Disturbing twist after Cooper Onyett dies on school camp

The parents of a young boy who nearly drowned during a school camp just minutes before another student was tragically killed are suing the state government and an aquatic center.

Brad and Pearl Sutton’s son, who cannot be named, almost drowned while at Belfast Aquatics in Port Fairy in south-west Victoria on a trip organized by Merrivale Primary School in Warrnambool.

They claim their eight-year-old son struggled to stay afloat in the water after jumping from the inflatable rig into the deep end.

“He couldn’t keep his arms above water, all you could see were his hands sticking out.” Mr Sutton told the Herald Sun.

The parents of a young boy who nearly drowned during a school camp just minutes before another student was tragically killed are suing the state government and an aquatic center.

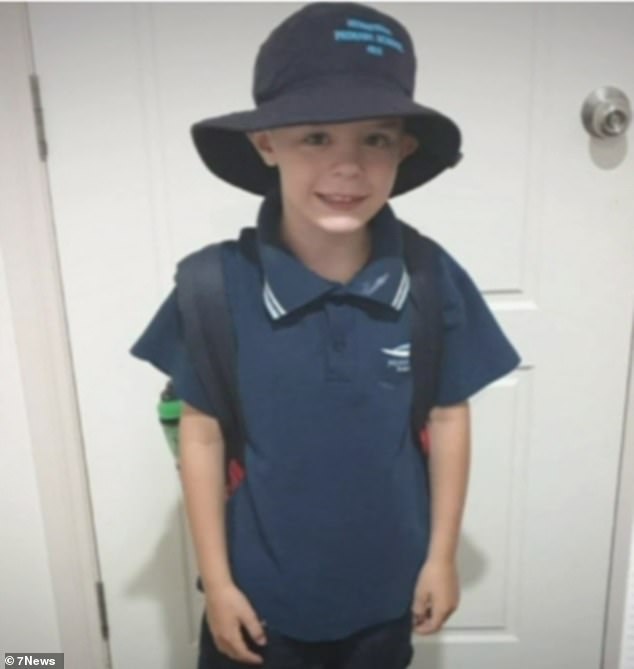

The harrowing incident happened just five minutes before year two student Cooper Onyett (pictured) drowned during the same school camp

“He was underwater for a long time, he thought he was going to die that day.”

Mr Sutton said his son’s glasses soon began to fill with water and he could not hold his head up.

“I tried to hold on to the bouncy castle but it was so slippery I couldn’t get a grip on it,” Mr. Sutton recalled his son saying.

A woman swimming at the other end of the pool saw the boy struggling in the water.

She immediately alerted nearby teachers and staff, who quickly helped the boy out of the pool.

Mr Sutton explained that the school required parents to complete a consent form detailing their children’s swimming skills. On this form he clearly indicated that his son could not swim.

Mr and Mrs Sutton are now suing the Victorian Government and Port Fairy Community Pool Management Group, which runs Belfast Aquatics, for negligence, according to legal papers filed in the High Court.

The parents plan to claim damages and other costs resulting from the incident.

Mr Sutton said he hopes this will prevent other families from facing a similar situation.

The harrowing incident happened just five minutes before year two student Cooper Onyett drowned during the same school camp.

The Department for Education pleaded guilty to charging WorkSafe with ‘failing to ensure that persons were not exposed to risk’ after the little boy died at the school camp.

The swimming center has reportedly pleaded guilty to the charges filed by WorkSafe last Wednesday.

Last Thursday, the Warrnambool County Court heard the school sent consent forms and medical forms to parents before the trip, asking how far their children could swim.

Cooper’s mother Skye checked a box and confirmed he is a novice swimmer with little or no experience in shallow water, prosecutor Duncan Chisholm told the court.

However, the school never passed on information about students’ swimming skills to the pool before sending 28 young students there.

The year two pupils were asked to raise their hands if they could swim when they arrived at the aquatic centre, Mr Chisholm said.

Children who said they could swim were led to an inflatable obstacle course in the deep end of the pool, but many were eventually identified as weak swimmers and helped to the shallow end, he said.

Cooper was one of the children identified as a weak swimmer and was spotted outside the shallow area twice more: he jumped into the deep end and onto the bouncy castle, from which he was told to get off.

A swimmer with her daughter later saw the boy floating underwater and initially thought he was holding his breath.

Cooper (left) is pictured with his mother Skye Meinen

“After about 40 seconds, she realized something was wrong,” Chisholm said.

Cooper died after attempts to revive him at the pool failed.

Victoria’s education department has pleaded guilty to breaching health and safety law after Cooper’s death and admitted it failed to ensure people other than workers were not exposed to risks.

“If information about the children’s swimming skills had been passed on to Belfast it could have reduced the risk of drowning,” Chisholm said.

During last Thursday’s plea hearing, Judge Claire Quin repeatedly asked government attorney Carmen Currie why the school collected information about the children’s swimming skills, if not to disclose it to the pool.

Ms Currie said the information was collected for planning purposes, and the department could not “anticipate in each individual case the exact information a provider might need” for a school activity.

It was poolside to request the information, the attorney said.

“The activity was swimming,” Judge Quin said.

“Why get the information if you’re not going to give it to the people who need it?”

Mr Chisholm said the department was relying on someone else to meet its own obligations when it placed responsibility on the aquatic center to ask about students’ swimming skills.

“When they drop kids off, they don’t just throw them off the bus and say, ‘You’re right,’” he said.

Currie said the department has since made it mandatory for schools to tell swimming pools about their students’ swimming skills.

However, she said there was no evidence that disclosing the children’s swimming skills would have changed the way Belfast Aquatics managed the activity on May 21.

Port Fairy Community Pool Management has also admitted breaching health and safety legislation.”

Judge Quin is expected to sentence both the department and pool management on May 31.