Scientists reveal face of ‘completely unknown’ human ancestor that is rewriting the history of our evolution

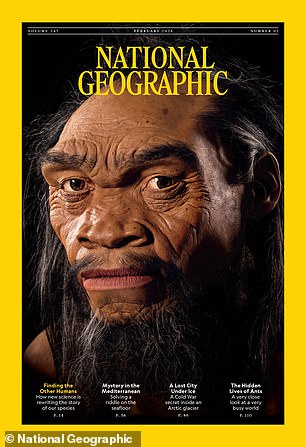

Scientists have reconstructed the face of a long-lost human ancestor who may have played a crucial role in our evolution.

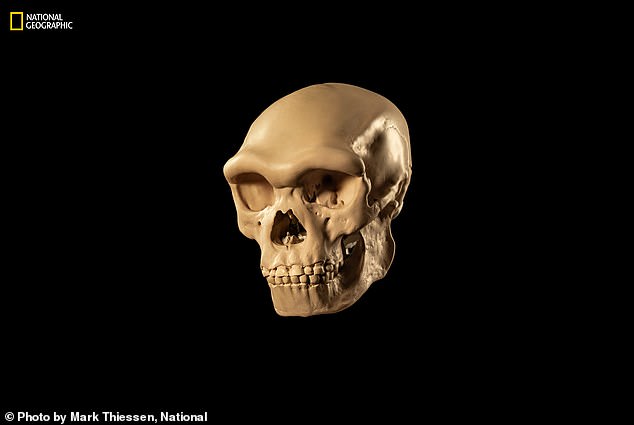

They used the Harbin skull, also known as “Dragon Man,” a 150,000-year-old, nearly complete human skull discovered in China in 1933.

Paleoartist John Gurche used fossils and genetic data from the extinct species to recreate plastic replicas of remains.

He estimated the ancient hominid’s facial features using the eye-to-socket size ratio shared between African apes and modern humans, and by measuring aspects of the skull’s bone structure to determine the shape and size of the nose.

Gurche then put muscles on the face by tracing the marks on the skull left behind when chewing, revealing the first real look at an “unknown human.”

The species, named ‘Denisovans’ after a cave where some of their remains were found, lived between 200,000 and 25,000 years ago.

Their fossil and DNA records show that they lived on the Tibetan plateau but traveled far and wide, with traces of their presence found in Southeast Asia, Siberia and Oceania.

Scientists sequenced their genetic code for the first time in 2010 using a 60,000-year-old finger bone recovered from the Denisova Cave in Siberia, finding Denisovan DNA in modern humans around the world and especially in the populations of Papua -New Guinea.

Scientists have reconstructed the face of a long-lost human ancestor who may have played a crucial role in our evolution

This is strong evidence suggesting that Denisovans interbred with Homo sapiens before disappearing. Besides Neanderthals, these ancient humans are our closest extinct relatives.

Researchers believe this interbreeding helped Homo sapiens adapt to new environments as they expanded their range around the world, playing an important role in our evolutionary history.

