Scientists revive a pig’s brain almost an HOUR after it died – and they say the same technique could be used in humans

It may sound like something straight out of Frankenstein’s laboratory.

But Chinese researchers have now managed to revive a pig’s brain an hour after it was removed from the body.

Scientists from the Guangdong Provincial International Cooperation Base of Science and Technology have managed to restore brain waves in the brain of a dead pig that are “considered conscious activity” using an unusual new method.

The technique works by incorporating a healthy liver into the artificial life support system that keeps the brain alive.

It is believed that the liver produces reserve energy molecules called ‘ketone bodies’ that protect the brain from injury.

Although the technique has only been used in pigs so far, the researchers say it could be used in humans in the near future.

The researchers suggest that heart attack patients could be resuscitated by connecting them to gene-edited pig livers.

A team of Chinese scientists has managed to revive a pig’s brain up to an hour after it was removed from the body using a new life support technique (stock image)

When the body goes into cardiac arrest and the heart stops beating, one of the most damaging things that can happen is that the organs run out of oxygen and energy.

If there is no blood circulation, the cells that make up important tissues soon begin to die.

This process, called ischemia, can cause irreversible brain damage within minutes, leading to lifelong health complications or death.

However, when they looked at hospital records for cardiac arrest patients, the researchers noticed a surprising pattern.

Patients who also suffered from liver ischemia tended to experience worse neurological damage, stayed longer in intensive care, and had higher mortality rates.

In contrast, those whose livers remained healthy survived much longer and had better health outcomes.

From this, the researchers hypothesize that there may be a link between the function of the liver and the way the brain responds to cardiac arrest.

To test this theory, the researchers artificially induced ischemia in 17 laboratory-raised Tibetan mini-pigs.

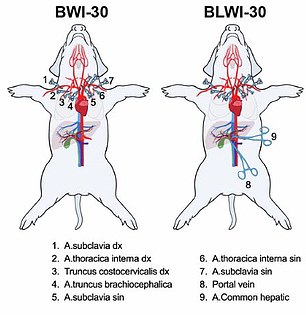

The researchers theorized that the liver was somehow connected to the brain during cardiac arrest. They found that Tibetan mini pigs (pictured) suffered less brain damage during a simulated heart attack if the liver was left intact (pictured right)

One group had blood flow restricted only to the brain, a second also had circulation cut off to the liver, while a third remained the control group.

When the pigs’ brains were removed and dissected, the researchers found that those who had not had liver ischemia suffered significantly less brain damage.

Putting these ideas into practice, the researchers aimed to develop a life support system that could include a healthy liver.

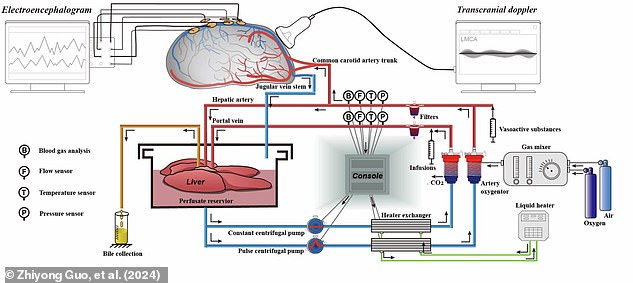

Typically, a basic life support system consists of an artificial heart and lungs and is used to pump fresh oxygenated blood to the brain.

This technique, called extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, bypasses the role of the heart and can keep a patient’s brain alive until normal heart activity is restored.

However, in the researchers’ modified version, a living liver was added to this circuit so that fresh blood was pumped through the organ before reaching the brain.

The pig brains were then removed and connected to the basic life support system or to the modified version including a liver.

First, the brain was left alone for ten minutes before life support was turned on – to simulate a major heart attack.

The brain was revived using a modified life support system (pictured), which includes an artificial heart and lungs in addition to a living, healthy liver. This system was able to make a pig’s brain function ‘consciously’ again for up to six hours, even after it had been dead for 50 minutes

In the system without liver, brain activity returned within half an hour and continued for three to four hours.

In brains connected to the liver, brain activity restarted within an hour, but lasted the entire six-hour observation period.

To boost this even further, the researchers then began to extend how long the brain was active before life support was turned on.

They found that the longest interval that showed serious promise of coming back to life was 50 minutes.

Brains that remained detached from the body during this time still produced alpha and beta waves, indicating conscious activity, for the full six hours after being revived.

Even brains that had been dormant for a full hour could be coaxed back into conscious activity, but this quickly disappeared after three hours.

While removing the brain clearly wouldn’t work for human patients, the researchers say these findings could help save lives.

By incorporating a healthy liver into the life-sustaining process, doctors may be able to extend the period in which patients can be revived.

The researchers say this technique could be used to increase the period over which human patients can be resuscitated. In the future, cardiac arrest patients could be connected to livers from ‘gene-edited mini pigs’ (stock image)

This can be done using an artificial liver or by connecting the patient to another healthy liver.

The researchers even note that recent developments in ‘gene-engineered mini-pigs’ could provide a ‘timely organ supply’ for this treatment.

In their article, published in EMBO Molecular Medicine, Dr. Zhiyong Guo, from Sun-Yat-Sen University, and his co-authors: ‘These findings highlight potential therapeutic targets for intervention.’