Sorry ladies, men really are better at navigating! Research confirms that boys as young as 3 give more accurate directions than girls

If you have particularly bad luck navigating from the passenger seat, you’re not alone.

But new research shows that this is a feminine trait rather than a masculine one.

Psychologists in New Jersey have discovered that boys between the ages of 3 and 10 give better directions than girls of the same age.

The experiments showed that the males gave more accurate verbal instructions to a friend while navigating a computer-generated route.

Although the study focused specifically on juvenile animals, the findings may provide insight into gender differences in navigation that persist into adulthood.

The study found that boys gave more helpful and accurate directions than girls, suggesting that boys have better spatial awareness.

The new study was led by researchers at Montclair State University in New Jersey and published in the journal Journal of Experimental Child Psychology.

Lead author Yingying Yang said there are several theories about why boys give more accurate directions.

‘These range from biological (e.g. testosterone) to experiential (e.g. boys have more experience of travelling independently) and parenting practices (e.g. boys are allowed to travel further from home than girls),’ she told MailOnline.

“Unfortunately, our research does not test any theories about why this happened.”

For their online experiment, which was conducted via Zoom, the researchers recruited 141 volunteers aged 3 to 10 years: 78 boys and 63 girls.

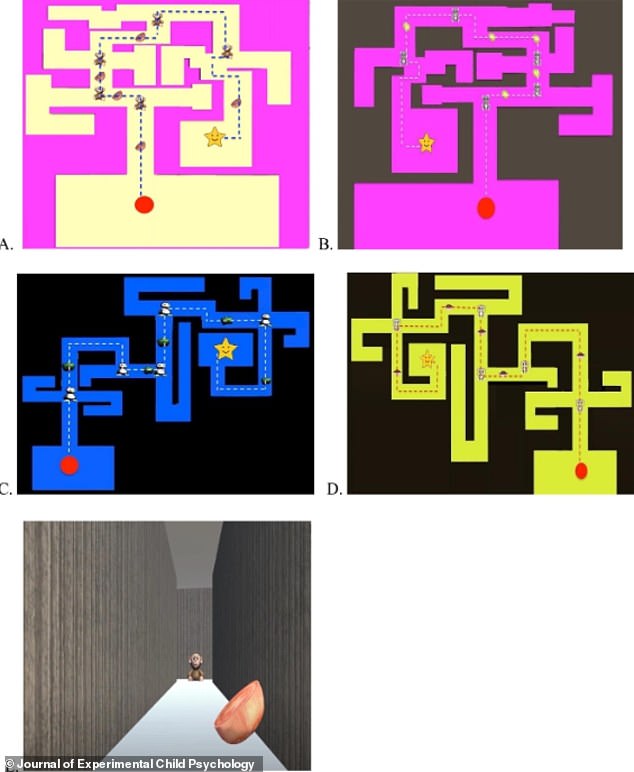

Using a computer program, the children had to describe a route, both from a bird’s eye view (‘map’) and from the first person perspective, which gradually moved through the corridors of a ‘maze’.

Along the route were ‘landmarks’: small objects in the style of a computer game, such as a mango, a teddy bear, a monkey and a bowl of cherries.

Using a computer program, the children were instructed to describe a route, both from a bird’s eye view (‘map’, AD) and from a first-person perspective (‘maze’, E).

In both situations they had to guide a computer-generated friend called ‘Mr Birdie’ – who was blindfolded and unable to see – through the route using verbal cues.

Researchers assessed the directions the children took based on how well they used useful directional cues (e.g., left and right) and landmarks (monkey, cherries) to describe the routes.

The results showed that boys were generally better at giving correct directions (e.g., “turn left”) and less likely to give vague directions (e.g., “that way”).

Later in the experiments, the researchers asked the children to recall the directions along the route, purely from their own memory.

But in this case, the academics found that boys and girls performed similarly, suggesting that both are equally good at remembering routes.

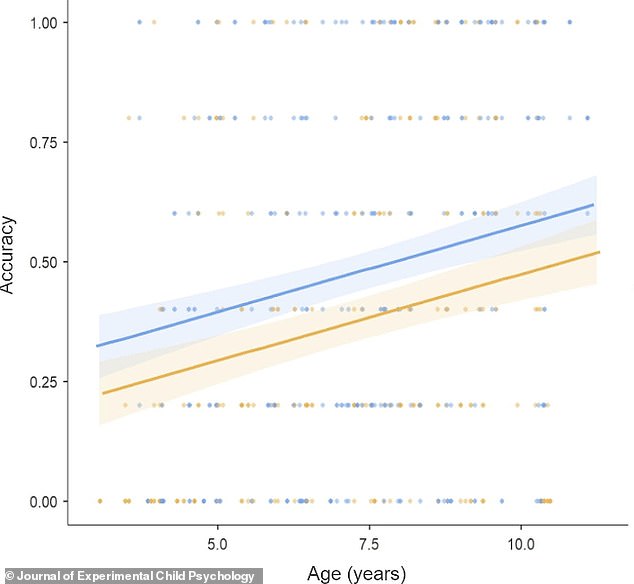

In general, boys were more accurate in describing routes than girls, as this graph shows. However, boys and girls were about equally good at remembering the route.

Interestingly, the researchers also found that the clues were generally given better in the map condition than in the first-person maze condition.

This suggests that maps are indeed a better way to teach children a route than physically taking them along that route.

“To help children find their way better, it may be more useful to teach them to use maps than just showing them a route,” the team said.

Their findings may be important for understanding individual differences in navigation in children and may also help close the gender gap, especially in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) subjects.

A limitation of the study is that the team was unable to code hand gestures and analysis was limited to verbal utterances.

a Study from 2018 found that in young children and adults, approximately 30 percent of verbal sentences were accompanied by gestures when asked to give directions.