Scientists reveal the TRUE face of Santa Claus for the first time in almost 1,700 years

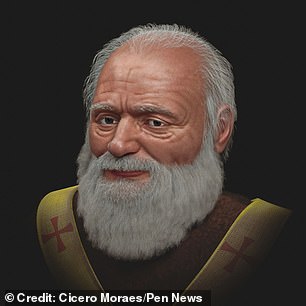

The true face of the man who inspired Santa Claus has been seen for the first time in almost 1,700 years after scientists reconstructed his image from his skull.

Sinterklaas of Myra was an early Christian saint whose reputation for gift-giving inspired the Dutch folk figure Sinterklaas, who would later become Santa Claus in the US.

This mythical figure would then merge with the English Santa Claus – often associated with parties and games, rather than gifts – to create the character that children love today.

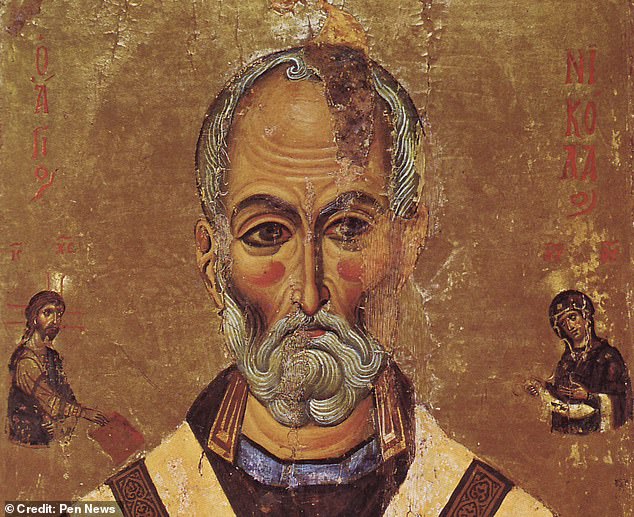

Yet no image of the man behind the myth has survived during his lifetime, with most images of ‘Old Saint Nick’ dating from centuries after his death in 343 AD.

Now his living face can be seen for the first time since the time of the late Roman Empire, after experts forensically reconstructed his facial features using his skull.

Mr Moraes, lead author of the new study, said it was a “strong and gentle sight”.

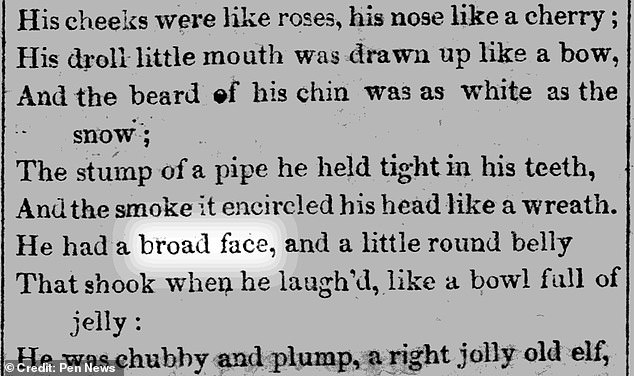

He said it was also ‘curiously compatible’ with the ‘broad face’ described in the 1823 poem A Visit From St Nicholas, commonly known as ‘Twas The Night Before Christmas’.

He said: ‘The skull has a very robust appearance and generates a strong face, because its dimensions on the horizontal axis are larger than average.

The true face of the man who inspired Santa Claus has been seen for the first time in almost 1,700 years after scientists reconstructed his likeness from his skull

Sinterklaas of Myra was an early Christian saint whose reputation for gift-giving inspired the Dutch folk figure Sinterklaas, who would later become Santa Claus in the US (stock image)

‘This resulted in a ‘broad face’ that was strangely compatible with the 1823 poem.

“This feature, combined with a thick beard, is very reminiscent of the figure we have in mind when we think of Santa Claus.”

José Luís Lira, co-author of Moraes and expert on hagiographies, described the significance of the real Nicholas of Myra.

He said: ‘He was a bishop who lived in the early centuries of Christianity and had the courage to defend and live the teachings of Jesus Christ, even at the risk of his life.

‘He challenged the authorities, including the Roman emperor, for this choice.

‘He helped those in need so often and effectively that when people were looking for a symbol of kindness for Christmas, the inspiration came from him.

“His memory is universal, not only among Christians, but among all peoples.”

Mr. Moraes explained how the famous saint became today’s popular legend.

