Tech powerhouse Smiths Group helps conquer space

The speed with which passengers pass through security at Dulles Airport in Washington DC would leave passengers at Heathrow with envy and awe.

They have the most advanced scanning machines in the world – capable of detecting any unwanted object – and you don’t have to take off your shoes and belt.

As a Brit always on the lookout for the country’s tech success stories, it’s hard not to feel a sense of pride in the brand on the scanner.

Smiths Group may not be Britain’s best-known company, but in the secretive world of airport security it is an international name to be reckoned with. The new scanners will be at major UK airports next summer.

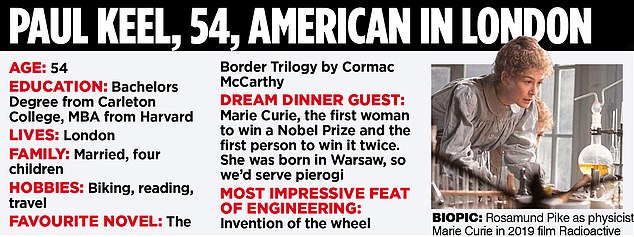

Shooting to the moon: Paul Keel, who joined in 2021, heads Smiths Group

The tradition of advanced technology at Smiths goes back more than a century. That history is on display at the headquarters of the FTSE 100 engineering giant in a pretty square in London’s St James’s.

In a glass case lies the Smiths De Luxe watch worn by Sir Edmund Hillary on his 1953 ascent of Mount Everest. It has been decades since Smiths, founded 172 years ago, last made watches, but it has its British roots and his spirit of innovation.

“We made the instrument panel for the world’s first transatlantic flight in 1919 and the speedometer for the first true British car,” said CEO Paul Keel. “This is a really cool company.”

More recently, it supported India’s successful landing at the moon’s south pole by providing parts to be used aboard the spacecraft. It also produced the communications module for the Mars rover.

Despite its role in such exciting breakthroughs, the company doesn’t always capture the imagination of investors. Keel, who joined in 2021, was called upon to change that.

Smiths shares are up about 20 percent since his acquisition, but he says they still trade at “about half the value” of industry peers like Spirex, Weir Group, Halma and Rotork.

Under Keel’s predecessor, Andy Reynolds Smith, the company fell out of favor in the stock market. That was partly because conglomerates went out of fashion and partly because frustration arose over the long-winded attempts to sell their medical device business.

Keel pushed through the sale of Smiths Medical, which was finally completed in January last year.

Now that the group has slimmed down over the course of a number of years, the group consists of four divisions. The two largest are US-based John Crane, which makes industrial seals, and Smiths Detection, which makes airport security scanners.

Flex-Tek, also based in the US, specializes in the movement of liquids and gases, while Smiths Interconnect provides products for advanced communications in satellites and aircraft.

A few days ago, Smiths bought Heating and Cooling Products (HCP) – a US-based manufacturer of heating, ventilating and air-conditioning equipment – in a £65 million deal. HCP will be integrated into its Flex-Tek division.

“Smiths has now posted eight consecutive quarters of growth and the addition of HCP allows us to continue to build on this momentum,” said Keel.

The current business is very different from the one that began as Samuel Smith’s jewelery shop on the Newington Causeway in South London’s Elephant and Castle. Smiths Group now employs 14,000 people and is valued at nearly £6 billion.

In view of the long history, Keel likes to portray himself as a long-term person. “We think in quarter-century terms, not fiscal quarters,” he says.

“Our technology is used in three-quarters of all orbiting satellites launched in the US and Europe. That’s something you’ll earn in a hundred years’ time.’

The sale of Smiths Medical does not necessarily herald a further break. Conglomerates with a predatory takeover drive used to be the apex predators of the corporate world. Now ‘focus’ – concentration on one core activity – is in vogue.

For Keel, however, what matters most is not the structure of a company, but how well it is run.

He values techniques such as ‘Six Sigma’, a set of management methods aimed at improving business processes that were all the rage in the 1990s.

Hoshin Kanri – having systems in place that try to ensure that a company’s strategy is actually put into practice – is another slogan.

It may sound like he swallowed a textbook. But in a country like Britain, where there is a huge shortage of managerial skills, focusing on how to run a business better should not be scorned.

“That’s why the stock has risen in the past two years. It has outpaced the FTSE 100 and the global industrial sector,” he says.

With his broad smile and sweet accent, Keel looks and sounds quintessentially American.

He grew up in a small town called Prior Lake in rural Minnesota as one of six children.

He met his wife Suzanne, a pathologist, in high school, and began his career at General Mills food company, where he was in charge of angel food cake and Boston cream pies.

After a stint with McKinsey consultants and in private equity, he went to US giant GE and then to 3M, the company behind Post-it Notes. There he met Yorkshire businessman Sir George Buckley, who became chairman of Smiths in 2013. Buckley will step down later this year and will be replaced by Alcoa boss Steve Williams.

There is a craze among some leaders of London-listed companies to scare off the City and move the main listing to Wall Street in hopes of a higher valuation.

As an American, with two of Smiths’ four divisions in the US, did Keel consider such a move?

“The simple answer is no, not in a serious discussion. After more than 170 years in London and 100 years listed on a London stock exchange, we would need a very good reason to deviate from that.’

He says the route to growth for Smiths is to be “a link in an important chain” on technical issues that matter to the world.

An example of this, he says, is that its equipment is used at more than 90 percent of the world’s 100 largest airports.

Manufacturing mechanical seals for high speed rotating equipment used in refineries and chemical processes is another area where Smiths excels.

Like his colleagues, Keel sees opportunities in the transition to greener energy.

Smiths makes seals for a massive hydrogen project in Alberta, Canada, and for the world’s largest carbon-free hydrogen plant in Saudi Arabia.

The company is also working with H2 Green Steel on a major project in Sweden to convert iron ore into steel using hydrogen instead of burning natural gas, reducing CO2 emissions by 95 percent.

“Capable companies like Smiths can do pretty much anything if we put in the effort,” he says. “But we can’t do everything, especially not all at once.”

The company has revised its growth outlook upwards despite the gloom over the global economy and posted record half-year results earlier this year. Part of that is due to inflation. Profit margins have increased as the company has been able to pass on price increases to its customers. Some are dealing with catching up after years of sluggish performance.

The big question is whether the growth is sustainable.

“About a third of that is just luck,” he says. “I would say another third of that is inflation related and the remaining third is due to Smiths excellence.”

Shortly after his arrival, he says, his growth ambitions were greeted with “snigger and giggles” by investors and analysts. Now, says Keel, there is laughter “for the opposite reason,” because people expect Smiths to achieve much more. It may take some time to win over the skeptics, but he hopes he has the last laugh.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on it, we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow a commercial relationship to compromise our editorial independence.