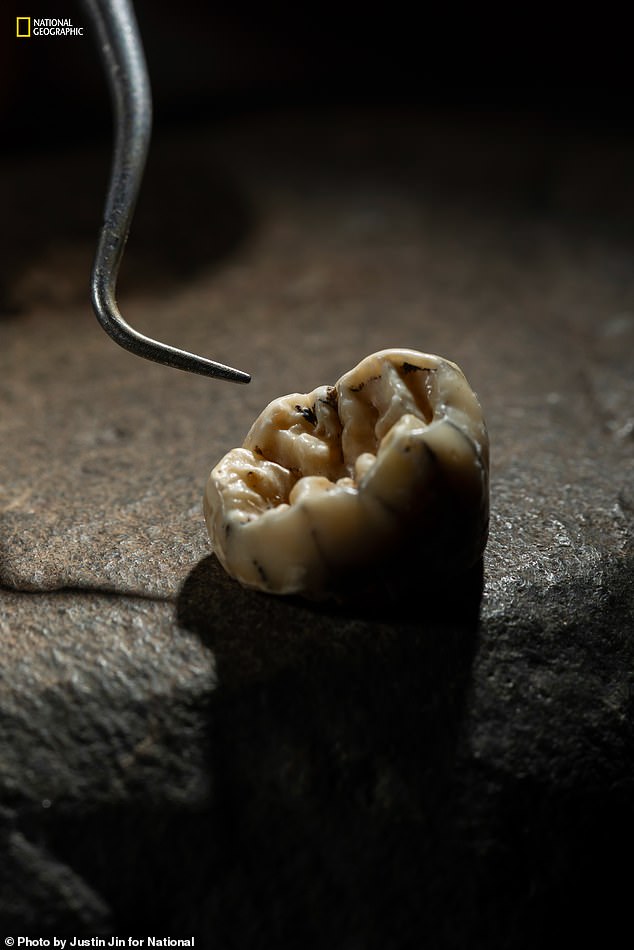

Despite a flurry of research in the past two decades, much is still unknown about these early humans, as their fossil record is incredibly sparse compared to that of Neanderthals.

But thanks to a skull hidden for more than 80 years in northeastern China, we can now see what our Denisovan ancestors really looked like.

The skull was found in 1933 by a worker in Harbin, China. Although similar in size to a modern human skull, it has a wider mouth and a more prominent forehead.

When he discovered the remarkably complete, 150,000-year-old fossil, he hid it in a pit where it remained for the rest of the 20th century.

In 2018, the skull resurfaced when the Chinese worker told his grandson about it shortly before his death.

Today this fossil is known as the Harbin skull.

But there is a strong possibility that the Harbin skull is Denisovan, researchers say. A paleoartist used a plastic replica of this skull to reconstruct the Denisovan’s face

The main evidence supporting the Denisovan descent of the Harbin skull is the morphological similarity between the skull and a jawbone found in Xiahe Cave on the Tibetan Plateau in 1980.

Gurche used this skull to create a lifelike reconstruction of the Denisovan face.

Paleoartists use fossils and genetic data to determine what ancient species looked like when they were alive, and then create models or illustrations of their appearance.

Gurche is known for his hyper-realistic sculptures. His goal is always to get as close as possible to “looking into the eyes of these extinct species,” he told National Geographic.

He used a plastic replica of the Harbin skull, commissioned by National Geographic, to create his Denisovan model.

Next, Gurche estimated the size of the Denisovan’s eyes using comparative anatomy, which is the process of comparing and contrasting the anatomy of different species.

He knew that African apes and humans share a similar ratio of eyeball diameter to eye socket size, so he used this ratio to shape the eyes.

As for the nose, Gurche carefully studied and measured the bone structure of the Harbin skull to deduce how wide the nasal cartilage could have been and how far the nose extended from the face.

Many other fossils of the Denisovan lineage have been recovered around the world, including this molar found in Laos. But compared to Neanderthals, Denisovan fossils are scarce

All human skulls have markings that indicate the position of the masseter muscles on the sides of the head, so he used these in addition to other measurements that indicate their thickness to build out the Denisovan’s facial shape.

Denisovan’s facial reconstruction is featured on the February 2025 cover of National Geographic

The end result is a lifelike, scientifically based representation of the appearance of this ancient human, offering the most realistic look at our Denisovan’s ancestors to date.

For more information about this story, visit Natgeo.com.

Today, the lineage of the Harbin skull is still debated, as there is no definitive genetic evidence to confirm which species it belongs to.

But experts believe there is a good chance the skull is Denisovan.

The main evidence supporting this is the morphological similarity between the Harbin skull and a jawbone, found in the Xiahe Cave on the Tibetan Plateau in 1980.

Although the 160,000-year-old jawbone found 45 years ago contained no viable traces of genetic material, scientists in 2016 were able to identify its lineage using a new technique that indirectly analyzes a fossil’s DNA through its more durable proteins.

To unravel exactly how the Denisovans were able to travel thousands of kilometers around the world, and why they disappeared, more fossils are needed.

That analysis showed that the jawbone was Denisovan’s, and its similarity to the Harbin skull suggests that is likely the case.

Furthermore, the skull was found within the known geographic range of the Denisovans, and was dated to a similar age.

Based on this evidence, some experts believe that the Harbin skull is the most complete Denisovan fossil ever found.

While this new look at the Denisovan face represents a major step forward in scientists’ understanding of this extinct human species, unraveling how exactly they were able to travel thousands of miles around the world, and why they disappeared, will require more fossils.