Suicide prevention techniques ineffective as US sees increase in people committing suicide

Suicide prevention measures such as helplines, school programs and telehealth have not helped reduce the number of suicides in the US, experts warn.

Over the past two decades, federal officials have launched three national suicide prevention strategies that focused on addressing risk factors, providing aftercare, and evaluating at-risk groups such as Native Americans.

Despite these efforts, suicide is still rising in the U.S., up about three percent from 2021 to 2022, the most recent data available. In 2022, the number of deaths by suicide reached a record high of 50,000, driven largely by increases in depression.

Earlier this year, suicide surpassed Alzheimer’s and became the eighth leading cause of death among American men.

Despite several measures to reduce the suicide rate, mental health experts warn they have made no difference in preventing deaths by suicide.

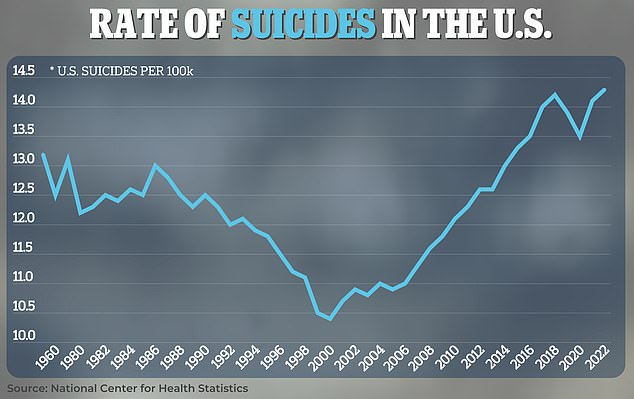

The US suicide rate hit a record high in 2022 at more than 14 deaths per 100,000 people

Pooja Mehta, a mental health and suicide prevention advocate in Virginia, told KFF Health News that despite national measures, it can be difficult to see that someone is having a hard time, making it more difficult to prevent suicide.

“We act like we know everything there is to know about suicide prevention,” she said. “We’ve done a really good job of developing solutions to some of the problem, but we really don’t know enough.”

For example, she said that when her 19-year-old brother Raj committed suicide in March 2020, some people blamed her for his death, saying her training should have helped her see the signs.

The government’s latest strategy, the Federal Action Plan, includes more than 200 actions to be taken over the next three years to reduce the number of suicides and treat those most at risk.

These measures include sending professionals to track patients when they call the 988 crisis line and preventing suicides related to substance abuse.

In addition, the plan calls for more suicide education in schools and programs for rural youth, such as 4-H.

Older strategies included plans for mental health follow-up care for those who had attempted suicide or decided not to. Examples include telehealth for therapy and access to medications.

But despite these measures, suicide is still on the rise in the U.S. In 2022, a record 49,500 adults died by suicide.

The latest data from the CDC also shows that suicides in the U.S. are more common than at any time since World War II.

The number of deaths by suicide also rose by three percent in 2022 compared to the previous year, preliminary data shows.

In 2021, there were 48,200 suicides, or one person every 11 minutes.

The numbers are particularly grim in rural states like Alaska, Montana, North Dakota and Wyoming, where deaths are up to twice as high as in urban areas.

CDC data shows that suicide rates increased 46 percent in nonmetropolitan areas between 2000 and 2020, compared to 27 percent in metropolitan areas.

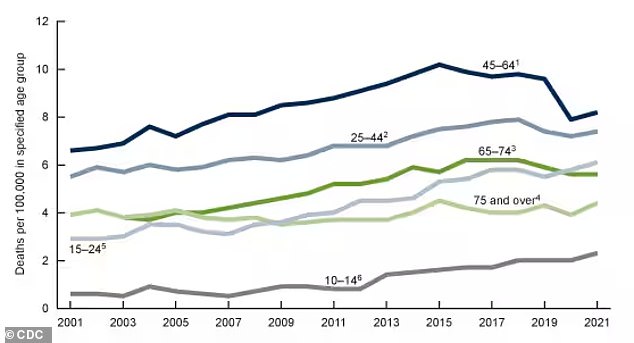

The line graph above shows the increase in suicides by age group, according to the latest CDC figures for 2022

Experts have noted that this could be due to higher poverty rates and a lack of therapists and other mental health professionals in these parts of the country.

Kim Deti, spokesperson for the Wyoming Department of Health, told KFF Health News that strategies like sending in crisis experts are promising, but they won’t be as effective in high-risk states like Wyoming.

“The work doesn’t stop, but some strategies that make sense in certain geographic areas of the country may not make sense for a state with our characteristics,” she said.

Furthermore, not all states have streamlined these measures. For example, one county may have a 24-hour mental health hotline, while the county next door may be open 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. And some states use law enforcement officers instead of mental health professionals, which can intimidate patients.

A poll of the National Alliance for Mental Illness and Ipsos It also found that only one in four Americans is aware of the 988 crisis line.