Stunning beach paradise in meltdown as marauding local surfer gang the ‘Bay Boys’ ‘attack tourists, strip naked in front of women and recklessly surf’

A Los Angeles County surf spot has become a hangout for a group of rowdy, experienced surfers who have been known to verbally intimidate visitors, show off their appearance and throw rocks at them.

The group, known as the Bay Boys, is also known for vandalizing cars, a lawsuit alleges. The lawsuit claims the gang has been doing this for decades and cites a crudely built fort beneath the cliffs of Lunada Bay as their base of operations.

The federal class action has been ongoing for decades and alleges that the surfers’ alleged antics violate the California Coastal Act.

The law requires that the public have access to sites along the state’s coast, which apparently isn’t the case at the foot of this hill on the edge of the wealthy town of Palos Verdes Estates.

So far, 12 members of the group have settled out of court — leaving just two left to fight claims from two surfers who say they were harassed. A hearing was held Tuesday — the latest in the long-running lawsuit.

Scroll down for the video:

The group known as the Bay Boys has operated out of their elaborate hangout (seen here) at the base of this hill along Palos Verdes Estates for decades, according to a lawsuit. During that time, they allegedly harassed visitors to keep them away.

Alleged victim Diana Reed said members of the group “flashed” her and sprayed her with beer while visiting the beach at the base of the cliff in 2016. She is one of the plaintiffs filing the lawsuit, alleging that she and others were illegally prevented from accessing the public beach.

“I was literally frozen with fear and couldn’t do anything,” alleged victim Diana Reed told KTLA about her alleged encounter with the “Bay Boys” when she was 29 and visited the surf spot in 2016.

“They were shouting all kinds of insults at me and making fun of me because my wetsuit was purple. They were treating me in a very rude and threatening way,” she said.

The Malibu resident filed a police report and returned to the coast a second time, where she says she was met with an even worse reception: two men immediately approached her.

“One of them immediately ran up to me with a can of beer, shook the can vigorously and sprayed the can of beer on my arm and my camera,” she recalled.

“The other man,” she said, “flashed her” — allegedly rubbing his genitals in a sexual manner.

“They said they were filming me because they thought I was sexy and I turned them on, you know,” she told the network, becoming emotional.

‘I try to forget all kinds of vulgar things.’

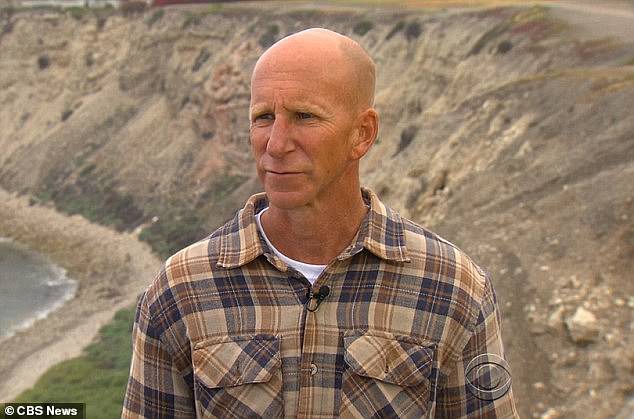

On Tuesday, another accuser, retired El Segundo police officer Cory Spencer, described his ordeal with the beachgoers, saying he was subjected to harassment from the group from a meeting place at the foot of the cliffs.

On Tuesday, another plaintiff, retired El Segundo police officer Cory Spencer, described his ordeal with the beach bums, which he said included being subjected to teasing from the group at their elaborate meeting place.

He claims that he was also harassed and even attacked by the elite group of locals in 2016, before being warned not to come near the stretch of beach.

“What the f**k are you doing here?” and “Why are you surfing here?” were among the jabs he received upon arrival, he said. The intimidation only got worse when he got into the water.

At that point, he told Judge Laurence Rubin of the California Court of Appeals, Second Appellate District, that one of the men, surfing the next wave, steered his board straight toward him while he was still paddling.

He remembered having to roll off his board to protect himself, and still cutting his wrist on the other man’s board.

Spencer also showed text messages sent by members of the Bay Boys in his part of the lawsuit, in which it appears that local surfers are happy to have the chance to harass him and an acquaintance after learning that the two are coming to visit.

“There are two madmen,” is said to have been written in one of the texts referencing Spencer.

‘[H]There is a little bald white man with them

‘[H]it looks like a bodyboard or f**k [sic] “What a joke!”

One of the elite people then confronted Spencer’s friend at their car on the hill where the pair were parked, asking him why they kept coming back.

“We’re going to make it hard for you every time,” said the man, one of the suspects who has since reached a plea agreement, according to Spencer.

“This is what we do. It’s not going to get better for you.”

They both allege that Palos Verdes Estates, a city of about 13,000, has avoided cracking down on the longstanding group, which has built a “rock fort” on the beach to hang out in. They also say the city hasn’t intervened because it’s fine with scaring off visitors.

Spencer, a lifelong surfer who also worked as an LA police officer, felt compelled to file a lawsuit, he said, paving the way for Reed to join the cause.

They both allege that Palos Verdes Estates, a city of about 13,000, has been reluctant to crack down on the long-standing group, which has built a “rock fort” on the beach to hang out in, the lawsuit says.

They say the city protects the band members as locals, but also appreciates them keeping outsiders out of town.

If the last two remaining surfers, identified in documents as David Melo and Alan Johnston, are found guilty of violating the California Coastal Act, they could face tens of millions of dollars in fines.

That’s because the fine for obstructing someone else’s access to public water ranges from $1,000 to $15,000 per day. That fine adds up considerably, even with the three-year statute of limitations from the start of the lawsuit in 2016 to now.

“If you harass someone with the intent to impede their access to the water, that is a violation of the Coastal Act,” Kurt Franklin, one of the attorneys for the District Attorney’s Office, told The slowness last week, claiming that the activity is still ongoing.

If found guilty, the last two remaining surfers, identified in documents as David Melo and Alan Johnston, could face tens of millions of dollars in fines. Lunada Bay, seen here, is located just south of LA in the wealthy city. It is known for its breathtaking views and great waves.

That’s because the fine for obstructing another person’s access to public water ranges from $1,000 to $15,000 per day — a figure that increases even with the three-year statute of limitations from the start of the lawsuit in 2016 to now. The top of the cliffs can be seen here

Last year, a California appeals court reopened the lawsuit, alleging that the city, as the landowner, had violated federal law by allowing a rock fort to be built on its property for decades without a permit.

As for the intimidation, the court ruled that this could also be in conflict with the Coastal Act.

The case is still pending in the California Court of Appeals.

Lunada Bay, on the other hand, is located just south of Los Angeles in the affluent Palos Verdes Estates and is known for its breathtaking views and great waves.