structure could be assembled in record time.

Although the Whitworth screw thread – later known as the British Standard Whitworth (BSW) – was devised ten years before the palace was built, it was not adopted as the British standard until 1905.

Professor Gardner made new bolts to the British Whitworth standard and showed that these fitted the original nuts.

“Standardisation in engineering is essential and commonplace in the 21st century, but its role in the construction of the Crystal Palace was a significant development,” he said.

On a bolt, the thread is the long notch that loops down and around – and which fits a matching nut. Professor Gardner said he made new bolts to the British Whitworth standard and showed that they fitted the original nuts

The original Crystal Palace was a huge exhibition building built in London’s Hyde Park between 1850 and 1851 (shown in this drawing)

Crystal Palace after the move to Sydenham Hill in 1854. This area of London was later called Crystal Palace, which among other things gave it the name of the football club (founded in 1905).

Ultimately, without Whitworth and his screw threads, the 1851 World’s Fair could have been postponed or even cancelled altogether due to lack of space.

The historic event was organised to showcase the best in engineering feats from around the world and was described as a showcase for ‘every conceivable invention’.

It was visited by around six million people – a third of the British population – including famous Victorian figures such as Charlotte Bronte, Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Charles Darwin and Michael Faraday.

After the exhibition, the palace was dismantled, moved to Penge Common, near Sydenham Hill in south London, and meticulously rebuilt.

After the move, this area of South London was called Crystal Palace, which, among other things, took its name from the football club (founded in 1905).

Sadly, the spectacular glass palace was destroyed by fire in November 1936. The fire was so intense that the glow of the flames could be seen in eight provinces.

A total of 89 fire engines and 400 firefighters were deployed to battle the fire, but they were unable to control the fire.

About 100,000 people came to Sydenham Hill to watch the fire, including Winston Churchill, who said: ‘This is the end of an era.’

In 2013, a Chinese businessman unveiled ambitious plans to rebuild the palace on the south London site, but these plans were later rejected.