The 16th-century Italian ‘vampire’ buried with a stone in her JAWS to prevent her from feeding on plague victims

A 16th century Italian ‘vampire’ who was buried with a stone in her mouth for fear she would feed on underground corpses has had her face reconstructed by scientists.

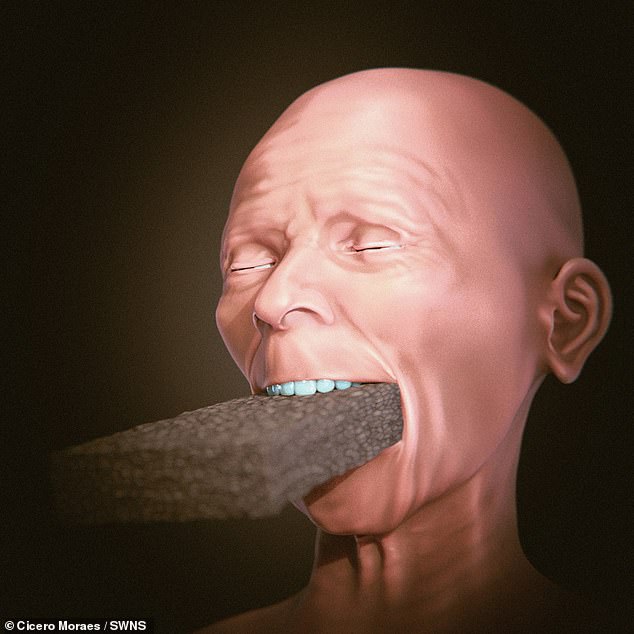

Incredible new images – created using 3D scans of her ancient skull – reveal a woman with a pointed chin, silver hair, wrinkled skin and a slightly crooked nose.

They also show what she would have looked like with the stone block in her jaws.

Experts believe the stone was placed there shortly after she died by locals who feared she would feed on fellow victims of a plague that swept an Italian town minutes from Venice.

Skeletal evidence already suggests she was 60 years old at the time of death, but not much more is known about her.

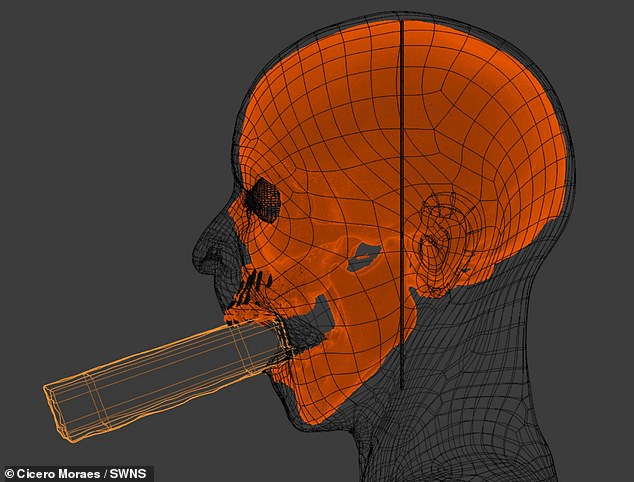

By recreating the woman’s face using 3D software, it was possible to investigate whether a stone could have been placed in her mouth

His research also allowed him to test the theory of whether inserting the stone would even have been possible without damaging the mouth and teeth

The astonishing reconstructions were created by Brazilian forensic expert and 3D illustrator Cícero Moraes, who detailed the project in a new study.

