The Band-Aid of the Future: Smart Bandage Heals Injuries 30% Faster Than Standard Bandages by Creating an Electric Field Around the Wound

- The dressing uses an electric field to promote healing of chronic wounds

- Best of all, researchers say the bandage is cheap to produce

A new study shows that a hydro-powered electric bandage can heal serious wounds significantly faster than conventional treatments.

The futuristic bandage uses an electric field to promote the healing of chronic wounds and other injuries.

Animal studies found that wounds treated with electrical bandages healed 30 percent faster than wounds treated with conventional bandages.

Best of all, researchers at North Carolina State University say the bandage is cheap to produce.

“These dressings can be produced at a relatively low cost. The overhead costs are a few dollars per dressing,” said Dr. Amay Bandokhar, co-author of the study.

A hydro-powered electric bandage can heal serious wounds significantly faster than conventional treatments, according to a new study

Chronic wounds are defined as open wounds that heal slowly, if they ever heal at all.

For example, the wounds that develop in some diabetes patients are chronic wounds.

According to doctors, such wounds are “particularly problematic” because they often return after treatment and significantly increase the risk of amputation and even death.

One of the biggest challenges with chronic wounds is that existing treatment options are extremely expensive, which can create additional problems for patients.

Dr Bandodkar said: ‘Our aim was to develop a much cheaper technology that accelerates healing in patients with chronic wounds.

The bandage is placed on a patient so that the electrodes come into contact with the wound. A drop of water is then placed on the battery, activating it. Once activated, the bandage produces an electric field for several hours

“We also wanted to make sure the technology was easy to use at home, and not something that patients could only get in clinical settings.”

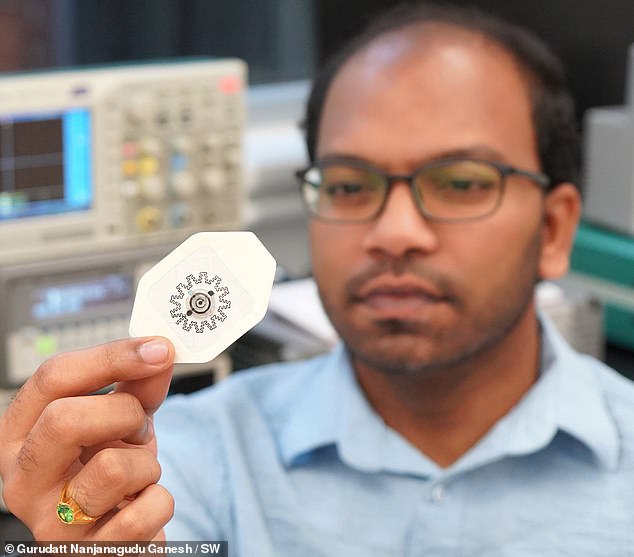

The dressing is a “water-powered, electronics-free dressing” (WPED) – a disposable dressing with electrodes on one side and a small, biocompatible battery on the other.

The bandage is applied to the patient so that the electrodes come into contact with the wound.

A drop of water is then placed on the battery, activating it. Once activated, the bandage produces an electric field for several hours.

Co-author Dr Rajaram Kaveti, also of North Carolina State University, said: ‘That electric field is critical because it is well known that electric fields accelerate the healing of chronic wounds.’

The electrodes are designed to flex with the dressing and conform to the surface of chronic wounds, which are often deep and irregularly shaped.

Dr Kaveti said: ‘This adaptability is crucial because we want the electrical field to be directed from the periphery of the wound to the centre of the wound.

The researchers now hope to test the connections in humans to see if they are just as effective

‘To effectively focus the electrical field, the electrodes must be in contact with the patient at both the edge and the center of the wound.

“And because these wounds can be asymmetrical and deep, you need electrodes that can adapt to a wide variety of surface features.”

To test the connections, the researchers used diabetic mice.

“We found that the electrical stimulation from the device accelerated wound healing, promoted new blood vessel formation and reduced inflammation, all of which suggests that wound healing is improved overall,” said co-first author Maggie Jakus, a doctoral student at Columbia University.

The researchers now hope to test the connections in humans to see if they are as effective.

Dr Bandodkar added: ‘The next steps for us are additional work to refine our capabilities to reduce electric field fluctuations and extend the duration of the field.

“We are also continuing with additional testing, which will bring us closer to clinical trials and ultimately to practical applications that can help people.”