Six years ago, inheritance tax was criticised as a shambles – and it has only gotten worse since then, says SIMON LAMBERT

Imagine this. The government commissions an official report on a high-profile tax. What comes back is a comprehensive report that is as damning as you can imagine, labelling the structure as unfair, critical benefits as outdated and calling for an overhaul.

Six years later, nothing has been done to resolve that tax.

But you don’t have to imagine this scenario, because this is what actually happened with the inheritance tax.

Stacking: Inheritance tax was originally intended as a levy on the estates of the very rich, but has increasingly become a tax on the affluent middle class who own family homes in the south of England.

This is exemplary of the total failure of the British tax system over the past two decades.

Successive finance ministers knew about bad taxes that were damaging public confidence, but instead of fixing them, they not only ignored the problem, but often made it worse.

The Tories made a lot of noise about improving the burden of inheritance tax and even hinted at scrapping it. Apart from George Osborne’s fiddling with the clumsy home exemption, they ignored the problem.

Conservative chancellors have been happy to sit back and allow inheritance tax to become more and more of a tax grab on the affluent middle class rather than the levy on the very rich that it was intended to be. Now we are in a bad position to start with, faced with a Labour Party that seems keen to tax wealth.

In January 2018, then Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond asked the Tax Simplification Office to conduct a review of inheritance tax with the aim of simplifying it for both the government and taxpayers.

At the end of 2018, the OTS presented the first part of the evaluation, followed by the last part in 2019.

As I indicated above, the findings of the study were far from positive.

It painted a picture of a complete shambles of a tax which, despite being paid by only a small percentage of estates, creates an administrative nightmare for many more whose loved ones have died, and cements the tax’s reputation as Britain’s most hated tax.

In November 2018, the OTS said: ‘Although inheritance tax is payable on less than 5 per cent of the estates of the 570,000 people who die in the UK each year, around half of families have to fill in the forms.

‘Many also told us that their relatives were concerned about inheritance tax during their lifetime, even though they themselves would not be affected by it.’

Inheritance tax is charged at 40 per cent on estates above the individual exemption threshold of £325,000, with an additional tax-free amount of £175,000 for estates leaving their own home to direct descendants.

You can pass your unused exemptions on to your partner. This means that married couples and civil partners have a combined exemption of £1 million.

One of the cornerstones of inheritance tax is to limit the amount that people whose estate is subject to tax may give away before the gifts end up in the inheritance tax net.

If they exceed this gift limit, they must survive for another seven years before the gift becomes tax-free.

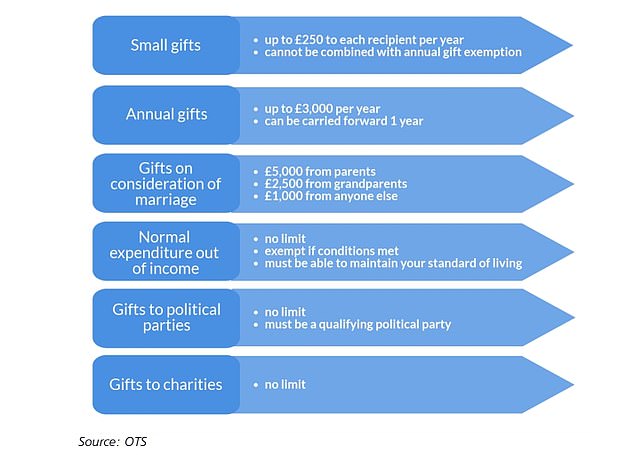

The OTS emphasized in detail how outdated these limits are and that they have not been increased since the introduction of inheritance tax in its current form in 1986.

The frozen gift limit means you can only give away £3,000 each year before potentially incurring an inheritance tax liability.

There is an exemption for weddings: a parent can give £5,000 and a grandparent £2,500.

You can also create an unlimited number of small gifts worth up to £250, but you can only make one per individual recipient.

There is an exemption from IHT for making regular gifts from surplus income, but this is a murky area and you cannot use it to give away your savings.

The rules for gift giving create some truly bizarre potential scenarios for someone unlucky enough to die within seven years.

- Your estate may be liable for inheritance tax if you:

- Buy your 18 year old a £5,000 used Ford Fiesta

- Split your daughter or son’s wedding (the average cost of which is said to be £20,000)

- Have you already given away your £3,000 this year and are buying your grandchild a school laptop?

- Take the family on a big vacation

Once upon a time: Inheritance tax gift limits have not changed since the 1980s

Despite all these restrictive rules, the really rich pay a lower effective inheritance tax rate than the merely wealthy

In reality, I can imagine that these kinds of things happen often and that no inheritance tax is levied on them, even if the donor dies within seven years.

Theoretically, the tax authorities could recover 40 percent of an inheritance above the inheritance tax threshold on all of the above matters.

One situation where people are at greater risk of an IHT bill is where the Bank of Mum and Dad (or Gran and Grandad) has helped with the down payment on a house, often amounting to tens of thousands of pounds.

One of the most striking elements of the OTS report was that despite all these restrictive rules, the really wealthy pay a lower effective rate of inheritance tax than those who are simply wealthy.

The standard exemptions of up to £1 million per married couple mean that the effective total rate of inheritance tax on estates (the amount paid relative to its value) is much lower than the standard rate of 40 per cent.

As people enter the IHT net, the effective rate rises steadily, from 5 per cent at the bottom, to around 20 per cent for estates of £2 to £3 million, and remains the same up to around £7 million.

But after that it starts to decline and by the time you have an estate of more than £10 million, the effective inheritance tax rate is 10 per cent.

In this case, it pays to have enough money to plan well for inheritance tax. For example, exemptions such as passing on businesses and farmland are used by the wealthy, rather than the entrepreneurs or farmers they are intended for.

In its second report, the OTS made 11 recommendations. The most important for the majority of people were those dealing with lifetime gifts, where a new, simpler general personal gift exemption at a higher level was recommended, together with a reduction of the seven-year rule to five.

I believe that inheritance tax could be even simpler. Reduce the IHT rate to a much more agreeable 20 percent. The tax revenue would remain the same, but it would be less rewarding to avoid tax.

Readers of This is Money disagree. In a poll of more than 2,500 people, only 10 percent were in favor of lowering the rate. 26 percent wanted to raise the threshold and 51 percent wanted to abolish it altogether.

Only 8 percent thought that it was either fair as it is, or that people should pay more tax on inheritances.

Whatever your views on inheritance tax, you would think that after such a damning report on a tax that is way above its prime in terms of attention and disruption, something would have been done.

Instead, the Conservatives sat on the OTS report for so long that it outlasted the Office for Tax Simplification itself, which was abolished by Kwasi Kwarteng and Liz Truss.

As with many of our problematic tax traps, it’s a shame the Tories never took action.

Especially as our new Labour government, for some bizarre reason, wants to crush economic optimism with tax increases.

Maybe we’ll get a surprise in October. Maybe Rachel Reeves won’t stage a sad inheritance tax attack that makes a bad tax worse, but instead increase gift tax exemptions to bring them into line with modern life and make it simpler and better.

I don’t think that will ever happen.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them, we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow commercial relationships to influence our editorial independence.