Seventh person with HIV is CURED after stem cell transplant for leukemia, scientists claim

A 60-year-old German man has likely been “cured” of HIV, a medical milestone that only six other people have achieved, doctors say.

The man was being treated for acute myeloid leukemia, a form of blood cancer that begins in young white blood cells in the bone marrow, with a stem cell transplant.

The painful and risky procedure is intended for people who have both HIV and aggressive leukemia, so it’s not an option for most of the nearly 40 million people worldwide living with the deadly virus.

According to doctors, he now appears to be cancer and HIV free.

The German, who wishes to remain anonymous, was dubbed the “next Berlin patient”.

Timothy Ray Brown with his dog Jack on Treasure Island in San Francisco in 2011. Brown, known for years as the Berlin Patient, received a transplant in Germany from a donor with natural resistance to the AIDS virus. It was thought to have cured Brown’s leukemia and HIV

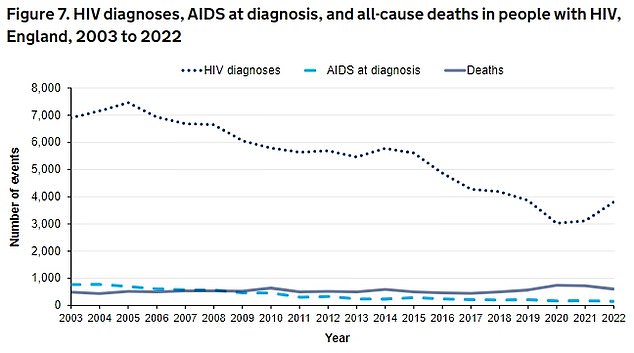

The latest UKHSA data shows the number of HIV diagnoses has increased by 22 per cent – from 3,118 in 2021 to 3,805 in 2022.

The original Berlin patient, Timothy Ray Brown, was the first person to be declared cured of HIV in 2008. Brown died of cancer in 2020.

The second man from Berlin to achieve long-term HIV remission was announced ahead of the 25th International AIDS Conference to be held next week in the German city of Munich.

He was first diagnosed with HIV in 2009, according to the research abstract presented at the conference.

The man received a bone marrow transplant for his leukemia in 2015. The procedure, which has a 10 percent chance of death, essentially replaces a person’s immune system.

In late 2018, he stopped taking antiretroviral drugs, which reduce the amount of HIV in the blood.

Nearly six years later, he appears to be free of both HIV and cancer, medical researchers said.

Christian Gaebler, a physician-researcher at Berlin’s Charite University Hospital who is treating the patient, said the team cannot be “absolutely certain” that every trace of HIV has been eradicated.

But “the patient’s case strongly suggests a cure for HIV,” Gaebler added.

“He is feeling good and is enthusiastic about contributing to our research.”

According to the National AIDS Trust, an estimated 105,200 people are living with HIV in the UK.

But only 94 percent of these people are diagnosed.

This means that around 1 in 16 people with HIV in the UK do not know they have the virus.

Sharon Lewin, president of the International AIDS Society, said researchers are hesitant to use the word “cure” because it’s not clear how long they would need to follow such cases.

But more than five years in remission means the man could be “close” to recovery, she told a news conference.

There is an important difference between the man’s case and other HIV patients who have achieved long-term remission, she said.

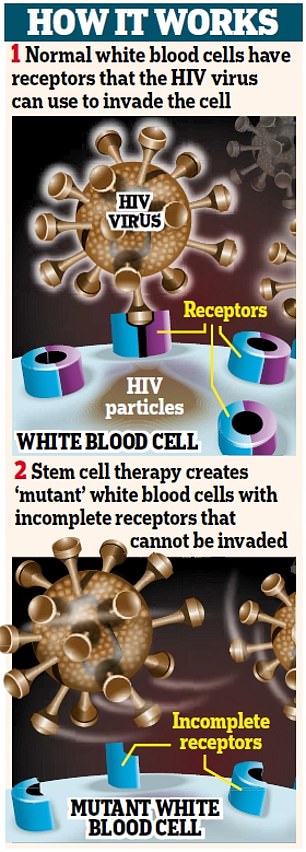

All but one of the patients received stem cells from donors with a rare mutation missing part of the CCR5 gene, which prevented HIV from entering their body cells.

These donors had inherited two copies of the mutated CCR5 gene, one from each parent, making them “essentially immune” to HIV, Lewin said.

But the new patient from Berlin is the first to receive stem cells from a donor who inherited only one copy of the mutated gene.

About 15 percent of people of European descent have one mutated copy, compared to one percent for both.

According to the National AIDS Trust (NIT), there are an estimated 105,200 people living with HIV in the UK.

Timothy Ray Brown poses for a photo, Monday, March 4, 2019, in Seattle. Brown, also known as the “Berlin Patient,” was the first person to be cured of HIV infection

Researchers hope this latest success means there will be a much larger potential pool of donors in the future.

The new case also holds “great promise” for the broader search for an HIV drug that works for all patients, Lewin said.

“This is because it suggests that it is not necessary to remove every bit of CCR5 for gene therapy to work,” she added.

The Geneva patient, whose case was announced at last year’s AIDS conference, is the other outlier among the seven. He received a transplant from a donor without CCR5 mutations — and still achieved long-term remission.

This showed that the effectiveness of the procedure did not depend solely on the CCR5 gene, Lewin said.

Mr. Brown, the first patient to be “cured,” was diagnosed with HIV in 1995 while studying in Berlin.

Ten years later, he was diagnosed with leukemia, a form of cancer that affects the blood and bone marrow.

Acute myeloid leukemia is the most common form in adults, with about 3,000 Britons and 20,000 Americans diagnosed each year.

It is also the deadliest disease, killing 2,700 people each year in the UK and 11,000 in the US.

To treat his leukemia, his doctor at the Free University of Berlin used a stem cell transplant from a donor who had a rare genetic mutation that gave him natural resistance to HIV. He hoped this would eradicate both diseases.

It took two painful and dangerous procedures, but it was a success: in 2008, Brown was declared free of the two conditions and was initially referred to at a medical conference as “the Berlin patient” to preserve his anonymity.

Two years later, he decided to break his silence and became a public figure, giving speeches and interviews and setting up his own foundation.

“I am living proof that there is a cure for AIDS,” he told AFP in 2012. “It is truly wonderful to be cured of HIV.”

Although he remained cured of HIV, his cancer returned.

Ten years after Brown was cured, a second HIV patient, nicknamed “the London patient,” went into remission 19 months after a similar procedure.

The patient, Adam Castillejo, is currently HIV-free.

Other patients include a patient from Düsseldorf in 2023, a patient from New York in 2022, the patient from Esperanza in 2021 and Loreen Willenberg in 2020.

Unlike the other patients, the Esperanza patient and Mrs. Willenberg’s immune systems naturally clear the virus from their bodies.