I nearly died in an avalanche – the eerie visions of each heart-stopping second still haunt me and almost drove me to suicide

‘This morning I will be buried alive. I will slowly run out of air and suffocate under the snow.

‘They will find my body in the spring, when my orange down suit emerges from the melting snow and feathers float from the tears.’

These were the thoughts running through the mind of adventurer and National Geographic photographer Cory Richards when he was hit by a devastating avalanche on the world’s 13th highest mountain.

In his new book, The color of everythingRichards describes in breathtaking detail how his life flashed before his eyes – sometimes bizarre, sometimes almost mundane.

Richards was the first (and still the only) American to climb any of the world’s 8,000-meter mountains in winter. In February 2011, he reached the summit of Gasherbrum II in Pakistan.

He and his fellow climbers – Denis Urubko and Simone Moro – were descending that record-breaking climb when they were swept away by a sudden avalanche.

“A chunk of ice falls down, too many crystals land on the ground, or the wind blows in the wrong direction and I hear it before I see it,” he writes, recalling the moment the avalanche struck.

Richards filmed himself collapsing shortly after the avalanche for the short documentary ‘Cold’

He writes: ‘They will find my body in the spring, when my orange down suit emerges from the melting snow and feathers float from the tears’

‘It sounds like thunder, a freight train and wind all at once.

‘I try to run, but the snow is up to my waist and too heavy. I take three steps before the air blast lifts my body and I am weightless.

‘I’m slamming back into the tongue of the avalanche… tumbling over and over in an exploding pile of down and nylon… and it’s only two colors. Black and white. Black and white. Over and over and over.’

As the snow filled his open mouth and nostrils, making it difficult for him to breathe, he was unable to scream.

‘Colorful splinters appear amidst violent flashes of black and white as the weight of my body is sucked deeper into the rubble. Down is up. Up is down,’ he writes

Meanwhile, his emotions changed from fear to instinct, to anger, and finally to resignation.

Richards – who has been open about his mental health struggles – reveals that, convinced these were the last moments of his life, memories appeared in disjointed fragments: “A birthday. A date. A bowl of Cheerios. Parking tickets. Song lyrics and books and movies. Faces and things unsaid and words I wish I could undo and actions I want to undo and things I never did, and I remember paying taxes.

‘Life flashes before my eyes, but there is no poetry in it. They are just polaroids of a collection of things, emotions and questions.’

This is what it feels like, he writes, to die in an avalanche: a clash of feelings, thoughts and helplessness.

Summoning all his remaining strength, he threw his head and hand toward what he hoped was “up” and, miraculously, found air. Completely buried except for one arm, his chin held above the snow, he took his first hysterical gasps for air and began desperately trying to free himself before the next avalanche came.

As he struggled in the snow, crying and convinced his friends were dead, he suddenly heard Simone’s voice: “Cory, I’m okay.” And then Denis: “Simone! I’m okay too!”

All three of them were still alive, despite all the setbacks.

