Should you worry about measles sweeping Britain? Case numbers are higher than at any time since the 1990s and have more than doubled in a year amid outbreaks in London and the Midlands. This way you can protect yourself

What is measles?

Measles is a highly contagious disease caused by a virus. It infects the respiratory tract and then spreads throughout the body. It can cause serious illness, complications and even death. Although measles can affect anyone, the disease is most common in children. Complications can include chest and ear infections, diarrhea, encephalitis (infection of the brain), and brain damage. Complications are more common in certain groups, including people with weakened immune systems, infants under one year of age, and pregnant women. Those who develop complications may need to be hospitalized for treatment.

How do you catch it?

Measles is contracted through direct contact with an infected person. It spreads easily when an infected person breathes, coughs or sneezes.

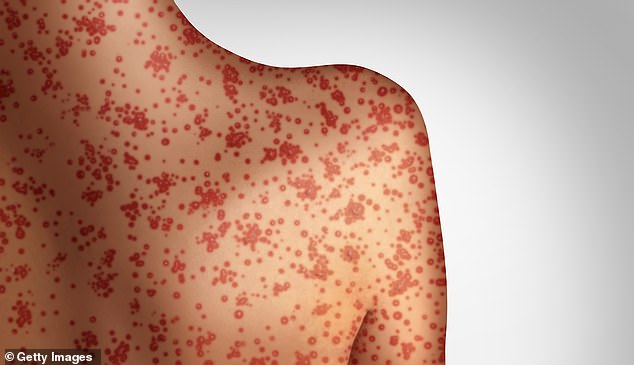

What are the symptoms?

Measles usually starts with cold symptoms, followed a few days later by a rash. Typical symptoms include high fever, coughing, runny nose and rash all over the body. Some people may also develop small spots in their mouths. Symptoms usually develop nine to eleven days after you become infected and last up to fourteen days from the first signs to the end of the rash. There are no specific medications for measles, so treatment is intended to relieve symptoms and address complications.

How contagious is measles?

Extreme. Each patient typically passes the viral infection on to 20 others. If you are not protected and have had even brief contact with someone who has measles, there is a good chance that you will also become infected. If someone has not been vaccinated or has become immune through a natural infection and lives in the same household as someone with measles, there is a 90 percent chance that he or she will get measles themselves.

Why are people concerned?

The number of suspected measles cases has doubled in a year, with outbreaks currently being reported in London and the West Midlands. Figures from the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) show that there were 1,603 suspected cases of the disease in England and Wales last year, up from 735 in 2022 and 360 in 2021. The suspected cases are based on official reports from doctors diagnosing based on clinical symptoms. . Later laboratory tests do not confirm that it is measles. But it is clear that the number of cases is increasing. Levels in the West Midlands are now the highest since at least the mid-1990s, with 57 suspected cases in the last four weeks of December alone – a quarter of the total of 217 for the whole of England and Wales. On Friday, Birmingham Children’s Hospital said it had treated 50 children for measles in the past month, the most in years. At least 167 laboratory-confirmed cases and a further 88 probable cases have been reported in the West Midlands. Meanwhile, London reported 44 cases from the same period, with cases reported throughout the year. It comes after the UKHSA warned earlier this year that London was facing an outbreak of between 40,000 and 160,000 due to low vaccination rates. For every 1,000 people infected, between one and three will die, with those under the age of five and with weakened immune systems most at risk.

Why does this happen?

Britain lost its measles-free status three years after eliminating virus transmission in the country, due to falling vaccination rates. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was a decline in uptake due to false claims that the MMR vaccine was linked to autism. But efforts to increase vaccination rates worked and led to the World Health Organization declaring Britain measles-free in 2016. But this has not been enforced, meaning measles is now circulating within our communities again. The pandemic caused some children to miss out on routine vaccinations, with numbers still not catching up. Uptake of both doses of the MMR vaccine is about 85 percent nationally – well below the 95 percent needed for herd immunity. This figure falls much lower in some areas with larger ethnic minority populations, making them more susceptible to outbreaks. Vaccine hesitancy may also be a contributing factor, while pressure on primary care and a reduction in the number of health visitors are also likely to lead to lower vaccination rates.

The number of suspected measles cases has doubled in one year

How do we protect ourselves against measles?

Measles is extremely contagious. To achieve herd immunity against measles, it is necessary for at least 95 percent of people to be immune to the disease, usually through vaccination. Vaccination programs are essential to prevent measles and a highly effective vaccine is available as part of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) jab. Babies are offered the first dose at 12 to 15 months of age and a second dose is usually given from three to three and a half years and later.

I haven’t had mine, what should I do?

If missed, it can be given at any age. Anyone who has not yet had two doses of the MMR vaccine should ask their GP for a vaccination appointment. The NHS advises anyone planning a pregnancy, traveling abroad, starting university or working in healthcare to check that they have had both doses. A definitive infection from the past will also protect against future infections. Pregnant women or women with a weakened immune system should not be immunized.

How soon should a child return to school after having measles?

Measles is most contagious from four days before the rash appears until four days after. Doctors recommend that a child should be kept out of school for four days after the results start.