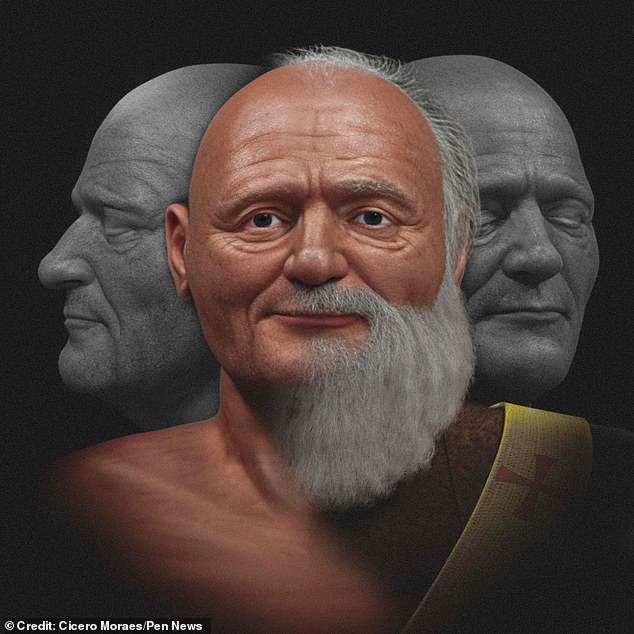

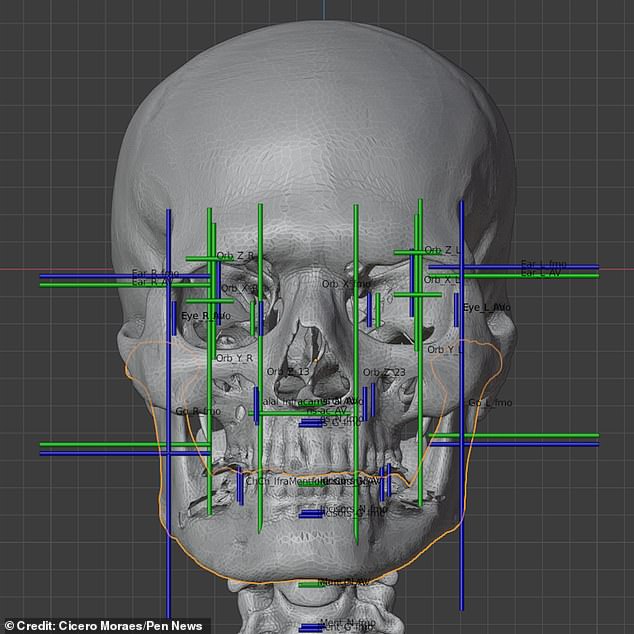

To create the face, Mr. Moraes and his team used data collected by Luigi Martino in the 1950s, with permission from the Centro Studi Nicolaiani.

Mr Moraes said: ‘We initially reconstructed the skull in 3D using this data. We then tracked the profile of the face using statistical projections’

He said: ‘The Protestant Reformation, led by Martin Luther, was a movement that contributed to the disappearance of devotion to Saint Nicholas in many countries.

‘A notable exception was in the Netherlands, where the legend of Sinterklaas – a linguistic suppression of the saint’s name – remained strong and even influenced that country’s colonies.

‘One of these colonies was the city of New Amsterdam, now New York, where the legend was anglicized into the name Santa Claus.

‘He was described as an old man who punished misbehaving children and rewarded those who behaved well with gifts.’

He continued, “The image of Santa Claus as we know it today is based on an illustration by Thomas Nast for Harper’s Weekly magazine in early 1863.

‘This in turn was inspired by the description in the 1823 poem A Visit from St. Nicholas, attributed to Clement Clarke Moore.’

The poem gave rise to many popular conceptions of the folk figure we have today, including his rosy cheeks, his reindeer, his sleigh, his bag of toys, and the “broad face” described earlier.

To create the face, Mr. Moraes and his team used data collected in the 1950s by Luigi Martino, with permission from the Centro Studi Nicolaiani.

This image shows a 13th century depiction of Saint Nicholas from St. Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai, Egypt

The face is ‘curiously compatible’ with the ‘broad face’ described in the 1823 poem, A Visit From St Nicholas, commonly known as ‘Twas The Night Before Christmas’.

He said: ‘We initially reconstructed the skull in 3D using this data.

‘We then tracked the profile of the face using statistical projections.

‘We have supplemented this with the anatomical deformation technique, in which the tomography of the head of a living person is adjusted so that the skull of the virtual donor matches that of the saint.

‘The final face is an interpolation of all this information, looking for anatomical and statistical coherence.’

The result is two series of images: one objective in grayscale and one more artistic – with the addition of features such as a beard and clothing, inspired by the iconography of Sinterklaas.

However, the saint’s remains reveal more than just his face.

Mr Moraes said: ‘He apparently suffered from severe chronic arthritis in his spine and pelvis, and his skull had bone thickening which could cause frequent headaches.

“According to this source, his diet would be largely plant-based.”

During his lifetime, Saint Nicholas was bishop of Myra, in what is now Turkey.

Several deeds are attributed to him, including rescuing three girls from prostitution by paying a dowry for each, allowing them to marry.

He is also said to have resurrected three children murdered by a butcher, who had brined them and planned to sell them as pork.

Initially buried in Myra, his bones were later transferred to Bari in Italy, where they remain today.

Mr Moraes, Dr Lira and their co-author, Thiago Beaini, published their research in the journal OrtogOnLineMag.