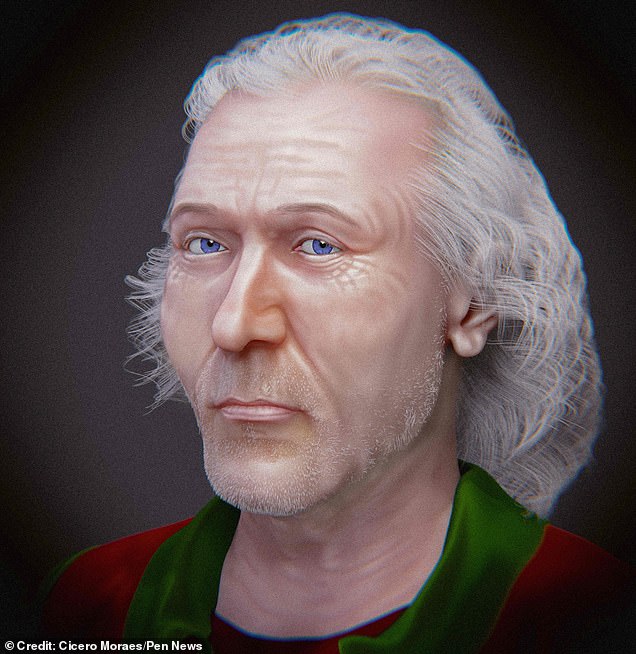

Scientists reconstruct the face of Copernicus – the astronomer who proposed that the planets revolve around the sun – for the first time in more than 400 years

His theories may have revolutionized the way we think about the world, but Copernicus’ face has since been lost to time.

Nicolaus Copernicus, a Polish astronomer born in 1473, revolutionized the study of the planets by suggesting that the Earth revolved around the sun.

Not a single painting of the famous scientist was made during his lifetime; his only self-portrait was destroyed in a fire in 1597.

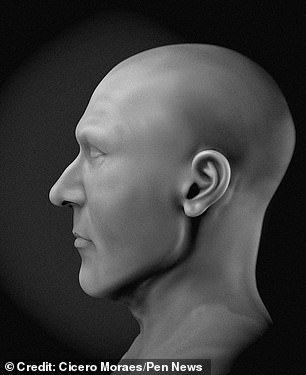

Now scientists have reconstructed Copernicus’ face, more than 400 years after it was last seen.

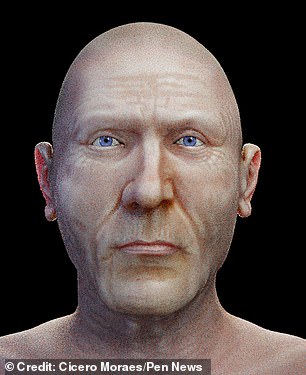

These incredible images give us a glimpse of a ‘serene’ face showing the astronomer as he would have looked at the time of his death, at the age of 70 in 1543.

More than 400 years after his death, scientists have reconstructed the face of Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, who proposed the idea that the planets revolve around the sun.

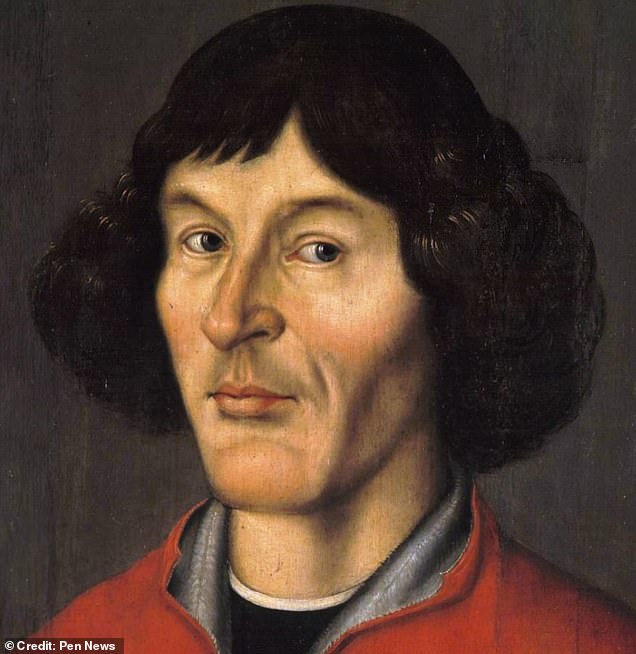

All surviving portraits of Copernicus, such as this one from the 18th century, were made after his death and were based on a single, now destroyed self-portrait

The face of Copernicus is one of the enduring mysteries in the history of science.

