Species that went extinct in the US after hurricanes hit the South

NASA predicts that all of the Florida Keys islands and their species will be swallowed up by the ocean this century as climate change raises global sea levels.

And now scientists and academics in the Sunshine State have confirmed the first local species to become extinct due to increasing hurricanes and rising sea levels.

The Key Largo tree cactus (Pilosocereus millspaughii) was eaten by local animals desperate for food and fresh water in the increasingly infertile, salt-saturated soil.

Since 2015, however, researchers have struggled to identify the thirsty tree cacti that are the culprits. For their new study, they set up months of camera surveillance on wildlife and studied the mysterious teeth marks on more than half of the now-extinct plant species.

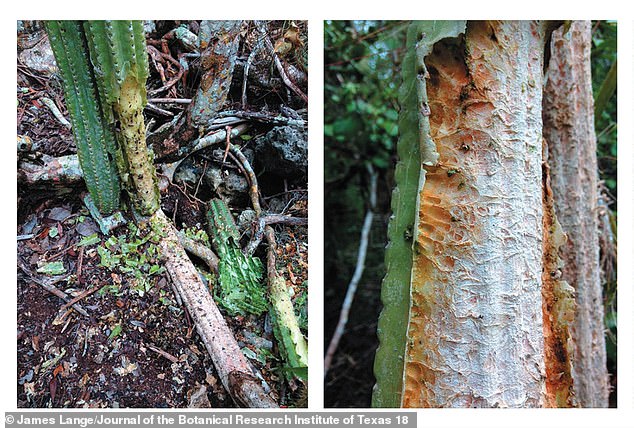

Scientists in Florida have confirmed the first local species being driven to extinction by increasing hurricanes and rising sea levels: the Key Largo tree cactus. Pilosocereus millspaughiidevoured by desiccated predators (above tufts of the long, woolly hairs that grow through the cactus)

In some cases, the marks from teeth and stripping of the plant for its precious freshwater supplies extended as far as four feet above the ground (as pictured above)

“We first noticed the big problem in 2015,” said researcher James Lange, who worked on the new study, “when we saw salt water flowing into the area during high tides.”

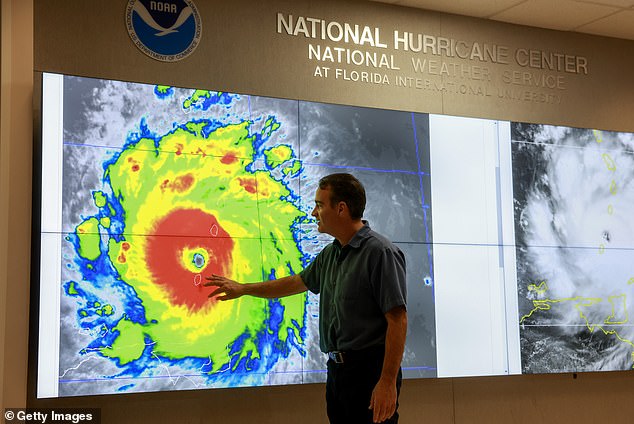

The tides that push into the Keys from rising sea levels and massive Category 5 storms like Hurricane Beryl “limit the amount of fresh water available to small mammals,” the botanist said, “and may be part of why herbivores targeted this cactus.”

Lange, who works as a field biologist at Miami’s Fairchild Tropical Botanical Gardenwarned that he and his research colleagues “cannot say for sure” what exactly prompted the wild, aggressive hunt for these cacti.

“We haven’t seen this level of cactus voracity anywhere in the Lower Keys,” Lange said, “where flooding tends to be less severe.”

And exactly which thirsty species are gasping for the water from the Key Largo tree cacti remained a mystery despite months of camera surveillance.

The researchers, working with Florida state wildlife officials, installed the cameras in 2016 after discovering in 2015 that about half of identified Key Largo cacti had been “eaten down to the vascular tissue.”

The characteristic teeth marks and the plundering of the plant for its precious freshwater supplies reached in some cases as much as four feet above the ground.

New damage from thirsty animals crushed cacti (left) and despite the visible teeth marks on these now-extinct Key Largo cactus trees, the exact species of animal that hastened the plant’s demise managed to evade camera traps for five whole months in 2016

The tides that are pushing into the Keys from rising sea levels and monster Category 5 storms like Hurricane Beryl (above) “limit the amount of fresh water available to small mammals,” says botanist James Lange, “and may be related to why the herbivores targeted this cactus.”

‘Of the 243 visits captured on camera, raccoons were the most numerous (58 percent), followed by birds (31 percent), marsh rabbits (5 percent), opossums (4 percent), and cotton mice (Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, Tuesday).

“Camera traps failed to capture any animals directly colliding with the cacti,” the researchers said.

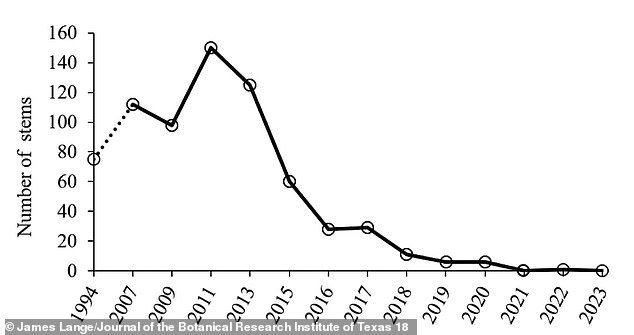

And yet, the following year, in 2017, this predatory behavior on the cacti had only expanded, resulting in deaths. “about another 50 percent of the population,” they wrote.

Lange and his colleagues at Fairchild worked with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to take cuttings from the remaining Key Largo cacti, hoping to nurse as many of the specimens back to health in greenhouses as possible.

But this failed attempt means that many unique and beautiful features of this rare species will likely no longer be seen in the wild.

Above is an image of the towering Key Largo tree cactus in healthier and happier times

“The climate emergency,” said a statement from the Florida Museum of Natural History, which collaborated on the new study, “has killed the Key Largo tree cactus that grows naturally in the U.S. through saltwater flooding and soil depletion from hurricanes.”

“The most striking difference is the tuft of long, woolly hairs at the base of the flowers and fruits,” says Alan Franck, current herbarium collection manager at the Florida Museum of Natural History, which has a collection of Key Largo forest specimens.

The hairs on the tree cacti are so thick that during the flowering period it looks as if the cactus is covered in snow.

But desiccated predators were just one factor that accelerated the cacti’s demise, the new study finds.

Nearly every acre of the islands that make up the Florida Keys (90 percent) is just five feet above sea level. According to researchers, the entire archipelago is at risk of disappearing by 2100.

Increasing soil salinity and strong hurricane winds have already caused much damage to the local ecosystem, especially to these cacti.

In 2007, annual soil salinity surveys around the dying cacti began. An earlier survey led by the Fairchild Botanic Garden found that soil salinity was higher under the dying Key Largo cacti.

“The climate emergency,” said a statement from the University of Florida’s Florida Museum of Natural History, which helped conduct the new study, “has driven the Key Largo tree cactus native to the U.S. to extinction due to saltwater flooding and soil depletion from hurricanes.”