Shocking bodycam footage shows moment Florida federal drug prosecutor Joseph Ruddy offers cops his business card during DUI crash

A prolific Florida prosecutor tried to offer police his business card to avoid being arrested for drunken driving after attacking an SUV on the Fourth of July.

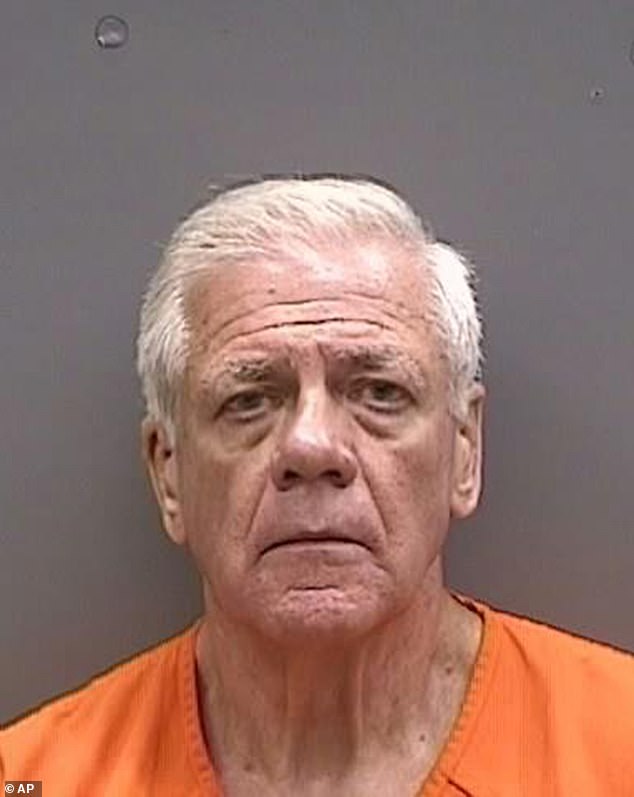

Joseph Ruddy, 59, a federal prosecutor, was stopped by police outside his home in Tampa. During his arrest, he was too drunk to stand and had the Justice Department’s business card in his hand.

When officers arrived at Ruddy’s home in the suburb of Temple Terrace, they found him hunched over his pickup, holding his keys and using the vehicle for support, the police report said.

The officers noted that he had urinated on himself, was unable to walk unassisted, and failed a sobriety test.

Ruddy has been charged with driving under the influence causing property damage. His blood alcohol level was 0.17%, twice the legal limit. He now faces a maximum of one year in prison.

Despite being indicted, Ruddy stayed on the job for two months and last week represented the United States in court to deliver another victory for the sprawling task force he helped create two decades ago to combat cocaine smuggling at sea.

He is credited with designing Operation Panama Express (PANEX), a task force responsible for more than 90% of the U.S. Coast Guard’s maritime drug interdictions. The average sentence for smugglers caught at sea and prosecuted in Tampa, where Ruddy worked, was longer than any other court in the country.

The accuser was picked up outside his home in Tampa, Florida, with his Department of Justice business card in hand as he hunched over his pickup truck

The lawyer’s blood alcohol level was twice the legal limit and he could barely stand upright. He was also found urinating on himself after hitting a car and leaving the scene

Joseph Ruddy, 59, a prolific federal prosecutor, has been charged with driving under the influence with property damage after he was caught handing police his business card following a July 4 DUI

Ruddy is accused of side-swiping an SUV whose driver had been waiting to turn at a red light, clipping a side mirror and tearing off another piece of the vehicle that was lodged in the fender of Ruddy’s pickup.

“He didn’t even hit the brakes,” a witness told police. ‘He just kept driving and swerved all over the road. I said, “No, he’s going to hurt someone.” So I just followed him until I got the tag number and just called to report it.”

In bodycam footage of the arrest, Tampa Police Officer Taylor Grant is heard telling him, “I understand we might have a better night.”