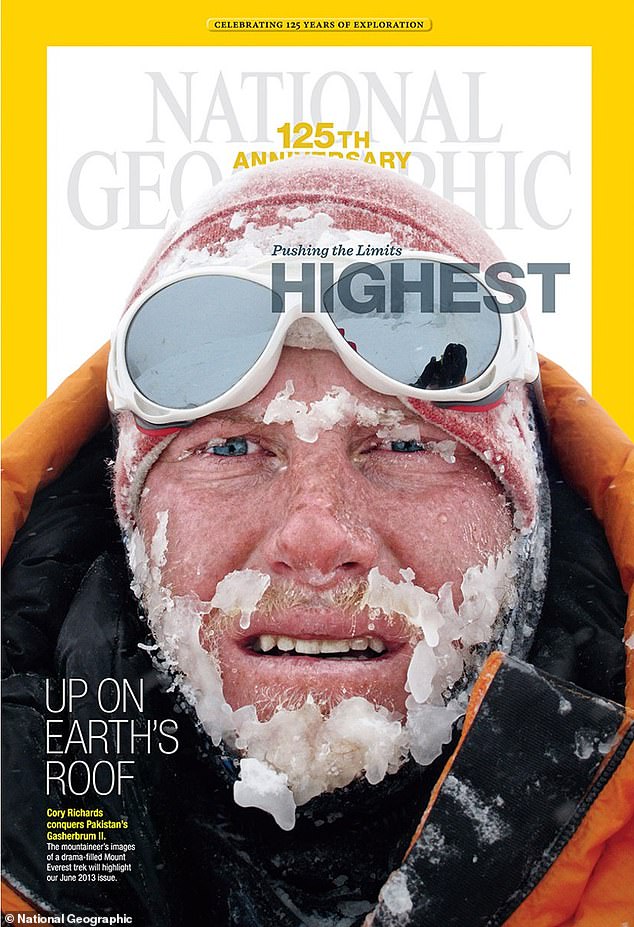

The climb made Richards famous. In addition to his ice-covered face gracing the cover of National Geographic’s landmark 125th issue, he made the award-winning documentary “Cold.”

“Talking about pain, anger, frustration, and all the rest of it is not weak and does not make anyone a ‘snowflake,’” Richards says. “It requires real vulnerability, which is a skill of strength.”

Richards, Denis Urubko and Simone Moro were descending when they heard the sound of thunder, a freight train and wind all at once

Thirteen years later, Richards remains the only American to climb any of the world’s 26,000-foot peaks in winter

The climb made Richards famous, his ice-covered face gracing the cover of National Geographic’s Milestone Issue 125

But all the magazine covers and lectures obscured not only his ongoing battle with extreme depression and bipolar disorder, but also his crippling PTSD, which would manifest itself in violent outbursts and a flight into alcoholism.

Then in 2020 he got a phone call that put him in the news again, but for the wrong reasons.

He was now sober, but in the past he was accused of sexual harassment. A drunken joke that plagued him again in the #metoo era.

National Geographic’s internal investigation was eventually concluded and Richards’ name was cleared, but there was no going back. And while the magazine decided to keep ties with its star photographer, he knew his career there was likely over.

A year later, while he was busy working on a film project about his life and was about to climb a new route on Everest, his life came crashing down in epic fashion.

He had spent days in his tent, sobbing. Lack of sleep, his thoughts spinning from nightmares about the avalanche to delusions to screaming into his sleeping bag until he was hoarse.

“I hug my legs to my chest and bounce my jaw on my knees, rock back and forth, and hold my head,” he writes. “I can’t stop crying, but I’m startled when I realize I’m crying at all.

‘At one point I start talking to myself in measured tones, reassuring myself that everything is okay. But eventually the only words that come out are, “I’m sorry” and “No, no, no.”‘

A crashed army helicopter on Gasherbrum II – evidence of the dangerous conditions on the mountain

During their descent they came across mummified bodies of people who had died in previous failed attempts.

All the magazine covers and lectures not only hid his ongoing battle with extreme depression and bipolar disorder, but also his crippling PTSD

After 40 hours without sleep, and just before attempting a new route on Everest, Richards realized he could not continue

By writing so honestly about his bipolar disorder and suicide attempt, Richards hopes to help reduce the stigma surrounding mental health issues

Knowing he could climb no further, he walked off the mountain alone, abandoning the film project, leaving his colleagues furious. Years of planning, tens of thousands of dollars, and an on-site film crew were all burned.

Back home in Colorado — broke, physically exhausted, his career in tatters and receiving angry emails from the people he had so disappointed — he Googled “how to tie a noose” and stood naked on a stool.

“I shower for between two minutes and an hour because I want to be clean when they find me,” he writes.

‘I put the rope around my neck and lean carefully against the noose.’

He describes the feeling he has when it becomes difficult to breathe and then, just before he passes out, the crutch tips over and he catches it with his feet.

He crawls away, shaking, realizing he doesn’t want to die. He just doesn’t want to live like this.

By writing so honestly about his bipolar disorder on Everest and his subsequent suicide attempt, Richards hopes to help reduce the stigma surrounding mental health issues and create more openness, particularly among men.

“I have spent most of my life trying to escape my own story of madness,” he writes. “I have chased the horizon, mistaking it for a perfect future where everything will make sense.

‘I chose to live like a madman to avoid the madness itself. I thought that by rebelling, by doing more, by being better, by being different, I could outshine, outdo, outdo the turmoil in my mind. But what if the noise and the madness were the gift?’

He adds: ‘Talking about pain, anger, frustration and all the rest is not weak and does not make anyone a ‘snowflake’. It requires real vulnerability, which is a skill of strength.

‘In silence we collapse. In silence we die.’

The color of everything: A journey to calm the chaos within by Cory Richards is published by Random House, July 9