Ski holidays in the Alps could be a thing of the past, scientists warn – figures show snowfall has fallen by a THIRD since 1920

It is one of the world’s most popular ski destinations and home to some of the most prestigious resorts.

But scientists warn that ski holidays in the Alps could soon become a thing of the past.

Scientists at Eurac Research found that snowfall fell by a third between 1920 and 2020.

In some regions the situation is even more dire, as data shows emissions have fallen by almost 50 percent on the southwestern slopes.

Although the data goes back a hundred years, snowfall only started to decline sharply from 1980 onwards.

The researchers note that this coincides with a sharp increase in average air temperature around the world due to human-induced climate change.

In the worst affected regions in the Southern Alps, including Italy, Slovenia and Austria, these changes could threaten the future of winter sports.

Lead researcher Michele Bozzoli says: ‘The decrease in snowfall not only impacts winter sports, but also all activities and processes that depend on water.’

Ski holidays in the Alps may be a thing of the past as researchers discover snowfall has fallen by a third over the past hundred years. This map shows 46 locations in the Alps, red arrows show areas where snowfall has fallen by more than 30 percent

There are growing concerns that skiing in the European Alps will become impossible as the number of days with snow cover decreases. This was the scene at the closed Dent-de-Vaulion ski lift on February 2, amid a lack of snow at altitudes below 1500 meters

With an estimated 400 million people visiting ski resorts around the world every year, snow is an absolutely essential part of the tourism economy.

When the snow melts during the ski season between December and April, resorts have no choice but to run shorter, less profitable seasons.

There is now growing concern around the world that climate change is making it impossible to keep the slopes open.

In their new study, researchers collected a century’s worth of snowfall data from 46 locations in the Alps by combining recordings from modern weather stations with handwritten notes from the early 20th century.

This has provided, for the first time, a comprehensive picture of how snowfall has changed over the past 100 years.

Mr Bozzoli said: ‘There is a clear negative trend in terms of fresh snowfall in the Alps, with an overall decline of around 34%.

‘A remarkable decline was observed, especially after 1980. This date also coincides with an equally strong increase in temperatures.’

From 1980 onwards, the average air temperature measured by weather stations began to rise rapidly, reaching values almost 1°C (1.8°F) above the 100-year average.

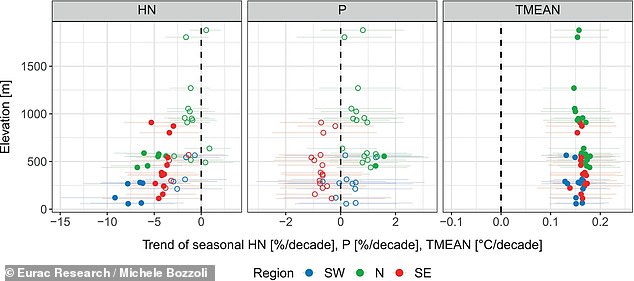

The decline in snowfall in the Alps (left graph) relative to the 100-year average (dashed line) was accompanied by a sharp increase in average air temperatures (right graph) that began in the 1980s due to human-induced climate change

Resorts at lower altitudes and in the warmer southern areas of the Alps were hit harder, as rising temperatures caused precipitation to fall as rain rather than snow. Pictured: Skiers try to make the most of conditions as France’s Lans en Vercors ski resort has no snow on January 27

Those warmer temperatures prevent snow from forming at lower elevations and precipitation instead falls as rain.

Despite an increase in total precipitation, this means that annual snowfall has declined sharply, especially in warmer regions and at lower elevations.

The Southwest and Southeast regions showed an average loss of 4.9 percent and 3.8 percent respectively each decade.

Northern regions, meanwhile, showed a smaller but still worrying loss of 2.3 percent per decade.

Mr Bozoli says: ‘The most negative trends concern locations below 2,000 meters and are in southern regions such as Italy, Slovenia and part of the Austrian Alps.’

At higher elevations, sufficiently cold temperatures mean snowfall levels have remained largely consistent.

However, data shows that temperatures in the southwestern and southeastern Alps have now risen so much that rain regularly takes over snow even at higher altitudes.

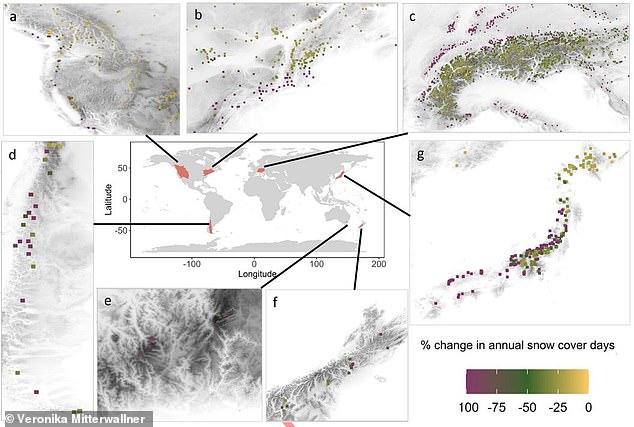

Previous studies have shown that climate change is putting a number of ski resorts around the world at serious risk of being snowless by the end of the century.

Previous research suggests that ski resorts in the Australian Alps (pictured) may no longer be economically viable as the number of days with snow cover could fall below 100 days

Earlier this year, researchers found that one in eight ski resorts in the world would have no snow between 2071 and 2100.

The worst affected region is expected to be the Australian Alps, which will receive only 38 days of snow per year.

Even the European Alps, where 69 percent of the world’s ski resorts are located, are expected to have 42 percent fewer snow days by 2100.

Also earlier this year, the iconic slopes of Mount Fuji remained snowless for the longest time in 130 years of records.

Snow didn’t fall on Japan’s highest peak until early November, a month later than the usual date of October 2.

The situation is so dire that many resorts are forced to store snow in large isolated reserves during the summer to replenish the slopes during the following season.

However, the authors of this latest article warn that declining snowfall in the Alps will ruin more than a few ski holidays.

Snow plays a crucial role in maintaining alpine ecosystems and protecting mountainous settlements from flash floods.

This map from a previous study shows how each ski area will be affected by climate change by 2100. The purple squares show areas that will not see snow-covered days, while the yellow dots show regions that will not be affected.

When precipitation falls as rain instead of snow, it can quickly drain down steep mountain valleys, leading to increased erosion and greater flooding.

Research conducted last year at Colorado State University found that rain-induced flooding was twice as large as flooding caused by snowmelt.

Mr Bozzoli concludes: ‘Snow is crucial as a water reservoir, it feeds glaciers and mountain streams and, because it melts slowly in the spring, gradually replenishes water reserves.

‘This aspect can no longer be ignored in water management policy planning’