The visionary scientist was the first to propose the ‘heliocentric’ model of the solar system, which placed the sun at the center of the solar system.

His theories contradicted the official position of the Catholic Church and his works were banned after his death.

Despite his fame, all surviving portraits of Copernicus were made after his death and were based on a single self-portrait that was long since destroyed.

This means that despite being the cornerstone of modern astronomy, no one could be sure if it really looked like these paintings.

Cicero Moraes, author of the new study, said: ‘A problem with historical figures is whether the portraits that survive to this day are compatible with the individual in life.

“In the case of Copernicus, as far as I have studied, there is no intact portrait painted during his lifetime.”

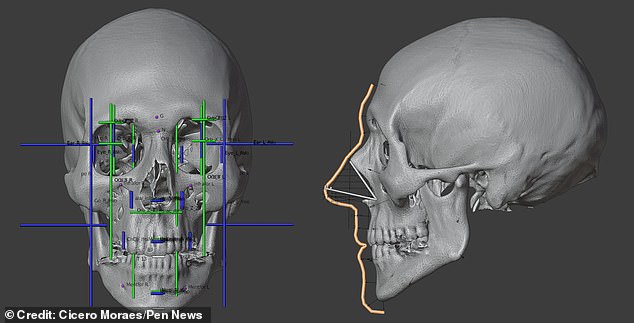

To bring this 400-year-old mystery to an end, Mr. Moraes digitally reconstructed a face based on what is believed to be Copernicus’ skull.

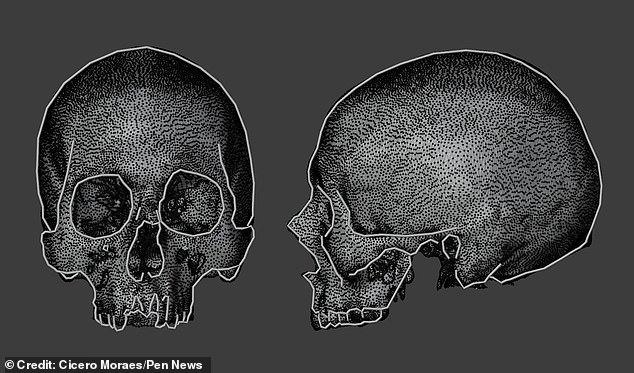

These remains were discovered in 2005 beneath Frombork Cathedral in Poland, where Copernicus lived, worked and died.

Because the jaw was missing, Mr. Moraes first used computed tomography data to reconstruct what the entire skull would have looked like.

Mr Moraes said: ‘Once I had reconstructed the entire skull, I moved on to the facial approach.

‘This consisted of using data from measurements on living individuals to arrive at a face that could be compatible with the machined skull.’

This is a scan of the skull believed to have belonged to Copernicus and from which the reconstruction was made

Because the skull was missing a jaw, study author Cicero Moraes first had to digitally reconstruct what it would have looked like based on the existing remains

Using the skull as a basis, Mr. Moraes used measurements of living individuals to approximate what the original face might have looked like

Moraes’ reconstruction revealed a face remarkably similar to surviving portraits of Copernicus.

The digital reconstruction in particular matches one of Copernicus’ most famous posthumous portraits almost perfectly.

For comparison, you can see how both the portrait and the reconstruction share a similar square jaw, high cheekbones, and a similar nose.

However, these incredible images can solve two mysteries at the same time.

While the archaeologists who discovered the skull were “almost 100 percent” certain that it belonged to Copernicus, others were not so sure.

Supporters point to the fact that hairs from a book believed to be by Copernicus turned out to be a DNA match with the remains.

However, the origin of the skull is disputed. Some experts have wondered if it really belonged to the famous scientist.

The similarity between the reconstruction (left) and the most famous surviving portrait (right) suggests that the portraits are accurate and that this skull was indeed Copernicus’s.

This photo shows the shape of the reconstruction overlaid on a famous posthumous portrait, showing that they are a close match

Now Mr Moraes, an expert in forensic reconstruction, says his reconstructions could help settle the debate.

He says: ‘I was very interested in the debate surrounding the discovery of the remains attributed to Copernicus.’

The close similarity between the reconstruction of the skull and the portraits could be explained by the fact that the portraits are accurate and the skull is actually that of Copernicus.

In turn, Mr. Moraes downplays some of the scientific significance of this discovery.

He concludes: ‘The reconstruction was largely similar to the most famous portrait of the astronomer painted around 1580.

‘This proves nothing, but it is a fact that they look alike; It could just be a coincidence, but it happened.”