Talk about a mega find! Scientists discover world’s first fully preserved megalodon tooth from creature that lived a 3.5 million years ago

Megalodon teeth have been found on many beaches, but scientists have discovered the first on the deep sea floor that has been preserved for 3.5 million years.

Paleontologists from the University of Wyoming discovered that the four-inch tooth was located on a seamount more than 10,000 feet beneath the North Pacific Ocean near Hawaii.

The tooth is the first to be found deep in the sea, as most megalodon teeth are dredged from sediment on the seabed.

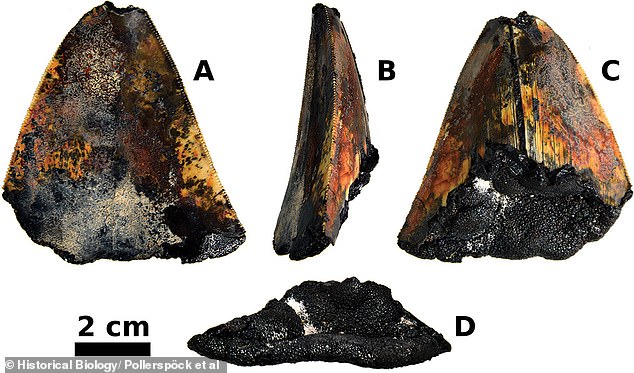

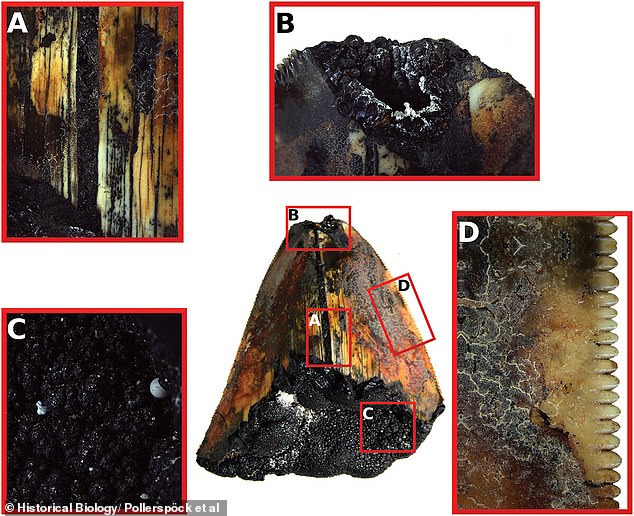

Because the specimen was only partially fossilized, the team was able to see beautiful details like never before: the enamel and spongy pulp inside were still intact.

Scientists were using a remote-controlled vehicle to explore the seabed when they spotted the megalodon tooth on their video feed

The discovery was made accidentally when scientists explored the area using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to understand its deep-sea geology and biology.

The ROV encountered the seamount and the tooth lay among the rocks, exposed and undisturbed.

Tyler Greenfield, a paleontologist at the University of Wyoming, says: 'There are areas on the seafloor, especially deep ocean basins far from the mainland, where little to no sediment deposition occurs for long periods of time.

'It is also possible that teeth are eroded and reworked into younger sediments, but that probably did not happen in this case.'

The ugly jagged cut edges were still intact, indicating it did not break away from the surrounding rocks and tumble around in the ocean before it was found.

Many fossilized shark teeth found on beaches worldwide are smoothed out by this process after being loosened from the rock formation in which they were trapped.

But in the case of this new copy, the frayed edges tell a different story.

Part of the reason for this, the researchers wrote, was location.

The tooth appeared to be broken but well preserved. It still had the jagged edges and even some enamel

Fossils usually form when a dead plant or animal is covered by soil or sand, such as marine animals such as the megalodon.

As more and more layers of sediment accumulate over the body, minerals replace bones or cell walls, turning the remains into a perfect rock copy of the original.

This is why most fossils are found wedged into the layers of sedimentary rock formations.

But nothing like that happened with the megalodon tooth.

It has spent the last few million years on an undersea ridge, where ocean currents prevented sand from covering it.

Something else made the specimen unique: only the outside of the tooth appeared fossilized.

The tip had broken off, as had the base, exposing the spongy pulp inside.

The mineral manganese began to crust the tooth, but so far this had only partially happened.

Detailed images of the tooth show (A) the enamel; (B) the broken point with a cavity in it; (C) the mineral manganese crust on the exposed pulp; and (D) the intact serrated edge

When manganese fossilizes a tooth with the inside exposed, the result is usually just the enameloid: a hollow tooth shell.

Deep sea worms are known to feed on the exposed pulp of shark teeth, speeding up the process.

It was impossible to say whether that happened, “although the remarkably large teeth of megatooth sharks would certainly provide a great food source,” the study authors wrote.

The fossil description was published in the journal Historical biology.

According to previous research on such fossils, most megalodons appeared to live on the coasts.

The remains of this prehistoric shark are usually found in coastal rock formations.

And although this tooth was found far from dry land, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, it is not the first to be found on the seabed of the open ocean.

Records show that other megalodon remains have been found there.

“A possible explanation for the distribution of the sites could be transoceanic migration,” the authors wrote.

The great white shark, which replaced the megalodon as the ocean's largest shark, is known to migrate.

They concluded that this rare find shows how important it is to continue exploring the deep sea with high-tech equipment.