The body types that raise the risk of colon cancer – which is rising rapidly in young people, according to new study

Your body shape may put you at extra risk of one of the fastest growing forms of cancer in young people, a study warns.

Colon cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the US, with approximately 150,000 new cases expected in 2024 and 50,000 deaths.

Rates among people under 50 have soared in recent years, with doctors warning that alcohol, junk food and a sedentary lifestyle increase the risk.

Now a study has found that people’s body types and where they store fat (as opposed to how much they have) also play a role.

Researchers from six countries, including the US and Britain, found that people who were ‘generally obese’, as well as those who were taller and had more belly fat, were at the greatest risk of colorectal cancer

The team suggested that having more fat around the abdomen could disrupt processes such as metabolism and blood sugar levels, increasing the risk of cancer

Being ‘generally obese’ – which is usually defined as a BMI over 30 – was linked to a 10 percent higher risk of bowel cancer than people of a healthy weight.

But the researchers found that tall body types who were not defined as obese, but had a beer belly shape, were 12 percent more likely to develop colon cancer than the average person.

And women were at greater risk than men of the same build, with an 18 percent greater risk.

Junk food, alcohol and a sedentary lifestyle all contribute to a beer belly or a more apple-shaped body. It is unclear whether this body type specifically is becoming more common, although obesity is increasing in the US.

CDC data suggests that 40 percent of Americans are obese, and about 69 percent are overweight or obese. According to Harvard University, obesity rates in the US have doubled since 1980, which could explain the rise in colorectal cancer among young people.

Meanwhile, those who were tall and had fat more evenly distributed, such as on their arms, legs and breasts, or those who were short and stocky, had the lowest risk.

Overall, the former had a three percent increased risk, while the latter was five percent.

The researchers said the findings show that people with body types that store fat in one concentrated area around the intestines were at greatest risk.

They added that where fat accumulates in the body could be a better indicator of cancer risk than BMI alone.

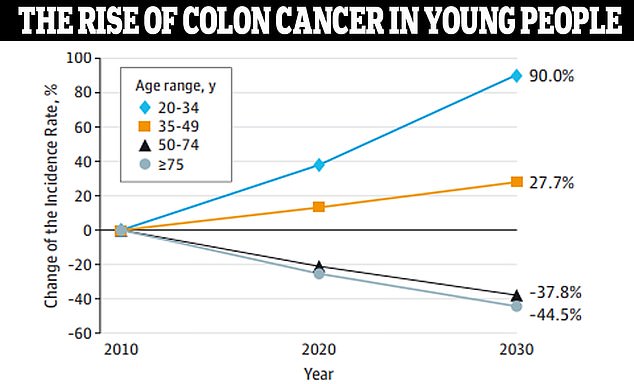

Data from JAMA Surgery shows that colon cancer is expected to increase by 90 percent in people ages 20 to 34 by 2030. Doctors aren’t sure what’s driving the mysterious increase

Jelena Tompkins (left) was just 34 when she was diagnosed with stage three colon cancer. Her first symptom was foul gas. Jill MacDonald (right) was 36 when doctors mistook her stage four colon cancer for hemorrhoids

Dr. Heinz Freisling, author of the study and scientists at the International Agency on Research in France, said: ‘We believe that the most commonly used indicators of body fat, such as body mass index or body fat distribution (for example waist circumference) can cause cancer underestimate. risk.’

‘Despite their usefulness, these indicators group individuals with a similar body mass index, but different body shapes, into the same category, when we know that people with the same body mass index can have very different cancer risks.’

The team noted that this increased risk could be due to increased levels of growth hormone, as well as fat accumulating around areas such as the breasts, reproductive organs, nerves and blood vessels.

Increased body fat, also called adipose tissue, has been shown to cause problems regulating metabolism, inflammation and blood sugar levels, leading to higher levels of the hormones adipokines.

Adipokines, including leptin, could be “potentially directly relevant to cancer development,” Dr. Freisling said.

Fat can be visceral (between your internal organs) or subcutaneous (just under the skin). Visceral fat, which is located deep in the abdominal cavity and surrounds major organs such as the stomach and liver, is also linked to a host of problems, including high blood pressure, heart disease and diabetes.

Other research has also theorized that taller people have an increased risk of cancer because they have a larger colon and more room for cancer cells to form.

The research was published in the journal last week Scientific progress.

The research team from six countries, including the US and Britain, analyzed the health records of almost 330,000 adults in the UK Biobank database to look at the relationship between height and fat distribution and bowel cancer.

The team divided the participants into four groups based on their body shape, which was determined by their height and fat distribution.

These groups were PC1 (generally obese), PC2 (tall, but with more distributed fat mass), PC3 (centrally obese) and PC4 (shorter, heavier but with lower hip and waist dimensions).

Women in the PC1 group had a risk of nine percent and men had a risk of 11 percent. Men in PC3 had a five percent risk, and women in that group had an increased risk of 18 percent.

Men in PC2 had an increased risk of one percent, and women had an increased risk of three percent. While men in PC4 had a 25 percent greater risk, women were 10 percent less likely to develop the disease.

“We believe that the most commonly used indicators of body fat, such as body mass index or body fat distribution (for example, waist circumference), underestimate the risk of cancer due to unhealthy weight,” said Dr. Freisling.

He noted that the findings show that “people with the same body mass index can have very different cancer risks.”

Furthermore, white, black, Asian and Chinese individuals with these body types were generally at the same risk, indicating that race and ethnicity did not play a role.

‘There are probably only limited possibilities, common among ancestral groups, about how body measurements such as weight and height can be combined to form a body shape,’ Dr Freisling said.

‘It also suggests that biological processes that determine body shape are evolutionarily conserved because they are molecular pathways that are critical to the individual’s survival.’

The team then plans to conduct additional research into the possible mechanisms for the impact of body shape on colorectal cancer risk.