Should you wait until after the elections to sell your home? What real estate experts say

Homeowners looking to sell would be better off doing so before the next general election, according to new research published by estate agent Winkworth.

While we don’t yet know when that will be, those planning to move may be concerned that any policy changes or general uncertainty could affect their plans.

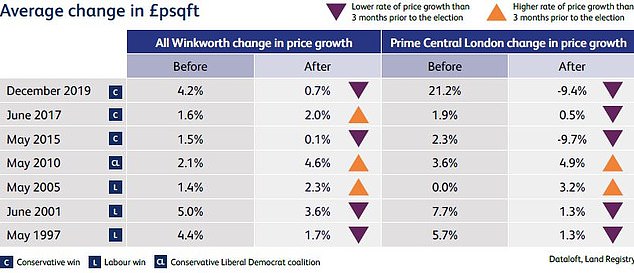

The research, carried out by analysts Dataloft, looked at changes in house prices before and after the seven previous general elections, in the regions where Winkworth has offices.

That includes Greater London, the South East, the South West, East Anglia and Northamptonshire.

In those areas, it found that property price growth would fall rather than rise in the three months after the country went to the polls.

All photos from Getty Images: Credit from left to right – Photo by Colin Davey. Anthony Harvey, Scott Barbour, Matt Cardy. From bottom left to right – photo by Sean Gallup, Mustafa Yalcin/Anadolu Agency, Nicolas Economou/NurPhoto and Stefan Rousseau

Looking at the most recent election in 2019, it appeared that the so-called ‘Boris bounce’ in the property market after the last general election did not yield any results.

In the three months leading up to the December 2019 election, in which Johnson’s opponent was Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn, average British prices rose by 4.2 percent.

However, in the three months after the elections, average prices rose by only 0.7 percent. In central London, prices fell by 9.4 percent in the three months after Boris’s election.

Dominic Agace, CEO of Winkworth, said: ‘The effect of a general election is to distract people in the three months leading up to election day.

“Politicians pursue policies to win votes, and the politics can be more extreme than the reality of what happens once a party is in power.”

Prices rose by almost the same percentage before Tony Blair’s victory in 1997, at 4.4 percent, before falling to 1.7 percent in the three months after.

The study looked at house price changes over three months before and after the last seven elections in London, the South East, the South West, East Anglia and Northamptonshire.

House price growth also slowed after the 2001 elections, when Blair won again, and in 2015 when David Cameron’s Conservatives gained exclusive control after five years in coalition.

However, in the 2005, 2010 and 2017 elections, prices rose faster in the following three months.

In the three months leading up to each of the last seven elections, the average price per square meter rose by a total of 20.2 percent, Winkworth said.

Meanwhile, the price per square meter increased by a combined 15 percent in the three months after the elections.

Winkworth’s experts say this mixed picture suggests that elections may not be the main driver of price developments – and that ‘waiting to put a property on the market after an election, in the hope of achieving a much higher price, is a risky strategy could be’ .

The Boris dip? The research shows that the so-called Boris bounce in the property market after the last general election has failed to deliver

The data, which are based on figures from the Land Registry, have some limitations. Data from the Land Registry is based on sales prices and may therefore relate to sales that were agreed months before they appeared in the register.

This means that houses sold in the three months after the election could be agreed before the election, and houses sold before the election could be agreed up to six or more months before the election.

What does house price data in Britain say?

We decided to look at the Land Registry figures for the whole of Britain and see what prices were doing in the years before and after the previous seven general elections.

These figures include homes sold across Britain, not just the South of England.

This analysis suggests that house prices are more likely to do better after an election than before.

Taking into account each year leading up to the last seven elections, house prices have risen by a collective 44 percent, giving an annual average of just over 6 percent for each year before the general election.

However, in each year since the last seven general elections, house prices rose by a collective 53 percent – for an annual average of just over 7.5 percent.

Ultimately, house prices are more likely to be influenced by other factors than a general election.

