‘Strange’ bird species with teeth at the tip of its beak ate fruit instead of meat 120 million years ago in China, fossil analysis shows

With its beak full of super-strong teeth, this strange prehistoric bird might seem like a fearsome predator.

However, new research shows that when the Longipteryx chaoyangensis lived in China 120 million years ago, it actually fed on fruit instead of meat.

While it is often very difficult to determine the diet of an ancient animal, scientists at the Field Museum in Chicago were able to find fossilized fruits in the belly of this monster with its teeth.

This provides definitive evidence that Longipteryx did not feed on fish, as scientists previously thought. However, it is possible that the species also ate insects.

However, that does not mean that this feathered forager was harmless, as the researchers suspect that it may have used its sharp teeth to fight off other members of its species.

Researchers have discovered that the ancient bird Longipteryx chaoyangensis did not use its sharp teeth to eat meat, but actually lived on a diet of fruit

Lead author Jingmai O’Connor of the Field Museum said: ‘Longipteryx is one of my favourite fossil birds because it looks so strange: it has a long skull and teeth only at the tip of its beak.’

When the remains of this ancient bird were discovered in 2000 beneath what is now northwestern China, the teeth posed a major puzzle to paleontologists.

Based on its resemblance to the modern kingfisher, scientists initially suggested that Longipteryx may have hunted fish.

However, Dr O’Connor says the evidence for this theory was not entirely correct.

Because fish are often well preserved during fossilization, researchers have already found several ancient birds from a similar period with bellies full of fish.

However, no evidence of fish feeding was found in any of the Longipteryx specimens found.

When Longipteryx (pictured) was found in 2000, researchers thought the animal may have used its sharp teeth to catch fish

Paleontologists compared the ancient bird to a modern kingfisher based on the shape of its long, serrated beak

Dr O’Conor added: ‘What’s more, these fish-eating birds had lots of teeth, all along the length of their beaks, unlike Longipteryx which only has teeth at the tip of its beak. That just didn’t make sense.’

However, during a visit to the Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature in China, Dr. O’Connor noticed two specimens that appeared to have something in their stomachs.

On closer inspection, these turned out not to be fish or insects, but fruits from trees related to modern conifers and ginkgos.

Because Longipteryx lived in a temperate climate, researchers don’t think they ate fruit year-round.

Rather, they think they had a mixed diet, including insects, when fruits were not available.

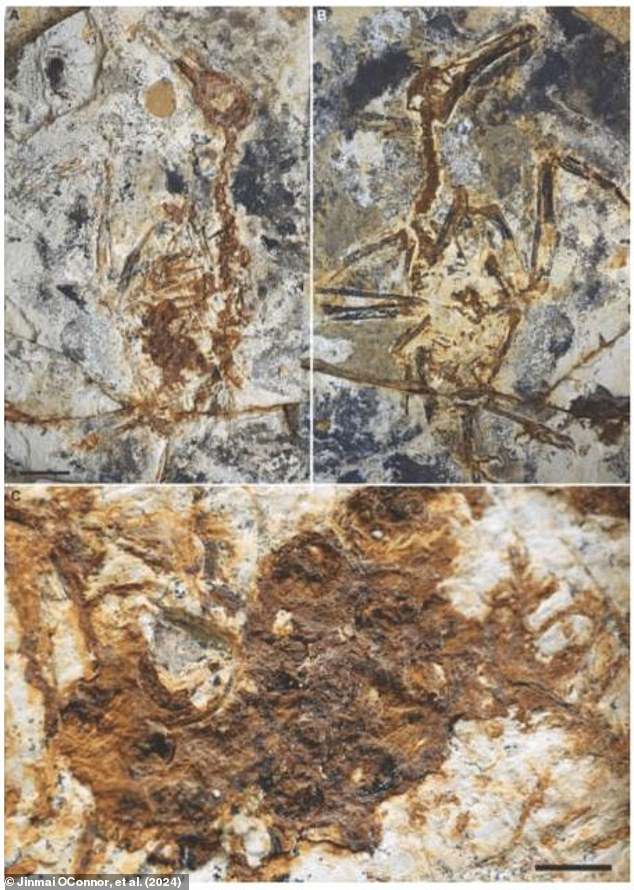

New analysis of fossils found in China reveals fossilized seeds (pictured) in stomach of ancient bird

Three fossils of Longipteryx (pictured) have been found eating fruits from trees related to modern conifers and ginkgos, providing direct evidence that they did not eat exclusively fish or insects.

Dr O’Connor added: ‘It’s always been strange that we didn’t know what they ate, but this study also highlights a larger problem in palaeontology: the physical features of a fossil don’t always tell the whole story about what an animal ate or how it lived.’

While researchers may have solved the mystery of what Longipteryx ate, the question of why the animal needed such large teeth remains unanswered.

Researchers discovered that each tooth of Longipteryx is covered with a layer of enamel 50 microns thick.

“That’s the same thickness as the enamel of huge predatory dinosaurs like Allosaurus, which weighed 1,800 kilograms, but Longipteryx is the size of a jay,” said co-author Alex Clark, a doctoral candidate at the University of Chicago.

Mr Clark adds: ‘The thick enamel is overwhelming, it looks like a weapon.’

While the fossils themselves don’t necessarily show how these weapons were used, scientists can take inspiration from modern animals.

Researchers think a better comparison for how Longipteryx used its beak is the modern hummingbird

Several modern hummingbirds have tooth-like projections near the top of their beaks (pictured left). The researchers think Longipteryx may have used its beak for fighting, like the hummingbird Androdon aequatorialis (right).

The researchers point out that several modern hummingbirds have tooth-like “keratinous projections” on the tips of their beaks, which they use to fight other hummingbirds.

Mr Clark says: ‘One of the most commonly used skeletal parts of birds for aggressive displays is the rostrum, the beak.

“It makes sense to have a weaponized beak because it keeps the weapon further away from the rest of the body and prevents injury.”

Because hummingbirds evolved these serrated weapons seven times, the researchers think Longipteryx used its teeth in a similar way.

This means that Longipteryx may have fed on fruit, but it also used its toothed beak to compete for resources such as food and access to mates.