Scientists warn Great Barrier Reef could disappear in next 30 years after making startling discovery

Scientists are sounding the alarm about the demise of the Great Barrier Reef after discovering a starling.

They found that ocean temperatures around this natural wonder are now the highest in at least 400 years, 0.34 degrees Fahrenheit above the previous record.

Researchers warn that if warming continues, the iconic ecosystem could disappear within 30 years.

The findings were made by drilling coral cores to identify geochemical changes and reconstruct past sea surface temperatures.

Aerial photo shows bleached and dead coral around Lizard Island on the Great Barrier Reef, April 4, 2024. Researchers warned that if warming continues, the iconic ecosystem could disappear in the next 30 years.

“If humanity does not deviate from its current course, our generation is likely to witness the demise of one of Earth’s great natural wonders,” wrote Benjamin Henley, lead author of the study from the University of Melbourne, for The conversation.

The research team, which includes several Australian universities, analysed long-lived corals in and around the reef.

These corals keep records of ocean temperatures in their skeletons. The researchers used these records to reconstruct sea surface temperatures from 1618 to 1995, as well as modern sea surface temperature measurements from 1900 to 2024.

Co-author Helen McGregor said it was similar to counting the rings of a tree to determine its age.

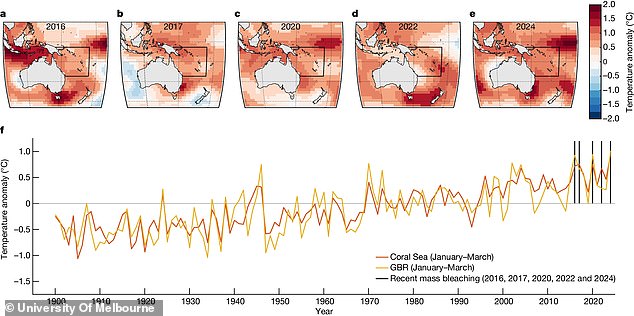

Their research showed that sea surface temperatures in the Coral Sea had been relatively stable and cool for centuries, but between January and March they rose rapidly to unprecedented levels, posing a threat to the reef.

The analysis found that ocean temperatures around the reef have risen significantly since 1960, with five of the six warmest years on record occurring in the past decade.

“From 1960 to 2024, we saw an average annual summer warming of 0.216F per decade,” researchers told The Conversation.

They found that ocean temperatures around the natural wonder are now the highest in at least 400 years, 0.34 degrees Fahrenheit above the previous record high.

The research team drilled cores of coral skeletons on the Great Barrier Reef to collect climate data.

The researchers linked this temperature increase to human-induced climate change.

“Right now the Great Barrier Reef is in danger,” Henley told DailyMail.com.

‘There is a high probability that serious mass bleaching events will occur in the coming years.’

Scientists have long said that coral loss is likely to be a result of future warming as the world approaches the 2.7 degree Fahrenheit limit set by the 2015 Paris climate agreement, which countries have agreed to keep warming below.

Even if global warming remains within the Paris Agreement target (and scientists say the Earth is almost certain to meet that target), 70 to 90 percent of the world’s corals could be threatened, the study authors said.

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is the largest coral reef system in the world, covering 133,000 square miles—an area larger than the size of Italy—off the coast of Queensland. It is so large that it is visible from space.

The Great Barrier Reef attracts more than two million tourists each year.

Rising ocean temperatures are causing mass coral bleaching in the Great Barrier Reef

This biodiversity hotspot is home to more than 9,000 known species, including 400 species of coral, 1,500 species of fish and 4,000 species of mollusks.

It also supports tourism, fishing and other commercial industries. The total economic value of the reef is estimated at $56 billion and it supports approximately 64,000 jobs.

But that could change quickly, scientists warn.

When ocean temperatures rise too high, corals expel the algae that live in their tissues.

This process, also known as coral bleaching, causes corals to turn completely white, depriving them of their main food source and making them more vulnerable to disease.

Corals can survive bleaching, but they need time to recover, Henley said. He worries that the frequency of mass bleaching events could increase as ocean temperatures continue to rise.

Even if there is only one mass coral bleaching event per year, it becomes extremely difficult for corals to recover, putting them at greater risk of dying.

This summer, the Great Barrier Reef experienced its largest and most extreme mass bleaching event ever recorded, scientists from the Australian Institute of Marine Science reported in a separate report published this week.

It was the fifth time in just eight years that the reef suffered mass bleaching.

This study provides a new perspective on how rising ocean temperatures have affected the Great Barrier Reef over the long term and how they will continue to affect the reef in the future, Henley said.

As climate change continues, its impact on the Great Barrier Reef will be felt on both local and international scales, and in terms of both environmental and economic consequences.

“It’s a place of spectacular beauty and ecologically unique,” Henley said, adding: “It’s a very special place, and we’re losing it.”