Before looking at the business card Ruddy is holding in his hand, the officer says, “What are you trying to give me? You realize that when they look at my body-worn camera footage and see this, this is going to end very badly.”

The officer then asks him, “Why didn’t you stop?”

“I didn’t know it was this serious,” Ruddy said indistinctly.

“You hit a vehicle and took off,” the officer said. “You ran away because you were drunk. You probably don’t realize you hit the vehicle.”

Ruddy represented the United States in court for two months after the collision. But he was removed from three cases and removed from the supervisory role a day later the associated press asked the Justice Department about Ruddy’s case.

He is expected to appear in court for his case on September 27.

Ruddy arrived at the United States Courthouse on Friday, September 1. After the collision he stayed at work for two months

Ruddy was removed from three cases and removed from the supervisory role a day after the Associated Press asked the Justice Department about Ruddy’s case.

On Wednesday, a day after the AP asked the Justice Department about Ruddy’s status, the veteran prosecutor was removed from three pending criminal cases.

A Justice Department spokesman would not say whether he was suspended, but said Ruddy had been relieved of his oversight role at the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Tampa while he was still employed. The case has also been referred to the Office of the Inspector General.

Such an inspector general’s investigation would likely focus on whether Ruddy was trying to use his public office for private gain, said Kathleen Clark, a professor of legal ethics at Washington University in St. Louis, who viewed the footage.

“It’s hard to see what this could be other than an attempt to improperly influence the police officer to make things easier for him,” Clark said. “What could be his intention in handing over his business card to the U.S. Attorney’s Office?”

Ruddy designed Operation Panama Express (PANEX), a task force responsible for more than 90% of the U.S. Coast Guard’s naval drug interdictions. The average sentence for smugglers caught at sea and prosecuted in Tampa, where Ruddy worked, was longer than any other court in the country

Ruddy is known in law enforcement circles as one of the architects of Operation Panama Express, or PANEX — a task force created in 2000 to crack down on cocaine trafficking at sea, involving resources from the U.S. Coast Guard, FBI, Drug Enforcement Administration, and Immigration and Immigration were bundled. Customs Enforcement.

Historically, the information generated by PANEX contributes to more than 90% of naval drug prohibitions by the US Coast Guard. Between 2018 and 2022, the Coast Guard removed or destroyed 888 tons of cocaine worth an estimated $26 billion and apprehended 2,776 suspected smugglers, a senior Coast Guard official said in congressional testimony in March. Most of these cases were handled by Ruddy and his colleagues in Tampa, where PANEX is headquartered.

A former Ironman triathlete, Ruddy has a reputation among lawyers for his hard work and toughness in the courtroom. His biggest cases included some of the early renditions from Colombia of top smugglers to the feared Cali cartel.

But most of the cases handled outside his office mainly involve poor fishermen from Central and South America, who are the lowest rungs of the drug trade. Often the drugs don’t even make their way to US shores and the constitutional guarantees of due process that normally apply in US criminal cases are only loosely adhered to.

“Ruddy is at the heart of a costly and aggressive prosecutor-led dragnet that extracts hundreds of low-level cocaine traffickers from the oceans each year and locks them up in the U.S.,” said Kendra McSweeney, an Ohio State University geographer who is part of a team studying maritime interdiction policy.

Research from the Ohio State Interdiction Lab found that between 2014 and 2020, the average sentence for smugglers caught at sea and prosecuted in Tampa was 10 years – longer than any other court in the country, and compared to seven years and six months in Miami, which handles the second largest number of such cases.

Last Friday, nearly two months after his arrest, Ruddy was in court to uphold a settlement in the case of a Brazilian man, Flavio Fontes Pereira, who was found by the US Coast Guard in February with more than 3.3 tons cocaine aboard a sailboat off the coast of Guinea, in West Africa.

After two weeks aboard the U.S. Coast Guard ship, Pereira made his first court appearance in Tampa in March, charged under the Maritime Drug Law Enforcement Act, which gives the U.S. unique arrest powers anywhere on high seas when it is determined that a ship is ‘without’. nationality.’