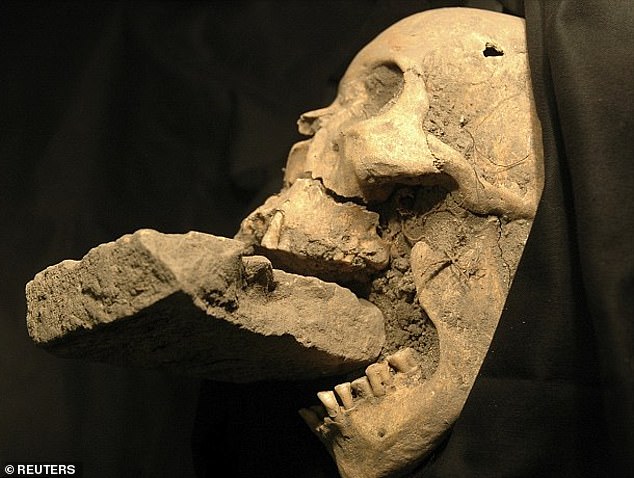

As Moraes explains, the skeleton was found in 2006 during excavations of Nuovo Lazzaretto burial pits in Venice, where plague victims who died between the 15th and 17th centuries were buried.

During the work, the skull of one of the graves attracted attention, because the jaw was open and in the oral cavity there was a stone brick.

“Studies have been conducted to find out whether the placement of the stone was accidental or intentional,” Moraes says in his paper.

‘The results rejected the first hypothesis, indicating that the placement of the stone was intentional and part of a symbolic burial ritual.’

The fear of vampires was widespread in Europe during the Middle Ages, largely due to a lack of understanding of why dead bodies would swell.

Belief in vampires led to rituals such as piercing corpses through the heart before burial.

In some cultures, the dead were buried face down to prevent them from finding their way out of their graves, but objects in the mouth were a different practice.

According to Moraes, the suggestion that the woman was considered a vampire dates back to a Study from 2010 published by forensic anthropologist Matteo Borrini.

“The anti-vampirism rituals we know today are the result of a historical evolution of the myth,” Moraes told MailOnline.

The remains of a female ‘vampire’ from 16th-century Venice, buried with a stone in her mouth, supposedly to prevent her from feeding on plague victims

The exploration of the mass grave after the outbreak of the plague in 1576 yielded one of the most bizarre archaeological finds. Images now show what she probably looked like

In 2006, the woman’s skeleton was found in a mass grave of plaque victims on the Venetian island of Lazzaretto Nuovo.

‘The study specifically addresses the belief that placing the stone made it impossible for vampires to feed and neutralize.’

Using 3D scans of the skull, Moraes estimated the distribution of soft tissue to shape the woman’s face.

The nose was then designed based on data taken from measurements of tomographic scans of living individuals of different ancestors.

“Using all the projected information it was possible to draw the profile of the face,” he says.

His research also allowed him to test the theory of whether inserting the stone would even have been possible without damaging the mouth and teeth.

Moraes recreated the stone with Styrofoam, cut to exact dimensions, to see if it would fit in his own mouth.

‘The original study includes some measurements of the stone, other images include a reference to its thickness,’ Moraes told MailOnline.

‘I cross-referenced data to generate a compatible sized brick and cut it from a piece of Styrofoam, which I painted to keep it sturdy.

‘Then I tested the placement in my own mouth, under someone else’s supervision, because I didn’t know if it would work or not.

‘It worked, so I transferred the data to the 3D model and it was compatible there too.’

3D scan of the skull of the ‘vampire’ woman in red with reconstructed tissue and the stone protruding from her mouth

Researcher Cicero Moraes recreated the stone using Styrofoam to see if it would fit in his mouth

Researcher Cicero Moraes recreated the stone using Styrofoam to see if it would fit in his mouth

Moraes says there is no surviving documentation from the woman’s life to indicate she was considered a vampire.

Instead, this arose from modern interpretations of exactly why the stone was there.

It is already known that Lazzaretto Nuovo served as a quarantine station for plague victims between 1400 and 1700.

This coincided with the fear of vampires, which was caused when locals noticed dead bodies swelling as if they were feasting on flesh.

However, Venice’s ‘vampire’ skeleton isn’t the only one found with objects in its mouth.

In 2014, researchers reported the discovery of the remains of a man in Poland with a stone in his mouth and a stake in his leg.

Remains from the eighth century in Ireland also had large stones in their mouths, which were placed there ‘by force’.