For example, in the year after Boris Johnson’s election in December 2019, house prices across Britain rose by 6.99 percent.

Rather than being due to a Boris revival, this is more likely due to the stamp duty holiday that started in July 2020 – alongside the race for space and the house-moving boom that started during the pandemic.

Do elections slow down housing market activity?

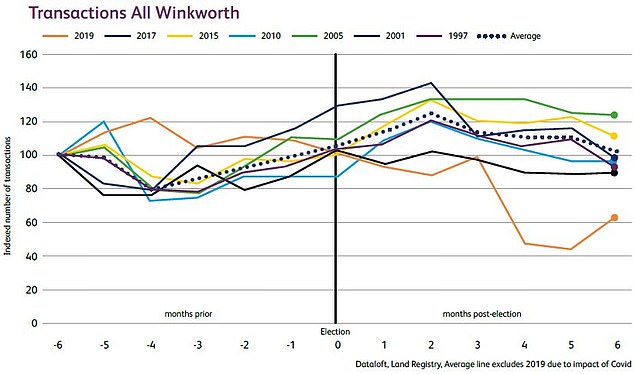

In addition to changes in home prices, Winkworth’s analysis also found that uncertainty leading up to the election has a short-term effect by slowing the number of sales in the three to four months before voting day.

It turned out that this pattern held true for six of the last seven elections.

Once the election results are known, increased certainty about the political landscape and policies will normally allow markets to regain strength.

However, Dataloft’s report also suggests that the time of year may have more influence than the fact that there is a general election.

Transaction hit? Pre-election uncertainty has short-term implications for slowing sales in the three to four months before voting day

Delaying the sale or purchase of a home until after the election could mean missing out on the best time of year on the real estate calendar, with spring typically being the best time for home sales.

The report shows that over the past five years (excluding 2020 due to Covid), 27 per cent of sales occurred in spring, the highest of any season, according to HMRC figures.

During the same period, it took an average of just 51 days to sell properties, compared to 61 days in winter.

Will the upcoming elections already have an impact on the market?

Jeremy Leaf, a north London estate agent and former chairman of the Rics residence, believes the uncertainty associated with elections always causes some people to wait before buying or moving.

However, with the upcoming elections, he hasn’t noticed people changing course yet – probably because the date has yet to be announced.

“Elections have been a factor in decisions to buy and sell homes because they tend to create uncertainty, especially as we approach the expected date,” Leaf says.

Ed Davey (left), Rishi Sunak (centre) and Sir Keir Starmer (right) want their party to be seen as the best choice for homeowners, first-time buyers and renters

‘If the bookmakers are to be believed and there is a change of government, Labour’s statements to date have indicated a pro-business and especially pro-construction strategy, which, if implemented, is likely to only benefit the housing market in terms of improvement. the number of transactions, if not the prices.

‘If anything, it is likely to be higher value transactions and high net worth individuals that are most likely to get into trouble for the tax authorities, rather than the more mundane transactions, which make up the vast majority of those that take place.

‘However, we have seen no decline in demand or interest from UK or foreign investors in buying UK property in recent months and do not expect this to change, even if they proceed cautiously without building in. too much potential profit.

“Most people don’t hesitate, change their minds or wait for the outcome of the election, although that may change as the date approaches.”

Sam Mitchell, CEO of online real estate brands Strike and Purplebricks, says there is a danger that as the election approaches, people will put off their plans until after the result.

This could be exacerbated if each party makes housing commitments, such as pledging to reduce stamp duty or capital gains tax.

“We expect a period of positivity between now and the general election, with the market remaining strong, with house prices continuing to rise month on month and buyer demand increasing,” Mitchell said.

“In light of the faster-than-expected decline in inflation and expectations that rate cuts will start to be priced in from June, we can be optimistic about housing market activity in the coming months.”

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on it, we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow a commercial relationship to compromise our editorial independence.